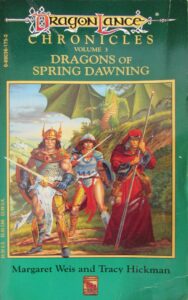

Author: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman

Published: September 1985

This, the final book of the Dragonlance Chronicles trilogy, came out a mere two months after the second book. That’s never a good sign — good writing takes time, and in all the TSR books I’ve reviewed thus far there’s been a strong inverse correlation between schedule pressure and quality. But really, how hard can it be to wrap up this trilogy? All they have to do is tie up a dozen characters’ subplots in a satisfying fashion, then find some sort of explanation for how the heroes are going to make the Queen of Darkness and her gigantic army of dragons and dragon-people disappear. No problem!

Plot

We start with a prologue about the Green Gemstone Man’s tragic backstory. Like everything related to his subplot, it makes little sense. It’s never explained how Berem’s sister dying causes the Neraka temple to arise, why the gemstone gets stuck in his chest, why his sister’s spirit is able to prevent Takhisis from manifesting, or anything like that. You could come up with some headcanon to explain it, I suppose, but they sure didn’t put any of that in the text. A prologue like this should explain things to the reader which contextualize future events; instead it just raises more questions, writing more checks that the plot won’t be able to cash. For all intents, Berem is really just an ambulatory macguffin. The only good thing I can think of to say about the prologue is that his point-of-view narration is very well done; he has a very distinct style from the usual narrator, with short, clipped sentences and a dream-like tone.

Since this came out a mere two months after Dragons of Winter Night, I strongly suspect that these books were written (or at least outlined) as one single chunk that was divided in two for publication. That would explain some of the vagaries of the last book’s plot, where one plotline is incredibly dramatic and important and the other is irrelevant. The climax for Tanis’ travelling circus subplot happens at the very beginning of this book, finally paying off all the random-seeming setup from the previous one, but I’m not sure that it should be here. If they’d put the climax of both plot threads at the end of Winter Night, it would have been a fantastic way to end that book — lots of exciting things happening, no subplots left dangling, and a great cliffhanger ending for Tanis’ crew. But two factors make that impossible. First, Weis and Hickman were working under serious space constraints, so I’m sure there was no way they could have fit both endings into the middle book; second, this book would then be much too short, because it already feels like there’s much less content in this book than in the last.

That said, I must admit that starting with a bang is a massive improvement over the weak beginning of Winter Night. There’s lots of urgency and huge stakes for both the characters’ personal relationships and their survival. Despite all the immediate danger, the authors still find time to work in vivid descriptions of the surroundings and details of the characters’ emotions. The story beats that happen are crucial to the plot and shape the characters for the rest of the book, unlike the “save the refugees” stuff which Winter Night opened with. Tanis gets a lot of character development through his lying and emotional self-destruction, Caramon gets his first real character development of the entire series, and Raistlin leaves everyone else to die. And then everyone gets sucked into an inescapable whirlpool on the open sea! Oh no! Cut to…

Raistlin, having teleported away from certain death, gets to meet the immortal historian Astinus in Palanthas. Astinus is one of the few really good side characters in this series, what with his majestic aloofness, his single-minded dedication to his seemingly pointless task, and his cold inhumanity. It would get old if he were overused, but he shows up just long enough to further the Raistlin-Fistandantilus subplot and add some of the oddness that this setting has been desperately lacking. And it really is desperately lacking, because we’ve seen just about all corners of the continent over the course of this trilogy and it’s all pretty much the same. All human settlements in this trilogy feel effectively identical, and the common people of every place from Solace to Flotsam seem to share the standard D&D culture of mashed-up medieval and early modern Western European tropes.

Then we take a short hop to Laurana, Flint, and Tasslehoff, who are also in Palanthas trying to parlay their victory at the High Clerist’s Tower into some actual military support from the people they saved. But before we get to any of that, we have to learn a ton about the Tower of Palanthas and its evil curse, first by watching Flint and Tas get fucked up by its supernatural fear aura and then by having other people spout history and exposition at Laurana.

What surprised me about this book, which I didn’t remember from reading it many decades ago, is how much work it does to set up the plot of the following Legends trilogy. Case in point: the Tower of Palanthas doesn’t make a damn bit of difference to the plot of Chronicles, but we spend a great deal of time learning about its grisly history, how scary it is, and how everyone in Palanthas feels about it because we’re going to see a lot of it in the next trilogy once it becomes Raistlin’s supervillain lair. The chapter with Raistlin visiting Astinus brings up lots of concepts that are explained in Legends — Fistandantilus, the Key of Knowledge, the nature of Raistlin’s mysterious bargain — but won’t come up again in this book. It seems clear that the authors had mapped out at least the rudiments of the sequels by this point, and deliberately left themselves plenty of hooks to connect the two trilogies. On the one hand, it’s annoying that threads are left dangling at the end of Chronicles; on the other hand, there was way too much content to fit into three mass-market paperbacks, and it’s better to have a well-integrated sequel than something awkwardly tacked onto a completed story. But having all this content that doesn’t relate to this trilogy’s plot contributes to the feeling that this book is low on content and had to be padded out.

Now back to the actually relevant parts of the story! For political reasons, Laurana gets appointed to the generalship of the Knights’ armies. [1] She’s not particularly happy about it, but she does what she must. Then a shitload of silver dragons show up to offer their aid to Team Good! Hooray! But once again the army stuff is irritatingly vague. We’re told that the dragonarmies are “scattered” and “beleaguered,” but in the last book Team Good did almost no damage to them. Their order of battle got disrupted and two dragons got killed, but there’s no reason why they shouldn’t be knocking on the doors of the High Clerist’s Tower again within a week. But even before the metallic dragons show up, the narrator is trying to convince us that the good guys have a chance of beating the dragonarmies with a handful of knights and a couple thousand untried infantry. It doesn’t make a lick of sense based on what we’ve been told so far. The dragonarmies are always as weak or as strong as the authors require for the mood of the current scene, and they become entirely irrelevant when the action moves to Neraka later on.

Ultimately, the Chronicles trilogy is just not a good war story. It’s at its strongest when it’s focusing on small groups of characters, but at its weakest when it zooms out and tries to grapple with the larger struggle of Good versus Evil. Geography, strategy, numbers, resources, time — they’re all so vague and handwavy that the reader can’t work out what’s going on outside of the immediate eyesight of the protagonists.

But wait — why did the good dragons show up now? We find out in an excerpt from Astinus’ history where he interviews Gilthanas and Silvara, who have been missing since the last book, about their secret spy mission to the city of Sanction. Apparently the reason the good dragons have been absent until now is because Takhisis was holding their eggs hostage, but when our dysfunctional duo found out that the Queen of Darkness is sacrificing the eggs to create draconians, the good dragons came roaring back for revenge. Unfortunately, this plot point requires the good dragons to hold the idiot ball. Of course the Queen of Darkness isn’t going to keep her word — she’s the literal embodiment of all evil, for heaven’s sake! What did you expect? And if we were talking about hatchlings or something I could understand how they’d be irreplaceable, but they’re just eggs. You can make more! If there’s one thing I know reptiles are great at, it’s producing tons of superfluous eggs which roll under the terrarium astroturf and go rotten and you have to scrape them out months later… ahem. Never mind.

Furthermore, this is by far the biggest turning point of the entire war, the point at which the armies of Good become able to face Takhisis’ dragonarmies on an even footing. I appreciate missing another dungeon crawl sequence, but it feels like something too important to just happen off-screen, summarized in a brief flashback. That said, I suppose I’m grateful for not having to sit through entire chapters of Gilthanas continuing to be a dick to Silvara, so thank goodness for small mercies.

We get a good character scene where Laurana and Gilthanas talk about Tanis reuniting with his old human lover, and then it’s time for a battle! The first one involving both dragons and lances! It’s… underwhelming. We see it from the point of view of Flint and Tasslehoff, whom some madman has seen fit to put on the back of a bronze dragon and send into an aerial battle. The imminent danger, the scope of the massive battle, and the majesty of the dragons are all undercut by a bunch of silliness between Tasslehoff and Flint, who is once again playing the “comedy dwarf” butt-monkey role. There’s no purpose to the comedy, though, since the last few chapters haven’t been particularly action-packed and I didn’t feel that the mood needed lightening at this point. Through a series of misadventures — and mostly thanks to the competence of their dragon mount — they manage to survive, capturing Kitiara’s second-in-command Bakaris by accident. In the process we get lots of heavy-handed foreshadowing that Flint is old and about to die, which I’ll have more to say about later.

And now we get to the clumsiest part of the novel, the point at which my enthusiasm really started to flag. Kitiara — you know, the evil Dragon Highlord whose armies Laurana just defeated — sends Laurana a message saying that Tanis is near death and offering to trade Tanis for Bakaris only if Laurana does the handoff in person with no bodyguard. This is obviously a trap. Everyone tells Laurana that this is a trap. The only way they could possibly make it a more obvious trap is if there were a giant neon sign flashing “TRAP THIS WAY ⮕” with the arrow pointing at Dargaard Keep. Only a complete dumbass, an absolute gibbering moron, would gamble the outcome of the war on a Dragon Highlord being honest and keeping her word. So of course Laurana walks right into it, and Flint and Tas follow her. Sigh.

This whole episode feels like a transparent way to move the plot along rather than an action that fits Laurana’s character. It’s enormously frustrating to watch a character who has been clever and wise up until this point suddenly decide “You know, I think this cruel, manipulative Dragon Highlord has my best interests in mind” and casually hand Team Good their biggest loss to date. At that point I blame the authors, not the character, because they apparently couldn’t think of any better way to get Laurana to Neraka for the climax. Anyhow, Laurana gets captured and disappears until the end of the book; Flint and Tas escape. Screw this whole subplot.

We then take a villain break to introduce our brand new Big Bad, a Dragon Highlord named Ariakas who’s apparently in charge of all the dragonarmies. He’s come to execute Kitiara for losing to Laurana’s army, but Kitiara manages to convince him that these losses were all part of her evil plan to lure Team Good into a false sense of self-confidence and then pounce, or something like that. She outlines her strategy to Ariakas, he says “It just might work!”, and then it’s never mentioned again. In fact, after this point we learn basically nothing about the progress of the war — it goes completely out of focus while we watch the heroes wander around the wilderness.

We also meet Kitiara’s henchman Lord Soth, Knight of the Black Rose, a former Knight of Solamnia who was cursed by the gods and became an undead monstrosity. He’s a recurring character throughout Dragonlance lore, a larger-than-life scene stealer. Mere mortals can’t stand against his fear aura and physical might, but he’s also an angsty figure who is tormented nightly by a choir of banshees chanting bad free verse at him. He’ll become important later as Kitiara’s unbeatable trump card in the dragonarmies’ factional squabbles, but for now it’s just atmosphere.

But what happened to the rest of the heroes, whom we last saw getting sucked into a vast oceanic whirlpool? Turns out that they got rescued by sea elves and taken to the underwater city of… Istar? Wait, what? Didn’t Istar get hit by a gigantic meteor that was powerful enough to destroy civilization across the globe? Oy vey. Apparently the city ended up at the bottom of the sea instead of being vaporized and diffused throughout the upper atmosphere, and now the sea elves have stashed the heroes in an air pocket inside one of the few remaining intact buildings. Tanis is simmering with uncontrollable anger — at the gods, at the world, but most of all at himself — and now instead of following his lead, his friends have to restrain him from berserking and randomly killing people whenever he gets frustrated. Caramon is an emotional wreck, separated from his twin for the first time in his life and unable to process Raistlin’s betrayal, despite Tika’s attempts at sexy therapy. Berem’s down there with them, and we find out that he’s not mute after all when Tanis tries to strangle him.

This sequence is ultimately a long bit where nothing happens. I get what the theme of it is supposed to be:

The feeling of peace and serenity present beneath the sea soothed and comforted [Tanis]. The thought of returning to the harsh, glaring world of sunlight and blaring noise seemed suddenly frightening. How easy it would be to ignore everything and stay here, beneath the sea, hidden forever in this silent world.

Should the heroes give into temptation and just chill in Rivendell instead of taking the Ring to Mordor? But it just doesn’t land for me. The heroes and Berem are all “How do we get out of here?” from their very first interactions with the inhabitants, and you never seriously believe that they would put their responsibilities aside and abandon all their friends on the surface to inevitable doom. They’ve been stashed in some mildewed, ruined shithole buildings under the sea and are eating plants off the walls, so it’s not like they’re living in the lap of luxury. All it manages to do is give the heroes some quiet character development time and introduce a couple of side characters who will never be seen or talked about again. It doesn’t do the characters’ agency any favours, either, since they get rescued and shepherded to the next plot beat by helpful NPCs instead of being able to save themselves.

After some difficulty, they talk the sea elves into sending them back to the surface. Conveniently, they end up in the city of Kalaman on the same day that Kitiara shows up to present her ransom demands for Laurana’s safe return, and then a giant flying castle full of dragons and evil stuff rocks up to keep the city in check until the deadline expires. These floating citadels were more present in the Dragonlance D&D modules, but in Chronicles they just make a couple of brief cameos in this book and are never explored or dwelt on enough for them to feel like a major part of the setting’s vibe, so it’s just sort of an out-of-nowhere “wait, what happens?” moment.

Tanis comes up with a cunning plan. He and the remaining heroes (Caramon, Tika, Tasslehoff, Flint) will sneak into Neraka, into the temple of the Queen of Darkness, the capital of her empire and the very heart of her power, and… do something, I guess? He has no idea — he’s just hoping that some sort of solution will present itself once they get there. One does, of course, but more due to contrivance on the authors’ part than because it’s a sane strategy. Meanwhile, Goldmoon and Riverwind stay behind and get written out of the story, thanks to Goldmoon’s pregnancy putting the kibosh on any further wilderness adventuring. It’s a good way to remove them from the story after they’ve served their purpose, I think. Goldmoon got a tiny role in the first half of the book as the group therapist, but Riverwind is still completely useless and has nothing to do. There’s a tearful farewell, including Tanis reconciling with Gilthanas, and then they sneak off into the wilderness.

And now we get into the endgame of the trilogy. We start this section with the god Paladine the crazy old wizard Fizban screwing up the heroes’ travel plans by chasing away their dragon mounts and forcing them to hike through the mountains to Neraka, and it’s not a good way to start the heroes’ suicide mission. Fizban’s brand of goofy comedy is staggeringly out of place at the most serious moment of the plot, and it’s frustrating to watch the chief force of good in the world play-act at being a senile old man instead of doing anything helpful. It feels like he’s being a dick, honestly — he’s being deliberately irritating and obstructive to force the heroes in the right direction instead of just telling them what they need to know.

It’s not that I want Paladine to take a more active role in events! That would just turn the story into “god versus god” with some hapless mortals trapped in the middle. Rather, I’d like either less involvement from the gods altogether or a convincing explanation for why Paladine would take such a roundabout, manipulative approach to guiding the heroes when the Queen of Darkness has no compunctions about intervening directly. The standard explanation is something handwavy about “the gods of good are big into free will and non-interventionism,” but this isn’t free will at all. Free will requires people to be able to make informed decisions, but here Paladine is keeping the heroes in the dark and forcing them to do things his way, and it’s terrible for their sense of agency.

The “travelling through the mountains” bit feels like a pointless slog. The authors throw in a brief battle scene to keep a bit of tension going. Flint dies when he overexerts himself and his heart gives out, which is an odd choice — it’s sad, sure, but it doesn’t have any impact on the plot or resonate with any ongoing themes. Tanis is still getting uncontrollably angry often, including a bit where he kills Berem in a rage. (Fortunately the Green Gemstone Man is immortal, or else the ending to this trilogy would be a real anticlimax.) Berem re-tells the origin story that we heard in the prologue, and it doesn’t improve with repetition.

All this feels like just filling time until we get to Neraka, where the forces of evil are throwing a big convention. All the Dragon Highlords are in town for a summit and they’ve brought their armies with them, so the heroes try to disguise themselves and sneak in through the crowds and confusion. This fails immediately, of course, because while our heroes have many good qualities, a mastery of guile is not among them. Tanis saves himself by throwing himself at Kitiara’s feet, while the rest end up in the temple’s dungeons with their disguises intact.

Now it’s Kitiara’s turn to hold the idiot ball. Tanis offers to become her willing servant in exchange for Laurana’s freedom. She has every reason to not trust Tanis, and yet she unquestioningly takes him along to EvilCon so he can spy on the inner workings of the dragonarmies. The authors try to make it seem like she’s secretly still madly in love with him and that’s swaying her to act against her nature, but we’re talking about a woman who just a couple months ago tried to kill her own brothers for a chance to advance her career. I don’t buy that she’d let emotion interfere with her strategic calculus on such a huge decision. Furthermore, Tanis is very hard to like here. He’s weak and vacillating, and his “plan” depends on a bunch of hideously evil assholes keeping their word. The only reason he and Laurana make it out of EvilCon alive is because super-powered Evil Raistlin shows up to be a deus ex machina, using Tanis as a cat’s-paw to assassinate Ariakas.

The Highlords’ politics all revolve around a random macguffin called the Crown of Power that we’ve never heard of before — the physical representation of the right to rule which they’re all trying to kill each other to get. It’s introduced out of nowhere during the scene where it becomes relevant, which feels sloppy, and it feels like a cheap way to simplify what could be a complex, interesting political situation into merely “get the crown.” When Ariakas dies and the Crown rolls into the crowd, a chaotic battle erupts that ultimately allows Tanis and Laurana to escape.

Meanwhile, Caramon’s group takes no noteworthy actions for the rest of the novel. Tika and Tasslehoff try to escape but fail miserably. Berem breaks everyone out of prison, then severs the Dark Queen’s connection to Krynn; Raistlin permits Berem and Caramon to reach the pillar, prevents their pursuers from killing them, then saves Tasslehoff’s life for good measure. The heroes’ role at this point is to be the living cameras through which the reader watches some NPCs resolve the trilogy’s plot. At least Tanis gets to take some concrete action to resolve the “Laurana is captured” subplot; the rest of the heroes aren’t so lucky.

Now we can’t avoid talking about the weakest part of the entire trilogy: the Green Gemstone Man and his connection to Takhisis. Apparently there’s a broken column with some jewels stuck in it, a fragment of the pre-Cataclysm Temple of the Kingpriest, which released the Queen of Darkness when disturbed. What’s special about this particular chunk of rock? Why would removing one of the gems from it allow Takhisis back into the world? Why would Takhisis implant the gem in Berem’s chest, then let him leave with it, when she needs him and the gem to open the portal to the Abyss? Why does a random gem from a random column in a long-lost temple make Berem immortal? Why does his sister’s ghost get bound to the column? How does one human ghost have the power to defy one of the chief gods of the setting for hundreds of years? Why does Berem impaling himself on the column cause the temple to collapse?

Not a single one of these questions is answered in the text. If someone tried to explain this in later sourcebooks or novels, that’s all well and good, but there’s no attempt in this trilogy to make it make sense. It’s just a macguffin in its purest form. They’re taking the Ring to Mount Doom, but here it’s a person instead of a magic ring and an old chunk of marble instead of a volcano — and for all the sense it makes, they might as well be taking a fish to a Ferris wheel.

The fundamental issue is that the authors have set up a problem — a pissed-off god with huge armies and a bunch of rampaging dragons — that’s much too large for a handful of heroes to have any real effect on. Thus, they need to come up with some sort of magic “solve the giant problem” button that the heroes can push, and that’s hard to do in a believable manner. Tolkien managed to make it work by laying everything out on the table for the reader from the very first book — the nature of the foe, the reason why the “solve everything” button will work, the difficulty of pushing it — so that it was internally consistent and didn’t come out of nowhere. Weis and Hickman, on the other hand, just say “I guess this guy has a gem in his chest or something” and expect the reader to not care about the whys and hows. It’s the backbone of the plot of Chronicles, and it feels like the authors didn’t spend even ten minutes thinking it through. It’s so deeply disappointing.

We get a fairly good epilogue, though. The temple collapses once the load-bearing macguffin is removed and the dragonarmies start fighting each other for supremacy in the resulting power vacuum, so the heroes are able to escape in the confusion. Kitiara gets away. Tanis has to convince a skeptical Laurana that he’s not working for the dragonarmies and that he deserves a second chance, instead of being given a happy ending and getting the girl for free. Caramon gets to tie off his relationship with Raistlin and begin a new life with Tika. Fizban drops plot hints about the forthcoming Legends trilogy, and then we end with Raistlin demonstrating his badassitude by claiming the cursed Tower of Palanthas as his supervillain lair. It’s nice to get some time for catharsis after the heroes have spent a whole trilogy suffering.

Characters

Tanis is shockingly unsympathetic in this book, a boiling cauldron of rage, guilt, and despair who’s constantly lashing out until his eventual catharsis at the end. He starts off feeling guilty as hell about shacking up with Kitiara, lies to his friends to cover it up, and then hits his low point when his lies are exposed. He’ll spend the rest of the book trying to redeem himself to both his friends and the reader. It’s a risky gambit to make a character this unlikable, since the reader might end up saying “Screw this guy; I don’t care what happens to him any more.” It helps that we’ve been with this character for two books already, though, so the authors probably expect to coast upon his existing audience attachment until he gets a chance to be sympathetic again. But ultimately, I don’t think it works.

Don’t get me wrong — it’s not that I want him to be perfect, or that I don’t want him to have a character arc. I think the concept of this arc is a good one, but the way it’s implemented doesn’t work for me for two reasons. First of all, his competence, leadership ability, and willingness to care for others were the primary sources of the reader’s attachment to his character, and those are all missing in this book.

Still they watched him, with no dimming of the faith and trust in their eyes. Tanis glared at them angrily. “Quit looking at me to lead you! I betrayed you! Don’t you realize that! It’s my fault. Everything’s my fault! Find someone else—”

Turning to hide tears he could not stop, Tanis stared out across the dark water, wrestling with himself to regain control.

He’s gone from being a dynamic character to being surprisingly useless, and self-absorption is not a good look on him. And second, he crosses the line with his rampant anger management issues:

“Damn it! Answer me!” Tanis raved. Flinging himself at Berem, he gripped the man’s shirt and yanked him up from his chair. Then his clenching hands moved to the man’s throat.

“Tanis!” Swiftly Goldmoon rose and laid a restraining hand on Tanis’s arm. But the half-elf was beyond reason. His face was so twisted with fear and anger that she didn’t recognize him. Frantically she tore at the hands that gripped Berem. “Riverwind, make him stop!”

He’s constantly lashing out at everyone around him in fits of berserk rage, culminating in him stabbing Berem to death over a misunderstanding on the way to Neraka, and that pushed him over the edge into complete unlikability for me. I’m willing to allow characters to make a lot of mistakes, but an entire book of someone being a dick to all of the people who care about him is too much. Stress can drive people to do bad things, sure, but if they keep behaving like an asshole over an extended period of time, it’s probably because that’s who they really are underneath — and “I got so stressed out that I straight-up murdered some dude” is not something you can just brush off with “Aww, poor guy, what a tough time he’s having.” After that point I no longer cared that much what happened to him, and felt vaguely disappointed when Laurana took him back.

Anger management issues are a particularly troubling way for the authors to express his inner torment. If this is how he reacts to stress, are we supposed to expect that he’ll be a good husband and father after this? He seems more likely to end up as an abusive or self-destructive post-traumatic basket case, and Laurana could do a lot better.

And speaking of self-destructive post-traumatic basket cases, Caramon finally gets his first good character development in the entire trilogy. We get plenty of scenes from his point of view where we see that he’s more than just “the big dumb one” or a mere appendage to his brother. His unshakable loyalty to his brother isn’t merely the trust of a dumb animal towards its master, but a deliberate moral choice by someone with a gentle nature. After Raistlin betrays him, he has to figure out how to live on his own now that his brother no longer needs or wants a caretaker. It’s good that the authors do a solid job of building him out here, because his personal journey and relationship with his twin will be the focal point of the next three novels.

Even though he spends the whole middle of the book off-screen, Raistlin is still an excellent character. He gets the conclusion of his character arc in this book, where he turns out to be the chessmaster who brings down the Queen of Darkness so he can thin out the competition in would-be evil overlords. It fits well with what we’ve seen of his character already, advances the book’s theme, and allows him to help the heroes without redeeming himself in a stereotypical way. He’s still willing to commit evil acts for the sake of power, but he’s not so far gone that he can’t feel sentiment or regret. We still get only bits and pieces about his relationship with the long-dead archmage Fistandantilus, though, which is a crucial plot point but remains a mystery that the authors leave dangling until the sequel trilogy.

Tasslehoff is still the emotional heart of the story, and it’s his reactions to events like Flint’s death or the dungeons of Neraka that really sell the big story beats. He’s the most cheerful, optimistic, fearless member of the party, so when things make him sad or afraid, it’s serious business indeed. That said, he was a stronger character in the previous book when he got a chance to do things that were important to the plot. Here he does some comedy scenes with Flint and acts as a camera for some of the dramatic scenes, but he doesn’t actually do much. None of the heroes have much agency in this book, actually, but it’s the most noticeable with Tas.

And Flint… I keep asking myself, what was the point of Flint dying? He doesn’t die doing anything dramatic or relevant to the plot; he’s just an old man with heart disease whose heart gives out when he climbs a mountain too hard. It’s foreshadowed quite a ways in advance, but unlike Sturm’s death, it doesn’t really add anything to the story, do something important for his character arc, or support a theme. It’s more like he’s just stuffed in the fridge so that the other characters get a chance to emote. I don’t mind it — he was no longer useful to the plot, and it gives his friends an opportunity for character development — but it seems like his death could have had a lot more impact if the authors had played it differently.

Laurana starts off as a well-rounded character. She’s doing heroic things, but she’s not stereotypically heroic; she’s just stubbornly doing what needs to be done even though she’s scared and heartsick. And then she walks into the world’s most obvious trap like an imbecile, even after everyone tells her it’s a trap, because the authors had to find a way to write her out of the story and give Tanis a motivation. Argh! At least she’s not a useless damsel in distress — she grabs a sword and fights her way out of Neraka when she gets a chance, and she doesn’t trust Tanis any more than he deserves until he gets a chance to dramatically prove which side he’s on. I just wish the authors could have handled her disappearance by making the bad guys do something clever rather than having her do something monumentally stupid.

Meanwhile, her brother Gilthanas is being such a total dick. He’s had months to get over the whole “my girlfriend is a dragon” thing, yet he continues to make an emotionally trying situation even harder for her with his constant microaggressions and bitterness. Just sack up and get over it already, you utter knob-end. It’s hard to have a lot of sympathy for his “this beautiful lady who’s super into me can turn into a dragon, oh no, woe is me” act.

And now onto the villains! When a character who’s important to all the other characters — sister, girlfriend, adventuring companion — turns out to be evil, my thoughts immediately jump to “Is this going to be a ‘redeemed by the power of love’ story?” It wasn’t clear whether she was redeemable from the last book, since Kitiara got so little screen time there, but she crosses the moral event horizon right away in this book by being willing to kill her lover and younger brothers for a chance to capture the Green Gemstone Man and gain the Dark Queen’s favour. This sets up two contradictory character developments for her; I like them both, but I wish the authors had been willing to choose just one.

Lord Soth is constantly commenting on how she’s so in love with Tanis, in a subconscious unwilling-to-admit-it-to-herself kind of way, that she can’t bring herself to kill him. In theory, this explains why she keeps giving him second chances and why she lets him and Laurana escape at the end. But we never really see what about Tanis is so appealing to her, or what makes him different from all of the other men available to her, so it ends up being an informed attribute — and it certainly doesn’t square with the vengeful, single-minded, self-interested person we met in Chapter 3. Is she hopelessly in love with him, or is she an amoral, unsentimental murderer who “could kiss you and kill you without drawing a deep breath in between”? The authors want to have it both ways, but it just leaves me confused.

The new Big Bad of the evil forces, Emperor Ariakas, is basically just another Verminaard. The other characters talk him up a bunch:

Gilthanas’s fist clenches, his face is pale with anger and fear.

“Lord Verminaard was nothing, nothing compared to Lord Ariakas. This man’s evil power is immense! And he is as intelligent as he is cruel…”

Yadda yadda, so on and so forth. But it’s all just shilling, all tell but no show, and what we actually see of him is just standard Evil Overlord material. The authors try to establish his scariness by employing the most irritating of villain tropes: a willingness to casually kill anyone who displeases him in any way. That doesn’t sound like an intelligent villain to me; rather, it makes him look like a short-sighted asshat with no impulse control. He displays no human traits, does the usual evil gloating, and then gets killed at the end. It’s no great loss to the plot when that happens.

Themes

The theme for this book is clearly spelled out for you at the end, just in case you didn’t pick up on it:

Orange flames lit the sky where wheeling dragons fought and died as their Highlords sought to escape or strove for mastery. The night air blazed with the crackling of lightning bolts and burned with flame. Draconians roamed the streets, killing anything that moved, slaughtering each other in their frenzy.

“So evil turns upon itself,” Laurana whispered, laying her head on Tanis’s shoulder, watching the terrible spectacle in awe.

Evil is fundamentally self-defeating. The Queen of Darkness encourages constant conflict among her followers to weed out the weak, but it fragments her otherwise unstoppable army into a bunch of feuding fiefdoms and ends up weeding out some of the strong to boot. Takhisis’ betrayal by her servant Raistlin is the proximate cause of her downfall, and her forces collapse into civil war the minute she’s not there to restrain them. The forces of good, meanwhile, have mostly worked out their issues and united to oppose her.

Personally, I’ve always thought that “survival of the fittest” is an utterly useless axiom for anything except base, brute survival. You sure as hell can’t build a society on it, and only the most terminally dense of people would think it was a good idea to try. It selects for people who are good at violence and manipulation, not for people who are useful or necessary to society. Here the Dark Queen is happy to let Ariakas — her most powerful mage and most dreaded general — die if he can’t 100% perfectly protect himself all the time, kicking off a wholesale slaughter between her followers, when she’s at war with the entire rest of the continent and can’t afford to lose either a general or huge masses of troops. I’d give the authors a bollocking for that, except that there seem to be plenty of dopes in the real world who think that this is a workable ethos. Sigh.

Writing

It feels more rushed than the writing in Winter Night, with more comma splices and a couple of typos. But Weis and Hickman have clearly been getting a lot of practice: the prose feels somewhat less clumsy here than it did back in Dragons of Autumn Twilight, with better descriptions, fewer random adverbs, and narration that’s more often close third-person than omniscient. It’s serviceable but unremarkable, and I don’t have much to complain about.

The poetry, still contributed by former TSR employee Michael Williams, is generally weaker in this book than in the previous two. It feels very abstract, and the diction isn’t as tight. I thought the kender mourning song was quite good, but Lord Soth’s lament and Raistlin’s farewell have lots of bits like “as a child opened in parabolas of fire” or “the deep complexity lodged in the veins” which feel less like something someone from Krynn would have written and more like a modern poet trying too hard. Free verse is a dangerous trap for poets; the lack of structure provided by rhyme and metre provides a huge scope for well-meaning mistakes, and it’s a rare poet who can consistently avoid them. It’s especially awkward for the poems that are supposed to be lyrics to a song — you look at the ragged lines and think “How could anyone possibly put this to music?” (Also, why are most of the poems about sharks?)

Conclusion

Grade: C+

It’s not a terrible book. It has some good characterization, some exciting scenes, and shows us more of the setting. But ultimately it’s dragged down by a plot which makes no sense, has long stretches of flagging tension, requires the characters to act like idiots, and gets resolved by Berem and Raistlin while the heroes watch. The overall impression is… meh.

How could you fix this plot? A few ideas spring to mind, but they’d require some pretty extensive changes. Most importantly, the Green Gemstone Man has to go. Give the Queen of Darkness a reasonable weakness, explain why it makes sense early on, and let the heroes be the ones to exploit that weakness instead of some random macguffin guy. Next, fix the war. What are the dragonarmies doing? How does Team Good stack up against them? Kitiara has a cunning strategy — how did it work out? Finally, if Laurana needs to get captured, do it in a way that doesn’t require her to hold the idiot ball. Let her be ambushed, or separated from her forces, or swept away in the claws of one of Kitiara’s dragons, or something — anything as long as she’s captured while taking action towards a goal that makes sense. Any of the above would earn this novel a higher grade, but as it is it feels like a lukewarm conclusion to the trilogy.

Footnotes

[1] In the last two books, the dragonlances are described repeatedly as needing special training to use. The authors employ this on at least two occasions to keep Laurana involved in the plot:

“Therefore I appoint to fill the position of leadership of the Knights of Solamnia, Lauralanthalasa of the royal house of Qualinesti […] who is the most experienced person currently in the field and the only one with knowledge of how to use the dragonlances.”

But if there’s any training required to use them aside from “put the sharp end in the dragon,” it’s never shown or mentioned.

This latest post confirms once and for all that our esteemed host needs a new calendar, and that he moonlights as Santa Claus in his spare time. Now, on to business…

-Once again we see how challenging it can be to convert game modules into novels. Tanis’s party forming a traveling circus and getting caught in the ruins of Istar led to some really cool moments in the modules (helping the sea elves fight the Dragonarmies’ underwater forces by destroying the power source of the demonic sea monster leading them, helping Maquesta Kar-Thon become the new pirate queen and preventing Kitiara from capturing Berem) but in the novel they become mostly boring filler. It really raises some questions as to know what to keep and what to trim. It’s not something I’d envy W&H for, especially when they’re novice authors.

-Our esteemed host mentions how rushed this book feels. I wouldn’t be surprised if Tracy Hickman’s writing a couple of the later Chronicles modules (specifically DL10 and DL13) in between writing this novel is one of the reasons it was rushed, or perhaps Margaret Weis had to do more of it by herself. Raistlin’s prominence in a lot of the novel might be a sign of this (and Hickman has always stated that he never wrote Raistlin, who was pretty much a Weis-exclusive character).

-Our esteemed host’s criticism of how idiotic Laurana’s capture is is spot on. A Laurana fan by the name of ‘bguy’ (who I’m honestly shocked hasn’t shown up yet) tried to justify it as Laurana being exhausted by the stress of leading the war effort with little sleep and having consumed too much wine, which the text notes she can’t hold very well. From what I’ve heard, this passage also caused a dispute between Weis and Hickman, with Weis arguing that Laurana would never fall for such an obvious ploy while Hickman said that she would do so out of love for Tanis. Weis eventually went along with it as a means of advancing the plot.

-Related to that, I couldn’t understand what the hell Tanis ever saw in Kitiara when I first read this series 30 years ago and I still can’t understand what the hell he sees in her now. She comes across as an incredibly toxic person (and her sexuality has nothing to do with this, of course) and I’m baffled as to why Tanis keeps thinking about her when Laurana threw away almost everything she had in life to support him. Laurana repeatedly risks her life with the rest of the Heroes, she gave up her respected position in the Qualinesti court to the point where her father all but disowns her, and her efforts to protect him end up getting her captured and nearly sacrificed by Kitiara in Neraka. It should be obvious which of them is the keeper.

-Given Tanis’s increasingly short temper and lashing out during the journey to Neraka, I can actually see why he’s so upset. A combination of shame at deserting his friends for a roll in the hay with Kitiara, guilt over Laurana being captured, and the frustrations that come with having to put up with Fizban’s crap would probably all boil over at some point. Could W&H have done a better job actually communicating this?

-I’m kind of shocked at our esteemed host’s views that the good dragons could just make more eggs. The problem was that Takhisis could easily turn them all into omelettes if she wanted to, and she basically forced them to stay out of the conflict by holding a knife to their kids’ collective throats. We don’t necessarily know how fertile Krynn’s dragons are compared to real-life reptiles, so lose enough of those eggs and the entire species might be endangered.

-I concur with our esteemed host’s views of how the discovery of the good dragon eggs in Sanction is probably too important to happen off-screen, and now he knows how robbed I felt by the previous books glossing over the hunt for the Hammer of Kharas and the quest to Icewall. When we finally get the full story in the Lost Chronicles, the dungeon crawls actually don’t last very long and characters ranging from Flint (who actually comes across as more Gimli than Grampa Simpson for once) to Laurana to even Riverwind get some impressive development. They also provide more action that I feel the original Chronicles often lacked, especially in this book.

That said, how do you present something like that effectively?

-The contrast of Flint’s and Sturm’s deaths is why I’m often reluctant to kill many of my own fanfic characters off except for the likes of one-shot villains. I seem to recall Weis saying that she wanted to show that not every death is going to be a heroic sacrifice the way Sturm’s was-some people will simply die of illness or accidents. I actually wondered on a forum many decades ago why Flint had to die, and one poster suggested it helped spur Tas’s character development, which we see later on in the Legends series. But my reaction when I first read it was similar to our esteemed host’s, namely that I didn’t really see a reason for it. Did W&H just implement it poorly, the way they apparently did Tanis’s anger issues?

And just as our esteemed host keeps harping on Sturm and Kit going to the moon, I will keep harping on how much it bugs me that Flint is supposed to have an 18 Constitution, but half his scenes have him suffering everything from rheumatism to lumbago (which he gets in a prequel novel) to his heart problems.

-I wonder if Fizban could serve as a ‘How Not To’ guide for how to write a mentor figure. The Tor review series had people pointing out that if Fizban pulled some of the sketchy stuff he does in the novels as a game NPC (forcing the party to flee the Inn at the start of the series, constantly getting lost when he tries to lead them through the mountains) a lot of players’ frustrations would probably boil over like Tanis’s and abandon or kill him. It’s not necessarily even that effective-the Heroes were already inclined to go to Haven (from where they would’ve been directed to Xak Tsaroth) once they see the blue crystal staff, while leading the party in circles through the mountains accomplishes…what, again?

-A good chunk of our esteemed host’s review could be TL;DRed as “different characters pass the Idiot Ball around”. Apparently Tanis and company never thought to consult any of the Solamnic forces in Kalaman about the Dragonarmies’ security precautions and anything the Solamnic spies managed to find out, which the players can do in the modules. It was just deus ex machina that Kitiara happened to be nearby and vouches for Tanis.

-I honestly feel kind of bad for Goldmoon and Riverwind. They don’t get much focus beyond the first volume, and mostly seem like ballast. I was dismayed at their lack of focus, which I suspect led me to try and give all my own protagonists at least some screen time. In particular, I’ve been shifting the spotlight from one protagonist to another with each given ‘novel’.

-I’m a bit surprised our esteemed host didn’t have any comment on Fizban’s description at the end of the novel where he says the Kingpriest was a ‘good’ man. After thinking about it for a while, I noted how in a sense the Kingpriest’s righteousness turned into self-righteousness. History has multiple examples of people doing horrific things for what they consider to be the greater good, from historical revolutions that brutalize the very people they claim to be fighting for and destroy large amounts of cultural heritage to activists today who justify doxxing and social media pile-ons and brush off the ruinous impacts it can have on peoples’ lives, especially if they’re innocent, by saying that the suffering of a couple of innocent ‘people with privilege’ doesn’t matter.

Raistlin’s prominence in a lot of the novel might be a sign of this…

He’s actually not in much of this one, at least compared to the other two books. He has the dramatic “screw you guys, I’m out” scene on the boat, the scene with Astinus, and then he’s completely gone for most of the book until his turn as a deus ex machina at the very end.

From what I’ve heard, this passage also caused a dispute between Weis and Hickman, with Weis arguing that Laurana would never fall for such an obvious ploy while Hickman said that she would do so out of love for Tanis. Weis eventually went along with it as a means of advancing the plot.

Oof. Weis was right and Hickman was wrong, then. I’m not particularly a stan for Laurana in particular, but it bothers me that they put so much good work into developing a character over the course of two books and then tossed it in the bin at the end. It’s like watching an Olympic runner trip and break a leg on the final lap.

Related to that, I couldn’t understand what the hell Tanis ever saw in Kitiara…

Well, as Emily Dickinson put it, “The heart wants what it wants.” People get attracted to toxic people and form bad relationships all the time. I’m fine with the concept of this character arc, but I think it would have worked a lot better if the authors had made it more clear what they saw in each other. Their expression of Tanis’ attraction to Kitiara seems to mostly be him remembering how much he likes her eyes, and we never really learn anything about why she’s attracted to him, but we need to learn more about their emotional connection to make their toxic relationship understandable.

Given Tanis’s increasingly short temper and lashing out during the journey to Neraka, I can actually see why he’s so upset.

Oh, I quite agree. He has lots of reasons to be upset and I can understand him boiling over, but it’s a problem of degree. “I got so stressed that I lashed out at my friends” is something that can both boost sympathy and develop everyone’s characters the first time it’s used, but if you keep doing it for an entire book it gets old. And then “I got so stressed that I stabbed a defenseless man to death in a rage” is way, way beyond the sympathy line.

That said, how do you present something like [the mission to Sanction] effectively?

That’s a good question. There’s plenty of bits that could have been cut or trimmed down to make room for it, but I think I also wouldn’t have liked having Gilthanas and Silvara splitting off into a third point-of-view party, because that seems like too many simultaneous storylines. Frankly, I’d rather have G&S piss off and have the heroes discover the secret themselves — maybe that means them going to Sanction instead of hanging out underwater, or maybe there’s someone else they can interrogate or some clues they can find that lead them to the realization without having to go to Sanction. Whatever it takes to make the heroes more relevant.

I seem to recall Weis saying that she wanted to show that not every death is going to be a heroic sacrifice the way Sturm’s was-some people will simply die of illness or accidents.

Sure, and that’s fine. Flint’s death didn’t need to be dramatic or heroic. But my take on writing is that everything needs to serve at least two of the following to feel right: character development, plot, setting, or theme. If he’d died peacefully in a way that served an important theme of the book or trilogy, I’d be all in favour of it. But here it’s only useful for character development and nothing else, so it feels unnecessary. That said, Flint was never a character who had much relevance to… well, anything. Your description of him as “Grandpa Simpson” made me laugh out loud, because that’s basically his only role here. I wish they’d been able to cut him entirely.

I’m a bit surprised our esteemed host didn’t have any comment on Fizban’s description at the end of the novel where he says the Kingpriest was a ‘good’ man.

I’ve got some notes about how messed up the morality is in the Dragonlance universe, yeah. It’s not really a balance between good and evil; it’s a balance between three different flavours of complete dicks, none of whom represent “good” per se. Paladine saying that the Kingpriest was a “good man” is not doing good any favours, since he was a crazy person who was big into genocide and re-education camps. Evil is just straight-up evil. And neutral, well… I really wish they’d either gone with a law-neutrality-chaos axis or de-emphasized the neutrality aspect instead, because the neutral faction ends up being a bunch of weirdos with no clear ethics or obvious role to play. When your evil guys are all “We want to eat babies!” and the good guys are all “We can’t let any babies get eaten!”, there’s not a lot of room for compromise there. Nobody’s going to appreciate the guy whose point of view is “Let’s allow them to eat some babies.” If the neutrals feel that the evil faction isn’t eating enough babies, will they have some baby snacks to restore the balance? If so, then they’re no longer neutral — you can’t eat babies and claim to not be evil. Whereas in an order-versus-chaos system, you have two sides who disagree on the means to achieve their objectives rather than the objectives themselves, and compromise is a much more defensible position there.

The short version is that the morality system is vague and weird enough that it can be used to express whatever idea the author wants to get across in a given book. Trying to make some sort of objective sense of it is a fool’s errand.

Well, as Emily Dickinson put it, “The heart wants what it wants.” People get attracted to toxic people and form bad relationships all the time. I’m fine with the concept of this character arc, but I think it would have worked a lot better if the authors had made it more clear what they saw in each other. Their expression of Tanis’ attraction to Kitiara seems to mostly be him remembering how much he likes her eyes, and we never really learn anything about why she’s attracted to him, but we need to learn more about their emotional connection to make their toxic relationship understandable.

Here’s a question I’ve been chewing on for the last few weeks since our esteemed host wrote this. Namely, when does something like this serve as establishing a character as flawed, and when is it just plain bad writing on the author’s part? Our esteemed host criticized the Tarsians’ having a grudge against the Solamnic Knights for centuries, while I saw it as similar to the idiotic grudges some populations have against minorities for things that either happened centuries ago (the Jews) or are almost certainly flat-out lies (the Romani). Meanwhile, I criticized the fact that people were still listening to Hederick while our esteemed host reminded me that people have continued listening to moronic blowhards even when they’ve been repeatedly proven wrong.

So how does one decide which is which?

I think there are two criteria that determine whether the author leaving details out is okay or not: plausibility and importance.

Plausibility: If the author doesn’t explain something, will the reader automatically fill in the blanks themselves with something plausible that doesn’t break their immersion, or do they have to stop, think about it, then write some sort of fanfiction headcanon to make it make sense? In my case, Hederick seemed like a pretty standard instance of the “sociopathically ambitious politician” archetype that I’m familiar with from the real world, so it didn’t occur to me to dig deeply for details. The Knights, on the other hand, are something that I don’t see happening in the real world: the entire population turning on a group of rich, powerful, previously well-liked people on a dime for something they couldn’t have done anything about. (The only similar cases I can think of in the real world, like the French and Russian Revolutions, were situations where the rich, powerful minority had been brutally abusing the populace for centuries.) Mobs punch down when they’re looking for scapegoats, not up.

With the Tanis/Kitiara relationship, I felt like I couldn’t fill in the details. Every relationship is unique, so there’s much less room for authors to just say “By the way, they’re in love” without at least hinting at how and why. All we have to go on is “he likes her eyes” and “they like to bang,” and that’s just not enough material for me to construct a headcanon from.

Importance: How badly does the reader need to know this detail? The political shenanigans with the Seekers in Solace weren’t particularly important to the story except as a means to get the party on the road at the very beginning, so I didn’t really care that much about Hederick and how he established his power base. On the other hand, the relationship between Tanis and Kitiara is very important for both their characterization and the plot, so the reader really needs to understand how these people are connected. Likewise, the Tarsians’ dislike of the Knights is a major plot point that leads to the party’s arrest and trial, so it needs to make sense.

Interesting review though since I am a Laurana stan I will speak up for her in regards to the trap plotline as I think you were rather unfair to her on that point.

To begin with generals meeting in person with the enemy with few or no bodyguards present, is nowhere near as ridiculous as you make it sound. Meetings of that type were common practice in ancient and medieval warfare. As just one example Hannibal Barca and Scipio Africanus met in person before the Battle of Zama with each of them having only a single translator present, and no one would call them imbeciles. They were two of the greatest generals in all of human history. For another example during the Sicilian War, Octavian and Marcus Antonius went onboard the flagship of the enemy commander Sextus Pompeius to negotiate a peace accord (where they were in so exposed that even Pompeius’ own admiral, Menas, pointed out to him how easy it would be to just sail away and take both of their enemies prisoner) and again Octavian was hardly a dumbass. He might well be the greatest political genius in all of history. So Laurana is actually in very good company in being a general that was willing to meet in person with the enemy.

Laurana also had good, logical reasons for thinking she could trust Kitiara there. Remember Kitiara already had the perfect opportunity to kill or capture Laurana in the previous book when she confronted Laurana on the tower wall at the High Clerist’s Tower at a time when Laurana was alone, unarmed, and so exhausted from having just used the Dragon Orb that she could barely stand. (You’ll remember that at point in that prior encounter Kitiara even had Laurana’s own Dragonlance aimed right at her heart.) Laurana knows that Kitiara could have easily killed or captured her during their last encounter, so the fact that Kitiara did not try to physically harm her there gives Laurana very good reason to believe that Kitiara must genuinely not want to harm her (probably out of respect for Tanis’s feelings) and thus to believe Kitiara’s message. (And especially since in that same encounter Kitiara had also acted in an honorable and sentimental manner towards Sturm which further supported the idea that while she was an enemy, she was an honorable enemy.)

As for the others telling Laurana it was a trap, yes but lets look at that from Laurana’s perspective. While Flint and Tas told her they did not believe the message, they didn’t really give her any specific evidence that Kitiara was a dishonorable person. (They both know Kitiara personally, and yet they did not give Laurana a single example of Kitiara herself doing anything treacherous. Instead their argument just amounted to “she’s a Dragon Highlord” which really isn’t that convincing an argument since even an evil cause can have honorable people fighting for it, and Laurana’s own prior experience with Kitiara was of her being an evil but honorable opponent.)

Furthermore, just consider Laurana’s experiences throughout the Chronicles up to this point. She has repeatedly had the male party members step in to try and keep her from danger. Tanis and Gilthanas didn’t even want to let her join the party, Lord Gunthar and Sturm both tried to send her away from the High Clerist’s Tower during the siege, and Tas repeatedly tried to talk her out of using the Dragon Orb. And up to this point in the story, Laurana has not only survived, but succeeded brilliantly every time she went against the overprotectiveness of her male friends. (The whole war would have been lost in the last book if she hadn’t insisted on staying at the High Clerist’s Tower and using the Dragon Orb.) Thus, I think it’s understandable that when she (yet again) experiences her male friends trying to keep her out of potential danger that she would dismiss that as just another instance of her male friends being over-protective (and rather patronizing) and decide to trust in her own instincts instead, since so far she has been 100% right every time she did that.

I would also disagree that Laurana falling for the trap devalues all her character work. Wanting to be with the person you love when they are dying doesn’t make you weak, and deciding to trust an enemy that you have valid, logical reasons for believing you can trust, doesn’t make you foolish. But even if you take the harshest interpretation of her falling for the trap, it is still just one mistake (born out of her being a brave and compassionate person.) That hardly diminishes all her great character growth and heroic actions that occur both before and after the trap incident. (Indeed I would say that the Laurana scenes in Neraka where she stands strong and brave despite being surrounded by thousands of enemies and seemingly betrayed by Tanis are some of the most heroic moments in the entire series, and show why Laurana is the best character in the series.)

I think the comparison to Roman generals is not very applicable. Roman culture was extremely honour-based, so to give your word of safe-conduct to someone important and then dramatically break it in public would offend the dignitas of the oath-breaker’s entire family and most likely prove fatal to their political and military career. The Dragon Highlords worship the goddess of being incredibly super evil — who is herself a treacherous oath-breaker — and lead a deracinated army of vat-grown creatures with no culture, so I wouldn’t trust them as far as I could throw them. Furthermore, there’s a vast difference between a public diplomatic meeting of the heads of two opposing armies and the shady “tell no one about this and don’t bring anyone” setup for the trap.

It’s true that Kitiara had the chance to kill Laurana earlier but didn’t. That doesn’t indicate much, though, because Laurana wasn’t the Golden General at that point — she was just another one of the exhausted, sad defenders of the High Clerist’s Tower, and killing her wouldn’t have accomplished much. Once she becomes the general of all of Team Good’s armies, the situation is very different.

Thanks for the thoughtful response! Ultimately, though, everything about reviewing literature is subjective. Me saying “this thing didn’t work” isn’t an objective truth, but my impression of a complicated matter — and for me, the whole “Laurana walks into a trap” storyline just didn’t work given all the setup that led to that point. That said, in a situation like this I blame the authors, not the characters. And I agree with you that although she doesn’t get a lot of screen time in Neraka, her appearance there is memorable and well-done.

The Roman examples were just one example. I use it because of the historical reputations of Hannibal Barca and Octavian since their examples show that even the absolute greatest of military and political leaders were willing to act as Laurana did, but there are plenty of examples from other cultures of very capable leaders meeting in person with the enemy while having few or no bodyguards with them. (For just a few other examples: King Harold Godwinson rode up by himself to the enemy army to parley (or more accurately to insult) the enemy commanders prior to the Battle of Stamford Bridge, Saladin met in person with envoys from the Assassins while only having two of his bodyguards present, and Benjamin Franklin and John Adams went onboard the flagship of Admiral Richard Howe to negotiate with him during the American Revolution.) And for a more recent example from just a couple of years ago, shortly after the Taliban took Kabul, the Director of the CIA went there and met in person with the leader of the Taliban. The fact that these kind of meetings have occurred in such a wide number of cultures (and are still happening even today) shows that Laurana wasn’t doing anything inherently unreasonable by agreeing to meet with Kitiara.

And yes Kitiara is a Dragon Highlord, but that doesn’t automatically mean she worships Takhisis or is devoid of honor. (Just as how in World War 2, not every German general was necessarily a devoted Nazi.) And certainly Kitiara’s actions at the High Clerist’s Tower, where she acted in an honorable fashion and did not try to harm a defenseless opponent, were very different from what you would expect from a devoted follower of Takhisis. Those actions suggested that Dragon Highlord or not, Kitiara still had a core of decency to her. So while Laurana was clearly wrong in her assessment of Kitiara, I don’t think she should be faulted for assessing Kitiara as an individual rather than just blindly assuming that since Kitiara was a Dragon Highlord she had to be a monster.

And I think you are overstating the shadiness of Kitiara’s message. No where in the message did Kitiara tell Laurana that she couldn’t tell anyone about the message. (Gakhan did tell Tas to deliver the message to Laurana when she was alone, but Tas never mentioned that to Laurana, so all Laurana had to go on was the message itself, which contained no limitations on who she could tell.) Nor did the message tell Laurana that she couldn’t bring anyone with her. It did limit her to two specific bodyguards, but it’s not inherently unreasonable to want to limit how many bodyguards someone brings to a prisoner exchange (see the story in Le Morte de Arthur of Arthur meeting with Mordred on the fields of Camlaan for a literary example of what can go wrong if there are too many armed warriors at a tense meeting), and Flint and Tas are both capable fighters, so it’s not as though Kitiara was insisting Laurana come without protection. The message also didn’t prevent Laurana herself from bringing weapons with her and the exchange location was to be right outside the walls of a city controlled by Laurana’s army. (Thus in the message itself, Kitiara wasn’t insisting Laurana come into hostile or even neutral territory to make the exchange but was agreeing to do it in territory controlled by Laurana’s forces.)

And yes Laurana wasn’t technically the Golden General yet during their meeting at the High Clerist’s Tower, but by that point in the war she had already done a great deal of damage to the Dark Queen’s cause. By that point in the story Laurana has killed a Dragon Highlord, wounded a white dragon, led the party that brought back the Dragonlances (which helped to unify the Whitestone nations), provided the testimony that pretty much killed Derek Crownguard’s attempt to take over the Knighthood, crippled Kitiara’s second in command, and used the Dragon Orb which caused the rout of Kitiara’s army and the death of two of her dragons. Now admittedly, Kitiara might not have known about everything Laurana had done, but she definitely knew Laurana crippled Bakaris, and she should have known that Laurana was responsible for the use of the Dragon Orb. (Remember the sequence of events with the Dragon Orb, Laurana calls out a defiant challenge to the attacking dragons then turns and runs into the tower, a few moments later a strange light comes pouring out of the tower and everything goes to hell for Kitiara’s army, then Laurana comes out of the tower looking half dead. It doesn’t exactly take a genius to put two and two together there and realize Laurana had something to do with the strange light that came out of the tower.) Thus, even if Laurana wasn’t the Golden General yet, Kitiara still had enormous reasons to want to kill or capture Laurana in that moment since Laurana had proven herself to be a massive threat to the Dragonarmies, and as such Kitiara deciding not to harm Laurana in that moment when having her dead to rights was a really big deal. From a military perspective, Kitiara 100% should have taken advantage of Laurana’s vulnerability in that moment to neutralize such a major threat, so the fact that Kitiara didn’t do so strongly suggested that she really didn’t want to harm Laurana.

So yes, Laurana read Kitiara wrong, but it wasn’t an unreasonable reading given her past experience with Kitiara, and as such I think its very unfair to call her a moron or an imbecile for that mistake. She made a judgment call that was logical based on her past experience with Kitiara. That it turned out to be incorrect doesn’t mean it was foolish.

And fully agree about personal feelings about plot points. I’m certainly not saying you are wrong for disliking this plot point, indeed I probably hate the Trap plotline far more than you do, albeit for different reasons. I don’t think it was out of character for Laurana as throughout the books she has been shown to be very brave, very compassionate, and very protective of the people she loved, so her facing danger to help someone she loves seems very in character of her to me. (This certainly isn’t the first time she’s faced extreme danger for her friends, and indeed it isn’t even the first time in the Chronicles that someone used Laurana’s love for her friends to manipulate her as Lord Gunthar pulled the exact same trick on her in the last book when he used Laurana’s love for Sturm to convince her to go to the High Clerist’s Tower for him.) Nor do I think any less of Laurana for falling for the trap since I think she had perfectly understandable and logical reasons for her decision, and even in the Trap chapters we still see a great deal of the qualities in Laurana that make her my favorite character (her courage, her compassion, her determination, and her willingness to sacrifice for the good of others are all on full display in the Trap chapters, and the moment where she cuts loose and destroys Bakaris is really satisfying.) My problem with this plot point is that it essentially took Laurana out of the story for most of Dragons of Spring Dawning which I think really hurt the book. (Laurana was the most dynamic and interesting character in the story, so having her benched for half of Spring Dawning left a huge hole in the story.) Thus as satisfying as it was seeing Laurana subvert the Damsel in Distress trope in the Neraka chapters, I still think the Trap plotline as a whole was a big mistake.

Disappointing to hear it ended in a somewhat limp squelch after Sturm’s finale last book. I remember teenage me thinking at the time that the final book wasn’t as spectacular an end as I had expected. Alas! I really wished this series had been a bit more of a war story, but that’s okay I guess. The Blood Sea of Istar did make quite an impression on me though!

Any thoughts on why Lord Soth became such an enduring icon of the series? He’s basically Kittara’s minion the whole series but he completely outshines her in modern memory. I remember him as being creepy but even more of a non-entity than the others. Is there an exceptional additional work I’m missing?

After the Twins Trilogy, are you planning to do more? I never read the Twins books so I’m very curious to see what you thought, but I will confess a massive soft spot for Doom Brigade. I thought that book did a pretty good job of expanding the world in interesting directions, given the whole one-and-done doomed angle the Draconians had.

As always, thank you for the scintillating review! We salute your perseverance and your insights!

Lord Soth is one of those interesting cases where the isn’t a tonne to the character on his first appearance but where the fans really took a shine to him. See also: Boba Fett. Also in fancy armour!

I think Algol sort of nailed here it when he said “the Boba Fett of Dragonlance”. He’s cool, brooding, goth as fuck, and has a tragic backstory — and he’s a practically unstoppable badass. Sometimes all you need is the right character concept to hook people in.

I’m planning to do more Dragonlance, though I might give the Tales anthologies a miss. I don’t relish the idea of reviewing three anthologies back-to-back, so I might just go for The Legend of Huma next. We’ll see how much energy I have.

I’m glad you enjoy it! Thanks for the kind words.

Laurana being a complete idiot during the prisoner exchange could have been avoided so easily. It’s been a while since I read this one, but I don’t think the heroes had any idea about Lord Soth at that point. If Laurana had brought, say, twenty soldiers to the exchange, Soth would still have been able to defeat them (or just frighten them away) and Kitiara could still have captured her without her looking like a gullible, thinking-with-her-heart fool.

Ah, well. Still cautiously optimistic that you’ll like Legends, which I have read recently and which I think is probably the most character-driven D&D fiction ever written.

That’s effectively how the story played out anyway though. Laurana and the bodyguards she brought with her in canon were already sufficient to get her out of the trap until Lord Soth appeared.

And anyway when treating with the enemy, it really comes down to whether they are honorable or not. If your enemy is honorable then meeting them with just a single bodyguard is more than sufficient (as shown by the example of Hannibal Barca safely meeting with Scipio Africanus with each only having a translator with them). If your enemy is dishonorable then bringing a whole host of bodyguards with you might not be enough. (Toussaint Louverture was kidnapped while meeting with the French during a cease-fire despite having one hundred of his companions with him.) Laurana’s mistake wasn’t in failing to bring enough guards with her, it was in trusting Kitiara, and since Laurana did have good, logical reasons for thinking she could trust Kitiara based on her prior encounter with the Highlord, she shouldn’t be faulted for that mistake.

Upon further review, it looks like Toussaint Louverture only had 20 guards with him when he was betrayed and captured, but the point still stands that having a large force of guards with you is not necessarily a protection against getting betrayed at parley.

I look forward to this process arguably even more than Forgotten Realms, since after the first two trilogies, the DragonLance novels seem to be wildly uneven and controversial, with little consensus about the high point (except for maybe a few gems like Lord Toede and Weasel’s Luck). I read precious few of them, so it’ll be interesting to hear your take on it all.

In the fullness of time, will you cycle back to, say, the Penhaligon Trilogy and the other oddball non-series TSR novels?

I don’t know how far I’ll go into the Dragonlance series, since I recall that the quality dropped off pretty severely after Weis & Hickman left. I only remember a few gems in the fifty or so post-W&H novels that I read way back when. And to be honest, I just don’t find Dragonlance to be nearly as interesting a setting as the Realms. Once you get outside of the War of the Lance and the stories of the original heroes, it feels kind of threadbare and empty by comparison. We’ll see how much of it I have the stomach for before I get bored and switch to some other series — maybe the Spelljammer or Dark Sun books? We’ll see.

After some thought, my personal opinion Is that the main issue with two of the pitfalls of this book, the Laurana kidnapping and the Tanis character arc, is the way they were developed by Weis and Hickman rather than problems with the ideas per se.

Tanis has plenty of reasons to be a complete emotional wreck: he has willingly spent three days with a Dragon Highlord, has lied to his friends, has betrayed them telling Kitiara of Berem, doomed all of them in the Maelstrom, including one of the two true clerics of the world, Goldmoon, and the only possibility to defeat the Dark Queen, Berem. I understand why he is so angry with himself to overreact in such a bad way when he discovers to be the not perfect leader he wanted to be. When in Kalaman, he discovered that Sturm has died and Laurana has fallen in Kitiara’s trap because she thought he was dying. During the trip to Neraka, his plan is upset by Fizban and at Godshome he belived that Berem has killed his longtime friend Flint. I cannot blame him for losing his temper and get his revenge. What really doesn’t work Is how easily Tanis wins back his friend’s trust in him. They never seem to doubt his good faith in all his mistakes, nor they seem to be upset when Tanis repeatdly shouts after them and he is ostensibly uncapable of being their leader amy more. I think that it would have worked better if Tanis had to regain Caramon & co trust as a friend and a leader gradually.

As a side note, I realized alzo that Flint’s death works as a character development moment not only on Tas but also on Tanis, because wrongly killing Berem is the bottom point of his downfall.

As for the Trap plotline, Weis and Hickman clearly wanted to create a situation where Laurana kidnapping was somehow Tanis’ fault and how their weak love, as compared to. Goldmoon and Riverwind’s, could have caused the defeat of the forces of good. Thus, having Laurana captured during a fight would not have worked in that way. However, even giving Laurana some excuses for being stressed, tired and possibly intoxicated when receiving Kitiara’s note, the way the whole scene was played out smelled easily of a trap that no general, especially a competent one such as Laurana, whom also clearly demonstrated to be able to put aside her feeling towards Tanis for a better good, would fall into. So, again, the blame is on the authors for conceiving such a forced way to implement the same basic idea (although I admit I haven’t any better solution).