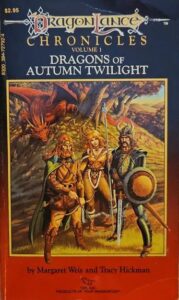

Author: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman

Published: November 1984

To be perfectly honest, I’m approaching this book with some trepidation. I think I first read it as a pre-teen, and I remember enjoying the hell out of it — but then, I enjoyed just about everything I read back then because everything was new and I had no filters for taste or quality. Having not read it for a few decades, my hazy recollections are of a handful of great scenes interspersed with… uhh… some stuff I barely recall and thus was probably fairly forgettable. Will this be an enjoyable nostalgia trip, or a painful re-evaluation of my childhood memories?

I’m especially nervous about it because of the difficult circumstances under which this novel was written. First of all, Weis and Hickman had only three months to finish the manuscript, and Hickman was doing it in his spare time while also working on the Dragonlance D&D module series. Any author would struggle to produce something readable in that scenario! But even worse, instead of coming up with their own story that would do an optimal job of introducing their new world and showcasing the best bits, they were stuck adapting the first two D&D modules, Dragons of Despair and Dragons of Flame. This meant that not only did they have less control over the novel’s pacing, but they had to include the modules’ long dungeon crawl segments, and dungeon crawls are extremely hard to render well in prose. (They tend to be long, overly detailed, and padded with random encounters, so the plot grinds to a halt until the dungeon’s climax.) Even the structure of this novel reflects the modules’ influence; it’s broken up into “Book I” and “Book II,” which correspond to the events of each module.

Given that the Dragonlance Chronicles trilogy is is probably the most culturally pervasive product TSR ever released aside from Dungeons & Dragons itself, I’m going to spend more time than usual on this review and dig into things in a fairly detailed fashion. Buckle up!

Plot

The plot here is mostly based on the D&D modules, but some of the characters and events come from a D&D campaign Hickman ran with some of his TSR colleagues to playtest the Dragonlance material. There’s little point in trying to tease out which bits happened during play and which were invented by the authors; it was a very long time ago, and even the people who were there have probably forgotten most of the details. I’ll just take the story as written and try not to dig into the meta-level of how it came to be, because in the end that’s merely mildly interesting trivia. (In fact, I’ve avoided digging into the details of the D&D modules so that they wouldn’t influence my impressions of the novel’s plot.)

This story begins, as classic D&D stories often do, with the heroes meeting in a tavern. I don’t think it was as much of a cliché back then, mind you, but it’s funny in retrospect. And it’s certainly more picturesque than your usual tavern — like all the other buildings in town, it’s a treehouse forty feet up a gigantic tree. I’m struggling to imagine how such a village would form under real-world conditions. The amount of extra labour involved in getting food, firewood, and people up the trees and garbage and people down is staggering, and it’s not fortified in a way that would give you significant defensive advantages. You still need to do all of the food-growing and production of textile raw materials (the majority of labour in a pre-industrial society) on the ground, so most of your time would be spent down there anyhow, and you’d need to store what you grow down there because storing tons of grain up a tree is non-trivially hard. So your homes are somewhat protected from raiders, but they can still take all your food and everyone dies of starvation. God, I need to stop over-analyzing things.

Still, points for originality… or semi-originality, anyhow, since the whole “tree city” thing is one of a few aspects of this book borrowed from Tolkien with just enough changes to make them not plagiarism. More on that later.

Anyhow, the characters are all meeting up again after five years spent individually wandering, a period of time which will soon be covered by innumerable prequels of declining quality. (Funny how Sturm doesn’t mention that he flew to the fucking moon…) It’s a good setup; when most of the party are old friends who know each other well, you can dispense with lots of awkward “meeting each other” and “bringing the group together” scenes.

An old man who is very heavy-handedly hinted to be a god in disguise railroads them into the plot with all of the subtlety of a frustrated Dungeon Master. This is going to be a continual problem throughout this book, to the point where you could make it a drinking game — take a shot every time divine intervention drives the plot, then see if you can still stand up afterwards. (Take the first shot now.) Before long I was baffled by why the gods bothered with all this subterfuge and leading humans around by the nose. Why not just show up in front of these people, say “Hey, I’m a god and I need your help,” and tell them what’s going on? They’ll be willing to believe after a little miracle or two — they’ve spent the past five years looking for exactly that kind of evidence. But no, instead the gods are all “let’s push them in the direction of the plot and let them stumble around and fuck up a lot.” Sigh.

That said, the whole sequence between the inn and the boat does a good job of demonstrating how the characters are capable adventurers who work well as a team. Divine intervention prevents them from holing up until the trouble is all over (drink!), so they run away. There follows an interminable sequence where it takes them nearly an entire chapter just to get into a boat, in a sequence that’s uncannily like watching a group of D&D players sitting around a table arguing about what to do. The plot screeches to a halt while they argue, which is good for characterization but pretty awful for the tense chase scene we’re supposed to be having.

Later they get their first real fight scene against a group of draconians (the lizard-people soldiers of Takhisis, the Queen of Darkness), and it’s… not my favourite. They get some useful information and character development out of it, but the actual writing of the fight scene feels very much like someone giving a round-by-round description of each character’s actions in a D&D combat, such that you can almost hear the dice rolling in the background. This will be a running issue throughout the entire book.

The gods send them a vision that leads them out of danger (drink!) and into the Forest of Tolkien Tropes. First they meet a troupe of undead warriors who are cursed to hang around until they fulfill a broken pledge, and then they meet a powerful but friendly divine being who rescues them from the dangerous forest and gives them food, rest, and comfort. The Forestmaster then tells them where to go next and gives them transportation there. (Drink!) And then there are some centaurs who…

“Thee must come with us,” the centaur ordered.

Sweet Jesus, not again! All the centaurs talk like Ren Faire staff — they just replace every single pronoun with “thee” regardless of whether it makes the slightest grammatical sense, over and over again. It seems like not a single TSR editor on either the Dragonlance or Forgotten Realms lines knew how English used to work. Sorry — it’s a real pet peeve of mine. Meanwhile, the Forestmaster is busy driving foreshadowing into my brain like a railroad builder driving spikes with a sledgehammer:

“We do not mourn the loss of those who die fulfilling their destinies.”

It seemed to Tanis that the Forestmaster’s dark eyes went to Sturm as she spoke, and there was a deep sadness in them that filled the half-elf’s heart with cold fear.

Welp, so much for subtlety. Guess that guy’s a goner. Anyhow, turns out that the heroes have to reach a lost ruined city in two days’ time or else the world is doomed, which is probably something the gods should have told them nine or ten chapters ago if it was that important. Then we get to probably the first really good scene in the book: the party coming across the dragon-slagged remnants of Goldmoon and Riverwind’s village. It’s a genuinely affecting and emotional scene that does a good job of depicting the various party members’ responses to trauma. Narratively, it’s necessary to establish what’s at stake in the coming war, making it concrete and personal instead of an abstract tragedy.

Oddly enough, he remembered the melted stones of Que-shu. He remembered them vividly. Only in his dreams did he recall the twisted and blackened bodies that lay among the smoking stones.

In general, these books do a very good job of blending darkness and light. The dark scenes like this are upsetting, but not in a gratuitous way — rather, they establish the stakes for failure and raise the tension. The light scenes give you a chance to breathe and give you reasons to care about the characters. That’s something that a lot of grimdark fantasy gets wrong: if the world is a shitheap and everyone in it is either an asshole or a victim, why should the reader care about any of it?

But then we get to easily the dumbest scene of the entire book: the party is captured by a large company of draconians, and Tasslehoff has to trick their captors into letting them go. Apparently we’re expected to believe that both the draconians and the party are so stupid that they won’t notice that a gigantic dragon right in front of them is just a big wicker puppet operated by a kender. It makes everyone look like idiots and just serves as a time-consuming roadblock between the protagonists and the ruined city. Bleah.

Then we get to Xak Tsaroth, the ruined city, where divine intervention kicks into overdrive again. Riverwind is mortally wounded in a gruesome fashion, and then a goddess saves his life in the very next scene. (Drink!) But at least we get a chance to see our first dragon, and it works fairly well. There are three in this novel, and they’re all depicted as terrifying, semi-divine engines of mass destruction rather than just a big monster for the heroes to kill. Each dragon has an individual personality: Khisanth is stupid and egotistical, Pyros is a cunning schemer, and Matafleur is mad and actually quite sympathetic. They’re not just faceless foes, either, since all of them get at least one point-of-view scene. All of this makes a big difference — if you’re going to make dragons a big part of your plot, you’d better do a good job with them.

Most of the Xak Tsaroth sequence, unfortunately, is a real slog. It’s a dungeon crawl adapted from the first Dragonlance D&D module and, as I mentioned earlier, those are next to impossible to do well in prose. Each scene description has lots of “here’s what’s to the north, east, south, and west,” describing the environment as you would for D&D players who are trying to map the dungeon. There’s a fair amount of combat, and once again it has a very round-by-round tabletop game sort of feel to it. At least the heroes aren’t your stock D&D murder-hobos. They feel despair and fear at the thought of a dangerous dungeon expedition and regret when they have to kill, rather than being excited to find treasure or keen on combat. It gives the dungeon-delving a bit more realism and emotional depth than you’d expect, which is good — it needs all the help it can get.

Sigh. No way around it… we can’t get through this without talking about gully dwarves.

In the world of Dragonlance, there’s a subspecies of dwarf called “gully dwarves” who are known for being incredibly stupid, disgustingly filthy, and uglier than sin. And we’re not just talking about a little bit stupid here, but rather severe intellectual disability. It’s not because they’re disadvantaged or misunderstood, and it’s not just a matter of education — it’s an entire race of congenitally mentally handicapped dwarves being used as comic relief. There’s a settlement of them in Xak Tsaroth, and the heroes have to manipulate them for help.

“Tell me, little one,” Raistlin said. “How many bosses?”

The gully dwarf frowned, concentrating. She raised a grubby hand. “One,” she said, holding up one finger. “And one, and one, and one.” Looking up at Raistlin triumphantly, she held up four fingers and said, “Two.”

I can see why they would want some light-hearted comedy after the recent terror and gruesome maiming, but this is just scene after scene after scene of making fun of how stupid and ugly and filthy and cowardly this entire race of people is. You could get away with this sort of punching-down comedy back in the 1980s, but it’s aged incredibly badly. Having one gully dwarf character who’s nice to the protagonists (but still stupid and ugly and filthy) doesn’t excuse any of this. It’s painful to read as an adult.

It also drags the plot to a halt. These Xak Tsaroth scenes seem to go on forever — you know there’s going to be a climactic confrontation with a dragon eventually, but first you have to watch some dwarves being dopes and watch the party wander around an empty city for a while. It’s such a relief when the mean-spirited attempts at comedy and the boxed-text descriptions of rooms come to an end and the party finally faces off against the dragon. Unfortunately, the dragon is killed by divine intervention, not by the heroes (drink!), so the heroes are mostly just there to pick up an item from the dragon’s hoard and watch the gods handle the cool part. Goldmoon is killed in the process, but is immediately revived by the gods (drink!), which seems like a real chain-yanking waste of time on the authors’ part. Just kill someone or don’t — quit trying to fake us out.

Oh, yes — and when the unaccountably load-bearing dragon is killed, it causes a tectonic catastrophe that sinks the entire ruined city under the sea, destroying the gully dwarf settlement in the process and probably drowning a great many of them. This doesn’t seem to bother the protagonists; in fact, they even prevent a bunch of gully dwarves from escaping on their way out and nobody notices or cares. Some heroes. That’s a wrap; end of Book I.

Book II, the adaptation of the Dragons of Flame module, starts with a scene of life in the heroes’ occupied homeland, which fell to the evil armies while they were off heroing. I really have to give these books credit for their depiction of war. Unlike many other fantasy novels, there’s a real focus on the low-level human cost of war: homes destroyed, lands ravaged, friends slain or captured. It eschews the usual stories about generals and the clash of armies to spend more time on the misery of ordinary people, which gives us an emotional connection to the world and makes it feel more realistic. It would feel cheap to have a story about a continent-spanning war where nobody gets hurt or inconvenienced on-screen, after all, and war without consequences is nothing more than a game.

It also shows us more of how draconians behave, and… they’re basically just shitty frat bros, I guess. Their culture seems to boil down to getting drunk and harassing women, and they don’t behave any differently from soldiers of other species. It’s a real wasted opportunity — there’s so much scope to do something cool with the concept of magically created lizard people, and instead the authors went with the most boring option. They would be a lot scarier if they were more otherworldly and not just human jerks who happen to have scales instead of skin.

Anyhow, the heroes quickly get captured and thrown into a prison wagon with Tanis’ jerkass elf cousin Gilthanas and a doddering old wizard named Fizban. The latter is clearly some sort of supernatural being in disguise — the authors aren’t even trying to hide it, and it’s kind of sad that the other characters don’t pick up on it. Raistlin is severely ill, so Fizban saves his life (drink!) and then helps the heroes escape from their cage when the slave caravan is attacked by elves (drink!). The party is taken to the elven kingdom of Qualinesti, where Tanis was raised, and he has tense confrontations with the elven side of his family. This goes badly, but Fizban convinces the elves to stop being so stiff-necked and help the heroes. (Drink!) The heroes then, after conferring amongst themselves, decide to help the elves free some slaves from one of the evil army’s fortresses.

By this point, those of you who have been following along with the drinking game… well, you’re too shitfaced to read your screen, so it doesn’t matter. Those of you who haven’t might recognize this as the first time in the entire book that the heroes have made a decision on their own without the gods nudging them around. We’re at around the three-quarters mark, and that’s a long damn time to wait for the protagonists to get any agency at all. There’s always only one reasonable way for them to go, and they’re often protected, helped, and guided by others, so it’s a tribute to the effort spent characterizing them that they don’t feel like a bunch of useless automatons. I sincerely hope the authors tone that down in the next couple of books, once they’re no longer tightly tied to the D&D modules’ plots, or else this will be a very long read.

Still, I like the elves here. They’re stuck-up assholes, but they’re not assholes for no reason — they have good reasons to resent humans, they’ve suffered greatly, and they’re in terrible danger that makes it difficult to offer aid to other nations even if they wanted to. It’s not manufactured conflict, but rooted in the setting. And they’re able to be reasonable when the situation allows, so they’re not entirely obstructionist jerks.

There’s a subplot running through Book II about “who’s the traitor?”. It seems like there must be a spy in the party! Could it be one of the heroes? Could it be Tanis’ cousin? Or could it be the random extra with no backstory whom they pick up in suspicious circumstances on their way to the evil fortress? I’ll leave it to you to puzzle out the answer. That said, even though the outcome is never really in doubt, the authors do a decent job of casting reasonable suspicion on everyone and it adds some much-needed tension during the long travelling and dungeon-crawling sequences to come.

And I do mean long, because Pax Tharkas (the evil fortress of evilness) is another time-filling dungeon delve that inserts random obstacles between the heroes and their goal. The authors do a better job of it than they did with Xak Tsaroth, mixing some plot-relevant events in with the random encounters (Laurana joining the party, Fizban’s splat, stuff about Berem, etc.), but there’s still a lot of tomb raiding and fighting giant slugs and such which feels like an extraneous excerpt from the D&D module.

Then there’s a goofy bit where the heroes stumble across a fortune in gold and turn up their noses at it:

“A treasure room!” Eben cried. “We’ve found the treasure of Kith-Kanan!”

“All in gold,” Sturm said coldly. “Worthless, these days, since steel’s the only thing of any value…”

I’d like to let this pass, but the pedant in me just can’t let it go without discussing one of the silliest parts of the Dragonlance setting. After civilization collapsed a few hundred years ago, apparently society abandoned “useless” precious metals as a currency medium and switched to making coins out of metals with practical use: steel, iron, and bronze. First of all, that’s not how coinage works. These metals aren’t fungible — they vary hugely in quality based on how they’re smelted. They’re not durable — they rust and corrode, unlike gold and silver, so you can’t store coins long-term. They’re not scarce — iron is many times more common than precious metals and it’s comparatively easy to mine more. Furthermore, steel and iron have a very high melting point, so the cost of the fuel it takes to make the coins is much greater than for soft metals. There are good reasons why steel coins, as far as I know, have never existed outside of a government-issued fiat money scenario.

Second, the way the Dragonlance authors implement it makes no sense. Rather than forging swords or armour, it works out to be more economically sensible for blacksmiths to cast coins and use them to buy swords or armour, because the metal is worth more as coins than as a useful item. When Sturm walks around Solace with a full suit of plate armour and a big sword, people should be going “Oh shit, here comes a motherfuckin’ billionaire!” because by AD&D rules, the value of what he’s wearing is a significant fraction of the value of the town and everything in it. I get that they’re trying to emphasize the post-apocalyptic nature of Krynnish society, but this is a sloppy way to do it.

Okay, I’ll stop being pedantic now, I promise. Back to the story!

In cutaway scenes, we learn that the Queen of Darkness and her dragons are searching for an immortal human named Berem who’s got a gemstone embedded in his chest, because apparently he’s the key to banishing her. Frankly, I’ve always thought the whole Green Gemstone Man plot line was the weakest part of the whole Chronicles trilogy. It’s introduced by the narrator out of nowhere near the end of this novel, doesn’t make a lot of sense, is never fully understood by the protagonists, and sidelines them in an unfortunate manner. It turns out that the key to defeating the Queen of Darkness is in the hands of some random extra we’ve never heard of before; the heroes’ story intersects his at a few points, but otherwise they’re completely unrelated. It’s so unsatisfying — it makes the heroes just the delivery system for the resolution rather than active participants who can resolve the plot themselves.

Anyhow, Berem happens to be one of the slaves held in Pax Tharkas, but he spends all of his scenes saying nothing and doing nothing. At the end he gets buried under tons of rock, then somehow shows up again during the epilogue. I get that the gem makes him immortal, but how does it get him out from under half a mountain? That’s a much taller order.

Ever since Xak Tsaroth, Goldmoon has been on a mission from the gods to find a Chosen One type who will take the scriptures she’s carrying and become the leader of the religious revival. Turns out he’s another of the slaves in Pax Tharkas — just some random extra who gets very little time or characterization. And as you might expect from the Mormon influences on this novel (more on that later), it never occurs to Goldmoon that the Chosen One she’s looking for might be a she, not a he.

If you’re getting the impression that “random extra suddenly becomes important to the plot” is a consistent theme, you’re not wrong. The authors do a great job characterizing the main cast, but not nearly as good a job on the secondary characters.

One thing I appreciate about Book II, though, is that the party picks up two people who are inexperienced at combat: Tika, a waitress from the inn in Solace, and Laurana, an elven princess. Both of them get scenes where they have to learn how to fight and kill, and it’s handled fairly realistically instead of being a matter of cheap heroics. The authors start paying a lot of attention to the psychology of battle — the fear, the doubt, the different ways people react when they’re put to the test — which makes it a damn sight stronger than the D&D-style round-by-round combat of earlier encounters.

She could not see any of the others. For all she knew, they might be dead. For all she knew, she might herself be dead within the next moment.

Laurana lifted her eyes to the sun-drenched blue sky. The world she might soon be leaving seemed newly made—every object, every stone, every leaf stood out in painful clarity. A warm fragrant southern breeze sprang up, driving back the storm clouds that hung over her homeland to the north. Laurana’s spirit, released from its prison of fear, soared higher than the clouds, and her sword flashed in the morning sun.

It’s a refreshing change from indomitable heroes who treat combat like a game to be won. (Looking at you, R.A. Salvatore…)

Fizban and Tasslehoff get separated from the party; in their side adventure Fizban magically inserts some plot-critical knowledge into Tas’ head (drink!), saves Tas’ life (drink!), and then “dies.” At the end the heroes slay the evil Lord Verminaard — did I mention that the big villain’s name is actually “Verminaard”? God, what a rubbish name. Might as well call him “Badman McWicked”. Anyhow, once divine intervention removes his magic powers (drink!), they slay him and have an epilogue where Goldmoon and Riverwind get married and everyone gets to chill out and have a well-earned break, with some foreshadowing that things are going to get rough again in the next book. The end! Phew.

Characters

This is an unusual book in that there’s no single protagonist. Instead, it’s an unusually large ensemble cast — fluctuating between eight and thirteen people! — and the point of view jumps between them often. Managing that many characters is a hell of a tall order, and it’s impressive that they mostly pull it off. When you have that many characters who need to be fleshed out in a non-doorstopper book, you have to make every sentence do double duty — everything has to further the plot, setting, or atmosphere, but also give a character a chance to shine. Let’s look at each of them and see how the authors make it work.

Specifically, let’s narrow our focus to how they employ two important tools for characterization: sympathy and contrast. Sympathy is when the author shows you things about a character that make you like them or feel sorry for them — revealing a fraught backstory, heaping them with misfortunes, or giving them a chance to do something good. It’s an effective way to build attachment to the character so that you want to keep reading to see what happens to them. Contrast, on the other hand, is putting two or more of your characters in situations where they demonstrate opposing personality traits. It gives the author twice the bang for the buck because you get to flesh out two characters at once, so it’s a particularly useful tool for large groups of protagonists.

The ranger Tanis Half-Elven gets the most point-of-view time of any of the ensemble, which I suppose makes him the closest thing we get to a protagonist. He’s the unofficial leader of the group, the one whom everyone looks to for direction in times of uncertainty, so it’s good that the authors don’t let his many personal issues keep him from being capable and assertive when necessary. No matter how messed up the situation is, he keeps on functioning because someone has to do it. Giving characters that sort of responsibility — where they’re doing it because they care about the people they’re responsible for, not because it’s a job — is a good way to build readers’ attachment to them.

But boy howdy, does he sure does have issues! The authors have leaned heavily into the depiction of half-elves as part of both worlds but accepted by neither, much like Elaine Cunningham’s Arilyn Moonblade. He grew up as a second-class citizen in elven society and hides his heritage in human society, and his fellow heroes are pretty much the only people who accept him for who he is. And as with Arilyn, the authors use his romantic relationships as a metaphor. Will he go for the elf lady who’s out of touch and doesn’t understand the reality of her situation, or the compelling but erratic and destructive human woman whom he’s fallen hard for? They’re stand-ins for their respective societies and the choice he has to make between his human and elven sides. It’s not subtle, but it gets the job done. It could have been just gratuitous angst for angst’s sake, but instead it ends up playing a significant role in the plot once they end up in the elven kingdom.

Both the “outcast” thing and the selfless responsibility are clear examples of sympathy: we keep reading because we want to see if he gets rewarded for his selflessness and overcomes his painful past. Contrast-wise, his stoic responsibility is often paired against Tasslehoff’s carefree irresponsibility. It’s no accident that the two characters Tasslehoff interacts with the most are Tanis and Flint, both of whom are different types of stern authority figures.

And speaking of stoic, we also have Sturm, a classic “knight in shining armour” archetype in a shades-of-grey world that doesn’t have any use for him. His black-and-white sense of morality could have made him an aggravating character, but the authors spend a lot of time establishing his other character traits to balance it out — he’s kind-hearted and melancholy, with the occasional flash of humour, and clings to his principles like a drowning man to a life raft. He’s often contrasted against Raistlin, with whom he frequently exchanges barbs, because seeing how they barely tolerate each other emphasizes what a principled do-gooder Sturm is and what a cynical pragmatist Raistlin is.

The character dynamic between the twins Caramon and Raistlin will drive much of the story of the next five books. They’re a great contrast against each other: Caramon is a big, strong, dumb warrior type with a big heart, while Raistlin is a frail, clever mage who’s bitter at the entire world, but they’re portrayed as sort of two halves of one whole person. Each needs the other to function, and they instinctively work well together. Caramon gets lots of characterization in later novels, but I was surprised to see how badly the authors dropped the ball with him in his first outing. He gets sympathy whenever Raistlin berates him and pushes him away, but his role in dialogue so far tends to be either “say the obvious dumb thing” or “mention how hungry he is,” so he’s a real one-note character. If I had made the drinking game about “take a shot whenever Caramon mentions food,” any participant would die of alcohol poisoning long before they finished the book.

Raistlin, on the other hand, is probably the single most iconic character to come out of the Dragonlance franchise. He’s the sort of bullied outcast underdog who’s very special but underappreciated, which is a real catnip trope for the nerds in the audience, and his well-balanced moral ambiguity gives him a sort of “bad boy” vibe that makes him mysterious without destroying his sympathy. He comes off as a sociopath in his very first scene — not from Flint’s heavy-handed “I sure don’t like that guy!” speech, but from how he clearly seems to enjoy how he makes his friends uncomfortable. But later they overplay it way too hard:

Raistlin’s voice rose with harsh arrogance. “Yes, I am smarter than you—all of you. And someday I will prove it! Someday you—with all your strength and charm and good looks—you—all of you, will call me master!” His hands clenched to fists inside his robes, his eyes flared red in the crimson moonlight.

Jesus, he sounds like a stereotypical mad scientist from a 1950s monster movie. (Still, let he who hath never dressed up as Raistlin for Halloween throw the first stone, I suppose.) With all of these negative characteristics, the authors have to work hard to build sympathy for him. His physical ailments, where he’s frail and given to fits of coughing up blood, are one approach; another is to give him the occasional pet the dog moment.

A look of infinite tenderness touched Raistlin’s face—a look no one in his world would ever see. He reached out and stroked Bupu’s coarse hair, knowing what it felt like to be weak and miserable, an object of ridicule and pity.

His role in the group dynamic is to be the cold, pragmatic voice of reason, which often contrasts him against the more soft-hearted party members. He’s the Token Evil Teammate here, though, acting rude and creepy but never doing anything outright evil. (He goes full supervillain eventually, but not for another book and a half.) During his point-of-view scenes, it’s clear that he knows and understands his allies much better than they know or understand him, which helps sell him as perceptive and clever. All told, he’s well-characterized and gives the other characters lots of good opportunities to react.

He’s a major source of ludonarrative dissonance, though. At the beginning, Raistlin tells a dramatic story about how he sacrificed his body, health, and sanity for tons of raw magical power, and then he spends the rest of the novel doing low-level 1st Edition-style “two spells per day” stuff like a total novice. The authors wanted to make him cool and powerful, but were sharply constrained by the D&D modules and the AD&D rules.

“I put them to sleep,” Raistlin hissed through teeth that clicked together with the cold. “And now I must rest.” He sank back against the side of the boat.

Tanis looked at the mage. Raistlin had, indeed, gained in power and skill.

Damn, dude, if casting a first-level spell is a big leap from five years ago, what was he doing back then? Card tricks?

And then we come to Goldmoon and Riverwind, our newcomers to the party. They’re clearly modelled on Native Americans, with a tribal culture and a feathers-and-buckskin aesthetic, and their treatment is about as mixed as you’d expect from a 1980s novel. On the one hand, they’re constantly referred to as “barbarians” by both the narrator and the characters, and what we find out about their culture makes it sound superstitious and hidebound. On the other hand, they have stone buildings, permanent settlements, and some sort of financial system, so at least they’re more than just the stereotypical tent-dwelling savages from Hollywood westerns, and the party treats them with respect and compassion.

At this point, we can’t avoid discussing how co-author Tracy Hickman’s Mormon beliefs affected the plot. The short version: Mormonism is a cult which emerged in America in the early 1800s, where a charismatic leader wrote some additions to the Christian Bible claiming that Native Americans are actually the descendants of ancient Israelites and Jesus spent some time in America hanging out with them. It is, in a very literal sense, the cult of American exceptionalism. A couple of parallels stand out clearly in Dragonlance: the platinum Disks of Mishakal, the scripture of the reborn religion in Krynn, are a stand-in for Joseph Smith’s supposed ring-bound golden plates, and having the new religion be revealed first to the Native American stand-ins before being taken over by white dudes is reminiscent of the Mormon take on American history.

It feels kind of gross because any way you look at it, Goldmoon gets the shaft here. Her role in the plot is to be the vehicle by which the gods are rediscovered, but once she’s done that and handed the responsibility of leading the new church off to a random white man, she doesn’t really have anything else to do. She hangs around for the next couple of books, but if I recall correctly it’s sort of a “and Goldmoon was there too” situation instead of her having any continuing relevance to the plot. Her arc would be so much stronger if she were actually the leader of the new movement instead of a temporary tool of the gods, but I’m hardly surprised that it ended up this way given that Mormonism’s strict gender segregation doesn’t permit women in clergy or leadership roles. And Riverwind has it even worse — his character arc happened off-screen before the novel even began, so his role in the party ends up being just “the guy who protects Goldmoon.”

That said, they get a fair amount of character development in this book. Like Tanis, Goldmoon gets sympathy from her many responsibilities and her tragic backstory. Riverwind also gets a fair amount of mileage out of his difficult backstory, and then wrings some extra sympathy out of misfortunes like being melted by a dragon or thinking he’s lost Goldmoon. They’re often contrasted against each other in scenes where he’s suspicious and she’s trusting, or he’s frank and she’s aloof. They have a rather rocky relationship for the first half of the book, in fact.

Then there’s Tasslehoff, who’s a kender, the Dragonlance setting’s version of halflings. They’re a people of stereotypes: all kender are fearless, incurably curious, driven by wanderlust, and given to stealing anything interesting that they see. The first three traits mostly work, but kender kleptomania is a problem that the authors can’t quite handle. They try to make it seem like an endearing, mischievous trait, but it just makes the kender appear to have a complete lack of empathy or concern for others because they’re incapable of realizing why people don’t want their belongings stolen. Why create a race of cute sociopaths?

That said, I expected that as an adult I’d find Tasslehoff’s antics annoying, but in fact he turned out to be a surprisingly good character. He’s not annoying in a useless way — he’s often doing useful things and being just where he needs to be. He’s not annoying in dialogue — in fact, he’s often quite articulate. He had a lot of potential to be the aggravating “makes bad decisions to add tension” character, but his friends often prevent him from doing stupid things before it can become a serious issue. He’s surprisingly empathetic and aware of social nuances, so he doesn’t cause conflict by being oblivious. He’s useful for both comic scenes and deeply emotional moments rather than being a one-trick pony like Flint, and his blithe point of view is a necessary counterpoint to the earnest seriousness of people like Tanis, Sturm, and Raistlin.

Tasslehoff, clinging uselessly to the chain, tumbled through the darkness and thought, this is how it feels to die. It was an interesting sensation and he was sorry he couldn’t experience it longer.

I wish I could say the same about Flint, the old dwarven mentor of the party, because he got on my nerves from the get-go and never stopped. He’s the same sort of comedy dwarf as Gimli from the Lord of the Rings movies — the first example of the “comedy dwarf” trope I’m aware of, in fact. He takes a bunch of funny pratfalls and often looks foolish because the rest of the party members are too cool for that sort of thing. He’s also easily manipulated by his friends, which makes him come off as not particularly bright. Honestly, I think this would be a better book if Flint weren’t in it at all. So far he doesn’t serve any purpose besides comic relief, doesn’t have much personality besides “Oh no, I slipped on a banana peel and fell down” and “I’m too old for this shit,” and soaks up time that could be spent on more interesting characters.

Tasslehoff and Flint are both comic relief characters, but there’s a crucial difference between them: Tasslehoff isn’t a schlemiel. Flint is always the butt of the joke; Tas just makes funny things happen around him. The upshot is that when the authors try to use Flint in a dramatic scene, it has less impact because the reader has less respect for him.

Two more women join the largely male-populated party in Book II: Tika the frying pan-wielding waitress and Laurana the wilful elven princess. I was afraid that this book would treat them like the sort of female characters who only exist to give male characters some development (as love interests for Caramon and Tanis, respectively) but was pleased to find my fears unrealized. Both of them get enough point-of-view scenes to sell them as distinct characters, and their shared “growing out of inexperience” theme is a good way to generate sympathy. They’re mostly contrasted against each other, with Tika feeling like she doesn’t measure up to the graceful, elegant elf, but I was pleased to see that there wasn’t any element of competition or resentment between them. Women in 1980s fantasy novels have it hard enough; we don’t need any bullshit “cat fight” dynamics to make it worse.

There’s a lot of inter-character conflict, as you’d expect with a group of this many dissimilar individuals, and it’s handled in a very mature way. They bicker, snipe at each other, and lose their tempers, but at the end of the day they still risk their lives for each other and work well together. Their conflicts are rooted in their backstories and relationships rather than manufactured on the fly by the authors, so it doesn’t feel gratuitous or annoying. All things considered, it’s one of the best executions of a large ensemble cast I’ve ever read.

That said, most of the secondary characters don’t get nearly as much time or care. Tanis’ cousin Gilthanas hangs around for much of Book II, and yet I don’t feel like he gets much in the way of either sympathy or contrast. He’s kind of a dick, and his only inter-character interaction is being shitty to Tanis, so he ends up being fairly forgettable. I seem to recall that he gets more time in the next book, but in this book I can barely think of things to say about him. Same with Eben, the newly introduced party member in Book II who ends up being a traitor — he’s just kind of bland, personality-wise, so there’s nothing to contrast against anyone else.

The senile wizard Fizban (actually the god Paladine in disguise) provides useful levity to offset the serious moments in the back half of the book, but he’s often a frustrating character. He’s an author’s pet who seems to have a copy of the script hidden in his robes, but won’t solve pressing problems or give useful information even though it would be trivial for him to do so. It’s not subtle, either — it’s clear from his first appearance that he’s some sort of super-powerful being who’s pretending to be an idiot, so he just comes off as one more annoying way in which the gods manipulate the plot. He gets plenty of characterization, but it doesn’t help much when his role often makes him feel more like an authorial contrivance than a character.

Themes

The overarching theme of the trilogy is delivered by Tasslehoff in the very last scene of this book:

But until now it had never occurred to the kender that all this might be for nothing, that it might not make any difference, that they might suffer and lose people they loved like Fizban, and the dragons would still win in the end.

“Still,” the kender said softly, “we have to keep trying and hoping. That’s what’s important—the trying and the hoping. Maybe that’s most important of all.”

Which, honestly, is a pretty great message for these difficult times. “Hope in darkness” basically sums up the whole War of the Lance, and this theme will be even more front-and-centre in the next book, Dragons of Winter Night.

The theme for this first book in particular is “restoration of faith”: humans are lost without the gods, either mired in atheism or following false idols, and the return of the True Gods heralds the return of hope for the world. Frankly, it’s a hot mess that’s not handled very well. The authors keep trying to spin it as “humanity lost their faith in the gods, and then rediscovered them in their time of need,” but that’s starkly at odds with what we’re told of the history of Krynn. The short version: Centuries ago, a particular empire of humans got uppity and thought they could order the gods around. The gods got miffed at this and destroyed the world, dropping a gigantic meteor on that empire which shifted tectonic plates and caused civilization to collapse across the entire globe — even on continents that had nothing to do with the offending empire. Millions of people worldwide died, the vast majority of whom were innocent and probably had no idea what was going on. Mountains sank, seas rose, and everything became generally awful for a long time. Meanwhile, the gods gathered their most faithful followers and fucked off, leaving the remnants of humanity to fend for themselves.

In other words, the gods come off as abusive parents. They nuke the entire world and plunge civilization into centuries of post-apocalyptic collapse, then tell humans “It’s your fault. Look what you made me do.”

“[Paladine] did not leave us,” the old man [who is a disguised god] answered, and his smile grew sad. “Men left him after the dark days of the Cataclysm. They blamed the destruction of the world on the gods, instead of on themselves, as they should have done.”

Any god who thinks that’s a rational, morally defensible statement isn’t a deity worth worshipping. Later, Goldmoon tries to explain the situation with a parable about faith in the gods being like a precious gem you lose, and it’s like, come on, sister. Ain’t no pretty gem that nuked the world and destroyed civilization — it was the gods saying “fuck this, we’re out.”

One unintentional theme that I expect they wish they hadn’t added is lots of racism. This novel predates the current conversation about race in D&D by many years, so you have races of sentient humanoids like gully dwarves and goblins that are inherently stupid or evil, respectively, and not worth treating with any respect. The book is full of gems like these:

Flint strode forward, his hands getting a firm grip on the axe handle. “There’s only one creature I hate worse than a gully dwarf,” he muttered, “and that’s a goblin!”

“I don’t consider myself a murderer.” Caramon snorted. “Goblins don’t count.”

Oof. I’ve covered the gully dwarves above; the goblins, on the other hand, serve as minor inconveniences that the heroes can kill without guilt. The speciesism demonstrated by the elves against humans, and vice versa, is much less problematic — there are historical reasons why they don’t get along, and it’s more of a disagreement between equal parties with different points of view. The draconians have no real-world equivalent, and it’s reasonable to expect that artificially created servitors of the Queen of Darkness would be inherently evil. But having an entire race of funny developmentally disabled people is something very different, and it just does not fly in the 21st century. Nearly every scene with a comically stupid gully dwarf or a malevolently stupid goblin made me wince. I’m really hoping this doesn’t come up as much in the subsequent books.

You’d expect that dragonlances would be some sort of thematic element, given that the entire setting is named after them, but they’re only hinted at a couple of times to foreshadow their appearance in the next book.

Writing

The craftsmanship in this novel vacillates between excellent and frustrating. I’ll be getting irritated at small things, like the frequent exclamation marks in narration that make it feel like a children’s book:

Both Tika and Otik started in alarm and turned to the door. They had not heard footsteps on the stairs, and that was uncanny!

And then it’ll charm me with some sort of clever small detail that conveys a great atmosphere:

The hobgoblin leaned over his saddle. Tanis watched with a kind of horrible fascination as the creature’s huge belly completely engulfed the pommel.

The narrator is omniscient and frequently switches between characters. Fair enough; that approach is probably the only way to give everyone a chance to shine with a party this large. I’m not asking for them to stick to one viewpoint for the entire book, or even one viewpoint per chapter, but I really wish they’d stick with a “one viewpoint per scene” rule. It’s disorienting because there’s often not a clear transition between one character’s viewpoint and another’s, so I kept thinking “Wait, how does X know this? Oh, wait, this is inside Y’s head now.” That’s the price you pay for using omniscient narration — you have to be really explicit about the boundaries or else the reader starts to feel as if the party is just one big hive mind.

What really bothers me, though, is that the omniscient narrator jumps around randomly in time. You’ll get a tense and dramatic scene, and then the narration will jump to a different character and tell you what they were doing during or before the action you just saw. It’s disorienting and irritating, but unsurprising, since it’s a natural consequence of the story being adapted from a Dungeons & Dragons campaign. When resolving a combat in D&D, it’s treated as a sequence of “rounds” (a unit of time somewhere between a minute and six seconds, depending on edition) where every character gets a chance to act. First one character takes an action, and then we go to the next player in the initiative order and they say what their character is doing in that same time period, and so on until everyone has described what they’re doing during that round. It works fine in a game context, but it’s a terrible way to do prose.

The editing isn’t great, which is hardly surprising for a book that was cranked out this quickly. The prose is marred by occasional comma splices, it mixes up words like “insure” versus “ensure,” and sometimes the diction is jarring. It could definitely have used another editing pass, but at least they’re all minor flaws which aren’t collectively severe enough to ruin the experience.

One unusual aspect of the Dragonlance novels is their frequent use of poetry and song, most of which was contributed by ex-TSR employee Michael Williams. Sometimes they’re diagetic, like the farewell song in Qualinesti or Tasslehoff’s bawdy drinking song; other times they’re used as prologues and epilogues. I love it, for the most part. They’re competently done, unlike some other attempts at working poetry into fantasy novels, and have a very distinct and evocative flavour. The diction and style of the free verse feels too modern-sounding for the setting, I think, even when they try to excuse it as being a translation from another in-universe language. But I love seeing tidbits of art in fantasy novels — it really helps sell the world as a real place with actual culture and history rather than just an empty stage on which to act out the plot.

And then from the center of shadows

Came a depth in which darkness itself was aglimmer,

Denying all air, all light, all shadows.

And thrusting his lance into emptiness,

Huma fell to the sweetness of death, into abiding sunlight.

Conclusion

Grade: B–

I have brought up so many complaints in my review, and yet I had a much better time reading this than I expected. It’s entirely down to the solid character work — whenever the plot was dragging or the writing got on my nerves, there would still be interesting character interactions or viewpoint thoughts that kept me invested in what happened to these people. (Well… most of these people.) If there’s one truth about writing that I’ve learned from reviewing an nigh-infinite number of these novels, it’s that good characters can cover up a multitude of sins.

Next up: a book with some dragons and more lances!

And our esteemed host has taken his red suit out of storage and dyed his beard white again! I should apologize for taking so long to respond to this, so hopefully I can make up for lost time…

-The sheer size of the party might be a relic of the days of early AD&D where parties could be very large, their numbers rounded out by henchmen and hirelings when you didn’t have as many players. Other modules with pregen characters, like the Slave Lords and the Queen of the Spiders, had eight or nine characters. These modules, incidentally, also gave me my taste for large parties both in my own fiction and the D&D streams I watch.

-I can’t remember where I read it, but the first part of the novel was a transcript of events that actually happened in play, right up until Riverwind failed a dexterity check while climbing down the vines in Xak Tsaroth and falling to his death. That was when Weis and Hickman decided “nuts to this, we’ll write things our own way.” Apparently everything that happened with Riverwind, Sturm and the dragon skull was what played out at the table.

-We’ve discussed the whole issue of game stats vs. novel presentations before. What annoyed me here was how inconsistent Weis and Hickman seemed to be in interpreting it. They correctly play up Caramon’s original 18/63 Strength score and arguably do it with Flint’s Intelligence of 7, but seeing his 18 Constitution and then reading about his constant aches and pains, not to mention what happens to him in future modules, it just comes across as really jarring. Same thing with Riverwind-his Strength nearly matches Caramon’s at 18/35, but his intro depicts him as someone who seems a lot weaker.

-Some of the better Dragonlance novels actually try to tie into what happens in the main Chronicles. Paul Thompson and Tonya Carter’s Riverwind The Plainsman gives some more context for why Khisanth targeted Riverwind when she first appears, and why Riverwind’s memories are so hazy. It turns out that Khisanth caught up to Riverwind after he escaped Xak Tsaroth in human form and started drugging him to scramble his memories. He finally managed to escape Khisanth when he shook off the drug’s effects and forced her to inhale a pouchful of the stuff, but by that point it already messed up a lot of his memories. He mostly forgot what happened, but Khisanth didn’t…and she didn’t forgive, either.

-I wonder if Flint started the trend of “older dwarf protagonists” in fantasy fiction. Examples include Bruenor Battlehammer, who’s already middle-aged when he first appears, and Ghim from Record Of Lodoss War, who’s a crotchety graybeard whose eventual fate is quite similar to Flint’s.

-When I first read these novels as a young pup, I thought Raistlin was an annoying, whiny prick. I came to understand him better later when I read the Twins series as well as the Lost Chronicles, which did a lot to humanize him beyond just the snarky, cynical know-it-all who I saw as easy to naturally dislike.

The Lost Chronicles are novels Weis and Hickman wrote in the early 2000s to fill in gaps the original trilogy left, like what happened in modules D3 and D4, or Laurana’s party and their quest for the dragon orb. Judging by Reddit, a lot of hardcore DL fans actually didn’t seem to like them much, but I thought they gave new characterization for everybody from Raistlin to Riverwind. It also showed Weis and Hickman’s growth as writers, much as we’ve seen from R.A. Salvatore and Pauli Kidd.

-There’s a guy I’ve seen on various Dragonlance forums and sites who goes by the screen name “bguy” who’s just about the biggest Laurana fan you’ll find. If he shows up, I’ll let him touch more on his views about Laurana being the true “Leader of the People”. Suffice to say that W&H really fumble the re-establishment of the gods of good through Elistan, partly because Weis detested and wanted to kill him. Hickman repeatedly had to nix it, reminding her that they couldn’t kill one of the good gods’ first new priests in centuries without it derailing the whole story.

-I have nothing to add to our esteemed host’s views on steel vs. gold, so let’s just say he hit a home run on that and move on.

-Reading through the modules, there were a lot of potentially interesting plot points that I incorporated into my own “re-imagining” of the Chronicles trilogy. One example was when the party actually makes it to Haven, home of the Highseekers searching for the “true gods”. Elistan makes an early cameo here, and it can be used to highlight his actually being sincere about wanting to find the true gods instead of just being power-hungry oafs like Hederick.

-Speaking of which, why did anybody continue listening to that fat moron when he kept getting proven wrong over and over and over and over again? Somebody like Hederick in a D&D campaign would probably push a lot of players to just ditch the refugees and leave them to their fate.

-I’ve written before about how hard dungeon crawls are to pull off in literature, but I think W&H do it as well as anyone could. They pepper the Xak Tsaroth sequence with lots of little character moments from Caramon and Sturm wanting to fight Khisanth to Raistlin’s eagerness for Fistandantilus’s spellbooks to Flint’s bigotry against the gully dwarves. It’s about a zillion times better than the execrable Greyhawk novels written by Ru Emerson-Against The Giants was a series of tedious fight scenes barely strung together by travel moments, while Keep On The Borderlands at least provided more actual character growth and had a much more bittersweet ending.

-My best attempt to play devil’s advocate for the gods of Good (ironic, I know) is that the gods repeatedly tried to warn the Kingpriest about what he was doing, but he and his minions blew them off and kept becoming more oppressive and corrupt. Some sourcebooks emphasize the need to respect mortals’ individual choices, which is why Paladine didn’t intervene directly until the Kingpriest tried to summon him. More than that, a very large chunk of society well beyond the church was implied to have become almost as rotten, such that they weren’t opposed to the idea of completely ethnically cleansing certain races, whether by death or deportation.

Of course, none of that justifies Fizban’s constant meddling now. Nor is it even necessary, given that the protagonists have shown ample desire to want to learn more about the gods and have a perfect excuse to investigate more once Goldmoon and Riverwind arrive with the staff! The draconians would be enough of a signal that there’s something much, much bigger going on than they realized, and they might need to act almost immediately!

The dragonlances are barely mentioned at all here, are they? I still can’t understand why Fizban removes Tas’s memories of them when he sees the murals in Pax Tharkas and learns about their potential value. You’d think that’s something he’d want the likes of Tanis, Sturm and Goldmoon to know about!

We’ve discussed the whole issue of game stats vs. novel presentations before.

Yep. My position on it is the same now as it was then: I am happy for them to add, change, or discard anything they want from the D&D modules as long as it’s in the service of making a better standalone story. In the apt words of Denis Villeneuve, “An adaptation is an act of violence.”

Some of the better Dragonlance novels actually try to tie into what happens in the main Chronicles…

Some of them worked out okay, and some of them just fucked up the chronology and made no sense for the characters. Turns out Sturm has met a dragon before, but he never thought to mention it during the Chronicles trilogy? Turns out Kitiara and Laurana had already met before the High Clerist’s Tower, but neither of them bring it up? That kind of thing.

But even when it works, it’s still a trap: the Dragonlance setting is too closely tied to the original heroes and their war, so once you’ve run out of unmapped bits of their history, you’re out of content. It’s the same reason why every attempt to add non-prequel content to the Lord of the Rings universe has felt wrong: the gravity of the main story is too strong. That’s why I think the Realms work much better as a setting for D&D and a long-running novel series — the epic character-based approach gives you one great story, but doesn’t give the world enough attention or leave enough room for other stories.

When I first read these novels as a young pup, I thought Raistlin was an annoying, whiny prick.

He’s definitely more of a prick in the Chronicles trilogy when you don’t know much about his motivations or see much of his human side. But even here, I think they did a decent job of making him be a jerk for clear reasons instead of just a random jerk.

Suffice to say that W&H really fumble the re-establishment of the gods of good through Elistan, partly because Weis detested and wanted to kill him. Hickman repeatedly had to nix it, reminding her that they couldn’t kill one of the good gods’ first new priests in centuries without it derailing the whole story.

Well, she’s right about that, at least. He’s more of a symbol than an actual character, and things would have worked so much better if his role had been given to Goldmoon instead.

One example was when the party actually makes it to Haven, home of the Highseekers searching for the “true gods”. Elistan makes an early cameo here, and it can be used to highlight his actually being sincere about wanting to find the true gods instead of just being power-hungry oafs like Hederick.

The weird thing about the Seekers in the novels (I don’t think it’s ever spelled out in the modules, either) is that the authors never tell you anything about their tenets. They’re a huge church who clearly have lots of temporal power, and yet their beliefs are never even mentioned.

Speaking of which, why did anybody continue listening to that fat moron when he kept getting proven wrong over and over and over and over again?

Never underestimate the power of a moron who tells people exactly what they want to hear.

I’ve written before about how hard dungeon crawls are to pull off in literature, but I think W&H do it as well as anyone could.

I don’t disagree. It’s a damn sight better than something like Escape from Undermountain, but it’s still clunky. Pax Tharkas worked much better than Xak Tsaroth, largely because the bits in between the dungeon exploring were actually relevant to the plot instead of cringey gully dwarf comedy, but even with Pax Tharkas I felt like I didn’t have a good sense of the geography or cared much about random encounters like the giant slug.

My best attempt to play devil’s advocate for the gods of Good (ironic, I know) is that the gods repeatedly tried to warn the Kingpriest about what he was doing, but he and his minions blew them off and kept becoming more oppressive and corrupt. Some sourcebooks emphasize the need to respect mortals’ individual choices, which is why Paladine didn’t intervene directly until the Kingpriest tried to summon him.

Sure, but the upper management of this one country being dicks still doesn’t justify killing all of them, plus everyone in the city, plus most of the people on the continent (most of whom are probably farmers who don’t know shit about what the Kingpriest is doing), plus people on other continents who’d never heard of Istar. It’s a real “The many shall suffer for the sins of the one” situation, and I don’t think the devil’s advocate exists who could make sense of that.

Sure, but the upper management of this one country being dicks still doesn’t justify killing all of them, plus everyone in the city, plus most of the people on the continent (most of whom are probably farmers who don’t know shit about what the Kingpriest is doing), plus people on other continents who’d never heard of Istar. It’s a real “The many shall suffer for the sins of the one” situation, and I don’t think the devil’s advocate exists who could make sense of that.

I’m not an expert on the other continents of Krynn, but from what I vaguely recall they had their own problems with genocidal megalomaniacs. And as I said, several sourcebooks imply that almost the entirety of Ansalonian society was just as bad as the Kingpriest, ranging from the people of pre-swamp Xak Tsaroth becoming arrogant and gluttonous to the dwarves of Thorbardin become selfish and demanding that Reorx cater to their every whim to Lord Soth, who we’ll meet later but suffice to say was at the highest ranks of the Knighthood despite what he…well, I don’t want to spoil it.

The best I can maybe say is that the Cataclysm was the nuclear option when everything else the gods tried failed…and as awful as the loss of life was, not intervening probably would’ve been worse, especially with a Roger E. Moore story that shows what would’ve happened if the Kingpriest actually succeeded. It was titled “There Is Another Shore, You Know, Upon The Other Side”. I haven’t read it, but from the descriptions I’ve seen it makes his Realms short story Vision seem like an episode of Arthur.

Not necessarily convincing, I know…

The weird thing about the Seekers in the novels (I don’t think it’s ever spelled out in the modules, either) is that the authors never tell you anything about their tenets. They’re a huge church who clearly have lots of temporal power, and yet their beliefs are never even mentioned.

The module DL5 “Dragons Of Mystery”, which is not technically an adventure, contains information about a lot of the playable characters and the world seen so far. The Seekers got their name from their claim that since the old gods were gone, there must clearly be “new” gods out there waiting to be discovered. Of course, most Seekers eventually just started using this as an excuse to gain temporal power. Elistan was one of the few people who was actually sincere in reconnecting with the gods. Tanis and Flint also discuss how Raistlin would expose charlatans who claimed to be clerics before the companions separated, so that might’ve been a hint that the Seekers were similar to the fakers Raistlin loved to mess with.

Well, she’s right about that, at least. He’s more of a symbol than an actual character, and things would have worked so much better if his role had been given to Goldmoon instead.

After reading the Chronicles modules and some of their updated rereleases, I imagined my own alternate War of the Lance that incorporated a lot of the ideas I got from the modules. One scene would’ve featured Elistan hatching a plan to get the forces of good to start cooperating again, but he’s hesitant because he’s afraid people would start looking to him as the great savior of everything and he could potentially end up along the same road as the Kingpriest. Fizban would snap him out of it by giving him a pep talk while trying to brighten up the sky…and instead starting a rainstorm over his head that causes a waterfall down his hat brim.

Of course, a lot of the stuff I can imagine comes from not having deadlines, word limits or editors to worry about. W&H weren’t that lucky.

Yep. My position on it is the same now as it was then: I am happy for them to add, change, or discard anything they want from the D&D modules as long as it’s in the service of making a better standalone story. In the apt words of Denis Villeneuve, “An adaptation is an act of violence.”

Margaret Weis came to agree with you, and I can certainly see the value of ignoring things like level limits and class restrictions (e.g. with Pikel Bouldershoulder the druid, Tika the dual-class fighter and thief and Dragonbait the paladin) but it just seems jarring to read the protagonists’ official game stats and how they don’t always match with what we actually read in the book. That’s why, as my own position was, I like having things like statistics and “power levels” that can guide me somewhat as a writer.

One comic I have features Thor holding up a damaged skyscraper while Spider-Man carries and sets several concrete pillars to keep the building from collapsing. Marvel’s sourcebooks often showed Thor being able to lift 100 tons, but even he was visibly exhausted from holding the building up. Spidey’s 10-ton strength rating made it easy for me to buy him carrying the pillars, but if he was the one holding up the building my suspension of disbelief would’ve evaporated.

Heroes going way beyond their limits can make for awesome moments, but I like to have an idea of what those limits actually are so I can recognize the exceptional moments for what they are.

Since I have been summoned, I will answer the call…

On Laurana being the “Leader of the People”, here’s lets look at what Goldmoon says this “Leader of the People” is meant to do:

“I do not have the power to unite the peoples of our world to fight this evil and restore the balance. My duty is to find the person who has the strength and wisdom for this task. I am to give the Disks of Mishakal to that person.”

-Dragons of Autumn Twilight, Book I, Chapter 22

So right away we see that the Leader of the People is meant to be a political leader (uniting the people) and a military leader (fighting the forces of evil) rather than a spiritual leader.

So who is it in the story that fulfills those roles of uniting the people and leading the fight against the forces of evil? That is obviously Laurana. Over the course of the Chronicles we see her both uniting the people (bringing the Dragonlances to the Council of Whitestone, providing the testimony that pretty much killed Derek’s attempt to take over the Knighthood, convincing the city of Palanthas to enter the war, convincing the people of Palanthas to accept the good dragons), and leading the fight against evil (both at the High Clerist’s Tower where she devised and executed the plan that defeated the Dragonarmies and then of course as the Golden General.) And certainly she is far more of a leader than Elistan (who pretty much gives up any leadership role early in Dragons of Winter Night and is content to serve as an advisor thereafter.) You also see Laurana have much more of an impact on the people of Ansalon than the entire religion of the gods of good does in the Chronicles. (Thousands of people flock to her banner to fight for her, and we see how beloved she is both during her entry to the city of Kalaman and given the reaction of the people to her capture, whereas the religion of good never gets more than a handful of converts in the entire Chronicles.)

It’s also notable that Goldmoon gets the quest to find the Leader of the People just a few days before she meets Laurana for the first time.

And as for Goldmoon insisting that the Leader of the People would not be found among the elves, it’s worth remembering that Goldmoon is not omniscient. As a character she can certainly make mistakes and have blindspots. (And remember she comes from a highly chauvinistic culture that hates the elves, so it is not surprising that she might have internalized her society’s prejudices to where she would never think that a young elven woman could be the leader she is seeking.) Indeed Goldmoon’s own words about why she thinks the leader of the people cannot be an elf, show this prejudice. She says the elves “want to flee the world, not fight for it”, but that is patently not true about Laurana, who did fight for the world (and indeed I would say fought harder than anyone for it, given that it was Laurana who struck all the heaviest blows against the Dragonarmies.)

And on a purely meta level, there was a post on Tracy Hickman’s website regarding the original Dragonlance proposal which described one of the planned NPC’s from that proposal:

“SHAUN-ESTI, Princess of Arsalon-veh. She … nearly died in the Cataclysm. When she recovered, she remembered little of her former life and powers. Yet her ability to command and her quickness of decision gives her the ability to reunite the land.”

And Mr. Hickman goes on to say about that character:

“The first appears to be an early– and somewhat absent minded — incarnation of Lauralanthalasa.”

“Reunite the land” sounds a lot like “unite the peoples of our world to fight this evil”, so if Mr. Hickman’s first draft of Laurana had her acting in a Leader of the People type role, it seems plausible he would have kept that role for the Laurana that actually made it into the books as well.

Since I have been summoned, I will answer the call…

I figured it was only a matter of time before you showed up. Whether it was during the Tor review (which I started commenting in its later part as “Jared, but not Shurin”), the review on the Giant In The Playground forum, or even your edits to the Dragonlance Characters section on TV Tropes (which I’ve done a lot of myself) you were always there in DL-related discussions.

And as for Goldmoon insisting that the Leader of the People would not be found among the elves, it’s worth remembering that Goldmoon is not omniscient. As a character she can certainly make mistakes and have blindspots.

I’ve currently started reading the Kingpriest trilogy (which is well outside our esteemed host’s timeframe for reviews) and I’ve gotten to the part in the first book where Ilista (who’s been tasked by Paladine with finding the next Kingpriest) meets the young Brother Beldyn and her testing ritual convinces her that he’s the person Paladine wanted her to find, although like Goldmoon she’s not omniscient and her choice eventually leads to catastrophe.

One question, though-what would Laurana do with the Disks of Mishakal if Goldmoon gave them to her? She’s obviously not a cleric herself, so how would they be useful?

To quote the great Dr. Jones. “I’m like a bad penny. I always turn up.” (At least in Laurana related discussions 🙂

And I actually feel a little bad about my comments on Laurana and the trap during the Tor reread as I think I was too critical of her decision there. (I’ve done a lot more reading of ancient and medieval military history since then and as least one full reread of the Chronicles, all of which left me much more sympathetic to Laurana’s decision.)

And yeah, Ilista’s mistake in the Kingpriest trilogy (great series BTW!) was definitely one of the original inspirations for the Laurana is the Leader of the People theory.

As for what Laurana would do with the Disks of Mishakal, even without being a cleric she could still learn from the Disks, drawing upon their teachings as a source of wisdom and strength and inspiration. You’ll notice that Elistan (who seems to have been the first person to recognize Laurana’s leadership potential) spends a lot of time with Laurana, teaching her from the Disks (which is a way of presenting the Disks to her), and Laurana herself quotes from the Disks at the end of the Chronicle which shows she took those lessons to heart.

And of course from Paladine’s perspective it would make sense to have Laurana learn from the Disks but not be a cleric herself as Paladine would want the leader of his armies to be versed in his teachings but not to be a spiritual leader herself as he would remember what happened the last time he placed temporal and spiritual authority in the same person and wouldn’t want to risk creating Kingpriest Mark 2.

Great to see these reviews!

One thought about the Goldmoon-Elistan religious leadership handoff: it’s not hard to see that being at least partly (or also) driven by the game modules.

If Goldmoon was expected to be the “party cleric” for the whole saga when the first modules were being published, then delegating the religious leadership duties to a “non-player character” like Elistan is something that would make a lot of sense at the gaming table.

If that ever was the case then it changed very quickly, Elistan features prominently as a playable character in many of the later modules, but this early on I don’t find it inconceivable.

I don’t know if anyone’s done a deep dive on it yet, but how the novels and modules influenced each other in production would be fascinating to read/hear about.

About W/H religious believes, I think the part that shows it is the moment when Caramon and Tyka get so hot after winning a battle (her first melee experience) that they almost go to a nearly forest to get laid. They are stopped by Raistlin jealousy. In the RPG books it was mentioned that Raistlin had a liking for Tyka back in the old days (may be she was kind to him?).

After that moment, Caramon and Tyka become more or less an item, and then Goldmoon gets him appart and talks to him “like an older sister would do”. She points that a) Tyka is very young, and going through a lot (that’s fair) and b) if they really love each other, they should keep chaste until marriage. Like Riverwind and Goldmoon are doing!

That was a “what the **” moment to me. Even as a young reader. After all, in Spain back then people was trying to free themselves from decades of military enforced Catholic puritanism. The talk was about sexual freedom, about woman rights, not about keeping chastity, precisely.

Caramon gots a good laugh thinking about his real big sister Kitiara talking about carnal abstinence with him!

Yeah, that’s an aspect of the Weis & Hickman Dragonlance books that always felt weird to me: the puritanical attitude towards sex. People in good relationships, like Tanis and Laurana or Caramon and Tika, wait for an appropriate time. People who do have sex are portrayed as letting their passions get the better of them, and end up miserable because of it in one way or another: Tanis and Kitiara, Gilthanas and Silvara, or Crysania when she tries to sleep with Raistlin. It feels like an artifact from an earlier, more judgemental time.

A sort of positive byproduct of Ed Greenwood being a horny Canadian hippy is that the Forgotten Realms is (at least supposed to be) a very sex-positive place.

Very much so. The Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting, 3rd Edition book even includes information about a couple of plants used as natural birth control methods, similar to silphium. It’s hard to imagine that sort of thing in Dragonlance.

Faerûn is, at its heart, kind of like “What if Renaissance Europe but Christianity never existed so they just continued with pantheism?” So there is, theoretically, none of the cultural shame around nudity, sex, etc. that came in with Medieval Christianity.

Whereas Ansalon, despite having no gods for for 300 years or so, and being all full of atheistic non-believers, still has a lot of traditional Christian purity culture stuff going on. And I think *part* of that is the difference in values from the creators, but another part of that is that Dragonlance always seems to me to be reaching for a kind of Le Morte d’Arthur chivalric tragedy kind of tone, and those stories just don’t make any sense if you divorce them from those Medieval Christian kind of values, I think.

They’re as Mormon as LotR is Catholic, but they aren’t as internally consistent as LotR, for reasons gone into elsewhere.

This book deserves A! I just Re-read it after 15 years (I’m 42 now) and it’s STILL as good as it ever was. The characters are awesome and the book doesn’t have a single boring section. Masterful, and the full Dragonlance Chronicles/ Legends series is better than LotR by a landslide.