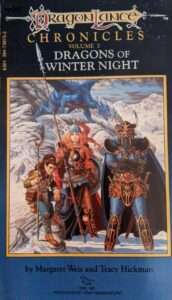

Author: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman

Published: July 1985

This book is in many ways the Empire Strikes Back of the Dragonlance trilogy: an emotional roller-coaster where the heroes gain the abilities they’ll need to defeat the Big Bads in the final segment, but suffer great losses and setbacks in the process, and it ends on a note that’s dark but not hopeless. And like Empire, I seem to recall that it was the best of the trilogy. Does it still hold up decades later, or am I remembering it more fondly than it deserves? Let’s dig in and find out.

As before, since the early Dragonlance books were TSR’s most culturally significant and financially successful novels, I’m going to spend extra time digging into this book piece by piece. I expect this will probably end up being rather longer than one of my usual posts. (Spoilers will abound, of course.)

Plot

To be honest, the plot here is kind of a mess. It starts slow, the characters split up into multiple separate groups, some of the things they do seem pointless, and they spend a fair amount of the story without much agency. That said, at least they’re not being dragged around by the noses by the gods like they were in the previous book, and the last third or so of the book really gets its shit together and tells a compelling story.

For this book, the authors were freed from the constraints of having to adapt the D&D modules beat-for-beat. You can see from the very first pages how that’s improved their ability to tell a story: there’s a dwarven poem quickly summarizing how they went dungeon-delving for a magical artifact (the events of the Dragons of Hope and Dragons of Desolation modules), and then we see the aftermath of their success where the heroes have to decide what to do next. It’s such a breath of fresh air after the long dungeon-crawling sequences of the previous book, since the authors get to focus on things that actually matter to the plot instead of trying to novelize a bunch of D&D sessions. The magical artifact they went searching for doesn’t end up making a damn bit of difference to the story, so the faster we can get that out of the way, the better.

We open in the dwarven kingdom of Thorbardin, where the heroes have bought safety for their ex-slave refugees by restoring an ancient dwarven artifact to its rightful owners. The prologue, where Tanis, Sturm, and Raistlin argue during the celebration, does a great job of foreshadowing some of the main character arcs. Tanis is fallible and vulnerable, with his near-incapacitation from claustrophobia representing how his self-control is slipping. In a small way, Sturm demonstrates his glory-seeking behaviour and willingness to die for the greater good. And Raistlin gets to be kind of a dick, which is appropriate enough for the book where he falls to the dark side.

The book’s opening hook isn’t much to speak of, though. Apparently the heroes want to head to the famous seaport of Tarsis, which nobody has heard from since the Cataclysm three hundred years ago, so that they can buy safe passage for the refugees to… hell, they don’t actually know where. Somewhere else with fewer dragon problems, I guess? Apparently the reason why nobody’s heard from Tarsis in three hundred years is that the mountain range which bisects this part of the continent has prevented communication between its east and west halves for centuries. Guys, we’ve got a perfectly good solution for that problem! It’s called a boat. Just sail around them! I find it hard to believe that nobody’s ever tried to sail down to Tarsis, a famous seaport, in the past three hundred years.

Frankly, it’s hard to care about the whole “let’s make arrangements for the refugees” plot. We’re here for an epic war between light and darkness, not finding a home for a few hundred farmers, so it feels like a make-work excuse to kick off the plot rather than something exciting or relevant. The refugees are already safe in Thorbardin, if not exactly comfortable, so it doesn’t even feel urgent. It’s such a relief when dragons start blowing shit up to get the heroes involved with the war again, but that won’t happen for another six chapters. Not a great way to start the book.

There’s lots of inter-character conflict from the very beginning. Are they doing the right thing by giving away the Hammer of Kharas, the magical artifact they recovered? What should they do with the refugees? Tanis and Laurana are having issues because he can’t admit his feelings for her and she thinks he’s being a cynical bastard. All this arguing and conflict would be grating and cost the characters a lot of sympathy if they weren’t able to put it aside and function as a well-oiled machine when danger arises. It doesn’t impact their competence, so the reader doesn’t get frustrated by it.

This whole section is full of foreboding: the heroes’ actions are known to the enemy, they’re short on hope, and they’re just trying to escape from the war instead of trying to do anything about it. It establishes an appropriately grim tone, but it would work better if it felt like it was going anywhere. And the heroes eventually discover that Tarsis has been landlocked ever since the Cataclysm, when tectonic upheavals caused the shoreline to retreat about 50 miles, so it turns out that this entire subplot has been completely pointless from the get-go.

The narrator then takes us aside to give us a brief history of Tarsis. The authors are still heavy-handedly trying to convince us that the gods nuking the entire the world was a rational response to the upper management of Istar getting uppity, and it’s still not convincing. Modern-day Tarsis is represented as godless, with repeated emphasis on the false beliefs of its people, and it’s a land of misrule where people have become insular and hostile in response to their misfortune. The part about them being bitter towards the Knights of Solamnia for centuries because they couldn’t save everyone from the Cataclysm is just… come on, folks. What are a bunch of knights supposed to do about a gigantic meteor destroying the continent? Wave their swords at it? It feels like an excuse for some contrived conflict.

Fortunately for our struggling plot, the dragonarmies choose the day the companions arrive in Tarsis to conquer the city. But… why? Looking at a map [1] and judging by what we’ve been told so far, it looks like Tarsis is an isolationist shithole in the middle of absolutely nowhere that’s no threat to their plans at all. Don’t they need this army up north, where the real fighting is? This city doesn’t seem to have any resources that anyone wants, and they haven’t been an economic or military powerhouse for a few hundred years, so why even bother?

This is another instance of something that bothered me in the first book and which I’ll probably be complaining about regularly: the dragonarmies feel less like real armies and more like an author-driven force that shows up out of nowhere sometimes to push the plot forward. Real armies have strategic goals they want to accomplish, but the dragonarmies’ goals just seem to be “take shit over and be evil,” and it’s not clear how what they’re doing furthers any objectives. Real armies have logistics, but here the dragonarmies seem to have just teleported past a hundred and fifty miles of barren plain without anyone noticing. We’re told almost nothing about the strength, disposition, or goals of the forces of evil, and the geography of Krynn is often quite vague, so we have no way to know how much of a threat they are in any given region at any given time.

The root cause of this problem is that fantasy authors always want to have epic Tolkien-style clashes of armies, but they don’t know the first thing about how war works. Tolkien had a huge amount of scholarly experience with ancient war and first-hand experience with modern war, so his logistics and tactics actually make a lot of sense. His many imitators tend to have armies that just teleport around, don’t need food or roads or wagons, and attack with tactics that belong in Hollywood movies rather than a real pre-modern setting. Curiously, though, Weis & Hickman will do a much better job with the second big army battle of this book… but we’ll cover that once we get there.

Anyhow, the heroes get arrested and there’s a courtroom scene where Sturm gets to demonstrate his nobility and compassion, contrasting it against the intolerance and suspicion of the Tarsian people. He then meets Alhana, a mysterious elven lady who turns out to be the Silvanesti princess, and they have a real “doomed love at first sight” moment.

No, thought Tanis sadly, the silver moon itself was not higher or farther out of Sturm’s reach.

But the red moon is no problem, right, Sturm? (Rimshot, mug to camera.)

Then the dragonarmies attack, everything goes to shit, and our heroes are split into two groups who won’t meet again for the rest of the book. This is rather a shame, I think. The more separate points of view you have, the harder it is to keep the book’s pace humming along because you keep having to switch between disconnected storylines, and when you have fewer characters in each group you have fewer opportunities for character-developing interactions. But then again, the sheer size of the group which the authors have assembled — thirteen characters, not counting the Knights! — means they didn’t really have a choice. At that point you have to either split them up, write some characters out of the story to get it back down to a manageable level, or accept that some characters are going to be forgotten about in the background.

The authors do the best job they could with it; when the group splits up, they devote lots of consecutive chapters to each group’s story instead of rapidly switching between them, which avoids killing the pacing too badly. I wish they’d ditched some non-essential characters, though. Goldmoon and Riverwind particularly stand out for having absolutely nothing to do and no role to play for the entire book, so I wish they’d been left behind.

The first group we follow (Tanis, Sturm, Caramon, Raistlin, Tika, Alhana, and the two useless baggages) head across the continent to the forest home of the Silvanesti elves, where the elven king thought it would be a great idea to use a dangerous magical artifact to defend his lands. Now he’s been trapped by it in a weird nightmare dream-state that’s making his fears bleed into the real-life forest, turning it dark and creepy. The whole “king using a magical glass orb that drives him crazy” shtick is another Tolkien-inspired shenanigan, but the details are different enough to make it feel like inspiration rather than pastiche. Silvanesti itself, with its bleeding trees and green mists, is a much better take on the “scary forest” trope than Darken Wood from the previous book. It quickly devolves into a surreal sequence of phantasmagoric horrors where each of the heroes has a dream in which they face their deepest insecurities, and most of them “die” gruesomely in the process.

I’m of two minds about this whole subplot. On the one hand, it’s full of good character moments, including one (Raistlin killing dream-Caramon) that continues to affect the plot for the rest of the book. On the other hand, it feels like nothing but character moments, since none of the heroes except Raistlin have any agency in the dream. We mostly just watch them wander around and suffer for a while until Raistlin clobbers the Big Bad at the end. Said villain is the ancient green dragon Cyan Bloodbane, who plays more of a role in the associated D&D module (Dragons of Dreams), but only makes a bland cameo appearance here and could easily have been written out of the plot without losing anything.

At least it’s a solid introduction to an important element of the rest of the novel’s plot: the dragon orbs, a set of magical artifacts that can control dragons. Seeing how badly things go wrong when the wielder isn’t able to control one sets up the stakes for the heroes’ two forthcoming attempts to use them, and it’s good to have macguffins that give the heroes clear goals to follow. Until now the dragonarmies have been invincible, so this book badly needed a way in which the heroes could make a difference instead of following their initial “run and hide” plan.

With the Silvanesti conflict done, we swap over to the group whose adventures will occupy most of the rest of the novel: Laurana, Gilthanas, Tasslehoff, Flint, Elistan, and some random Knights of Solamnia. Once again — hooray! — we start a section of the book by cutting out a long dungeon-crawl (the events of the Dragons of Ice module). It’s summarized by a poem told from the point of view of a bard from the tribal culture of the Icewall Glacier, where they’ve gone to seek another dragon orb. Many scenes of pointless ass-kicking of walrus-men are avoided, and they even kill a Dragon Highlord off-screen. Not only is none of that terribly relevant to the main plot, but it shows the reader that Krynn has other cultures who perceive the heroes in a unique way.

The action picks up with the party taking their newly looted dragon orb by ship from Icewall to Ergoth, the western islands where the refugee elven nations have established their governments-in-exile. I have to call out the great world-building in this section. The Silvanesti and Qualinesti have basically colonized the lands of the indigenous wild elves, the Kagonesti. They’re on the brink of war with each other, they’re angry at the humans, and they don’t give a shit about the Kagonesti, so everything is a simmering powder keg of potential conflict. It shows that some problems on Krynn are way bigger than the heroes, something they have to survive instead of something they can solve while they breeze through, and it’s all deeply rooted in the history of the setting.

It’s a great depiction of colonialism. Even the friendliest of the Silvanesti and Qualinesti elves don’t make any effort to understand or empathize with the Kagonesti; they just use them and ignore them as if they’re beneath notice, effectively enslaving them and making their traditional way of life impossible. It’s a big change from the gully dwarves of the first book — the Kagonesti are treated with compassion by both the heroes and the narrator, so it’s only the other elves who think they’re degenerate barbarians. They’re an object of pity rather than the butt of a joke, which is so much more compelling.

It also sets up a thorny situation which the heroes can’t resolve with violence. The Qualinesti confiscate the dragon orb for themselves, and fighting an entire nation of elves for it would be suicide. Laurana’s father is an obdurate dickhead who’s all “I have no daughter” and refuses to listen to her, giving her lots of sympathetic drama. Derek Crownguard, the only survivor of the Knights who went on the glacier quest with the heroes, is an obstreperous tool whose idea of diplomacy is to tell the elves to go fuck themselves. The elves think Elistan is a charlatan who’s just pretending to be a cleric of the true gods. Basically everything that can go wrong is going wrong, and the only way out is for the heroes to steal the dragon orb and go on the run from thousands of angry elves. It’s a good low point for the protagonists which shows us that they’re on their own; nobody’s on their side at this point and no irritating gods have shown up to fix their problems for them.

Except… then they kinda do. Silvara, a Kagonesti elf who helps them escape, is clearly some sort of supernatural guide type. She’s suspicious as hell, knows all kinds of things she shouldn’t be able to know, and between her name and the legend she tells during their boat trip, it’s pretty obvious what she is and whose side she’s on. But I appreciated the added tension, and I wasn’t too frustrated by the heroes failing to figure it out because it’s more obvious to the reader, with our expectations about storytelling conventions, than it would be for people inside the story. We know that if someone tells a campfire story in a book, it will inevitably turn out to be relevant to the plot somehow — they don’t.

We urgently need some tension in this part of the plot, too, because the flight from Qualimori is a long segment of the book that could have been cut way down. The heroes have zero agency — once the stakes of “what’s Silvara’s game?” are established, there’s nothing they can do but trail behind her, look at scenery, and occasionally announce “Boy, I sure am suspicious!” It’s another long sequence with a lot of character work and little plot development, and this book already had one too many of those. Still, at least Silvara makes a much less irritating supernatural guide than Fizban did in the last book. She’s clearly desperate and limited in her abilities, so it doesn’t feel like she knows everything or has the power to solve everyone’s problems.

Speaking of which, Fizban suddenly returns! Out of nowhere, with no explanation! And immediately starts breaking the fourth wall!

“Was it a nice funeral?” he asked. “Did lots of people come? Was there a twenty-one gun salute? I always wanted a twenty-one gun salute.”

“I—uh…” Tas stammered, wondering what a gun was.

Please stop — I’m trying to stay immersed here. That said, at least his divine interference is much more restrained in this book. He takes Tasslehoff on an adventure and contributes cryptic comments, but he doesn’t do the sort of “gods do everything and give the heroes no choices” crap that we saw in Dragons of Autumn Twilight. That said, I’m still baffled by how low-key his contributions are given that he’s an avatar of Paladine, the chief god of good. When the Queen of Darkness is taking an active role and bending entire countries to her will, why wander about pretending to be a senile old man? It works out for him in the end, but it seems like it could have worked out faster and easier if he’d been more directly helpful and less manipulative.

The heroes now fragment even further. Sturm and Derek buggered off a few chapters ago to take the dragon orb to Solamnia, and now Tasslehoff and Fizban wander off to visit the gnomes while the rest go forge some dragonlances off-screen. It’s not a serious pacing issue, since at least we’re not trying to follow all of them at once, but the problem is that we’re following the characters who are doing things that don’t matter to the plot and ignoring the group that’s actually doing something interesting.

Sturm’s trial, where Derek accuses him of disobedience and cowardice in the face of the enemy, is a great theme-supporting sequence. The fractious politics of the Knights of Solamnia, like the elves’ cold war, show us how the forces of good are divided against each other, and the way they’re locked into empty ritual and tradition without understanding the meaning behind their rules will come up again and again. It’s fantastic character development for Sturm, too, as he faces the very real possibility of losing his chance to become a knight if he does the right thing.

And then we get to Fizban taking Tasslehoff to visit Mount Nevermind, home of the gnomes, which really did not thrill me. I genuinely dislike the gnomes. They’re an entire nation of steampunk mad scientists, creating ridiculously impractical and dangerous inventions to do the most basic of tasks. It’s the same sort of immersion-breaking setting mismatch that you’d get if Coppola had cast Jerry Lewis in Apocalypse Now. They’re not more punching-down losers like the gully dwarves, thank goodness, but they’re extremely silly in an unrealistic way that contrasts badly with the otherwise gritty story — we’re trying to establish some serious stakes here and instead the authors are taking us on a detour through a Dr. Seuss cartoon. Furthermore, the whole Mount Nevermind section has little dramatic tension or impact on the plot, so it just feels like an excuse for the authors to show off some of their worldbuilding.

Fortunately, this is where the story finally starts getting its act together. Representatives of all the various human and elven nations come together to figure out what to do about the war and the dragon orb, and Fizban and Tasslehoff are present to watch the proceedings. The council’s politics are as intractable as they are straightforward: each group has good reasons to disagree with the others, there are assholes on all sides, and the elves’ threat to go to war with the Solamnians to get the stolen dragon orb back makes diplomacy excruciatingly difficult. It’s a great setup for a scene, but it would have been better if the authors had given us more details about the broader situation. Where are the dragonarmies? What are they doing right now that presents a threat? No idea — it’s all left vague.

The dragon orb getting smashed is such a great plot twist. The heroes fought and bled for it, everyone wants it, we’re repeatedly told that it’s the last hope against the dragons, and then Tasslehoff smashes it to pieces because he sees that it’s the only way to avoid losing the war before it’s even begun. Since the council’s stakes have been so clearly established, it doesn’t feel like a shaggy dog story where they spend ages getting the orb and then lose it, shrug, and continue on — it’s a desperate sacrifice for the greater good. And it’s a deliberate decision that fits Tas’ character perfectly, which is a relief after all the railroading of the last book. Then the rest of the off-screen heroes show up with dragonlances and convince everyone to work together.

Meanwhile, we’ve been doing occasional cutaway chapters to what’s been going on with Tanis and his crew since they left Silvanesti, and it turns out to be… not much. They want to bring the Silvanesti dragon orb to the city of Palanthas, but it’s a long boat journey and they don’t have enough money, so they start a travelling circus. Raistlin does elaborate magical illusions, Tika dances, Goldmoon sings, and so forth. It’s cute, showing a bit of what the characters’ lives could have been like if they hadn’t been thrust into heroing, and it’s good character development for Raistlin when he gets a taste of genuine contentment but decides that his quest for power is more important than even happiness, but ultimately it’s a long stretch where nothing much happens. The only major event is Tanis running into his old ex-girlfriend Kitiara, who’s become a powerful Dragon Highlord in the service of the Queen of Darkness, and having a fling with her which demonstrates his inner turmoil and lack of direction.

The reason I haven’t mentioned any of this yet is because it’s basically irrelevant to the plot. By the end of the book they’re still nowhere near Palanthas, and nothing they do (using the dragon orb, finding Berem, meeting Kitiara, etc.) will become important until the next book, so I don’t have much to say about it. There are lots of irritating coincidences, too — how convenient is it that Tanis’ crew take the one ship in all of Krynn where the Green Gemstone Man is working as a sailor? And then Tanis gets ambushed in the one alley that his ex, whom he hasn’t seen for five years, is walking past? Unlike the other plotline, it doesn’t feel like events are happening naturally here.

Anyhow, back to the stuff that matters. Sturm is made a sub-commander of the Knights’ forces reinforcing the High Clerist’s Tower, which guards the mountain pass between the dragonarmies and the city of Palanthas, and Laurana, Flint, and Tasslehoff come along and bring a bunch of dragonlances. This is the darkest point of the novel, where a small force of knights is besieged and starving and expecting to die any minute now at the hands of the overwhelming forces arrayed against them. Things go from bad to worse, with the supply lines behind them closed by snow and Derek’s vainglory turning into genuine megalomania; he gets half the defending force killed in a meaningless sortie, dying in the process. But even when presented with the opportunity to escape, the heroes choose to stay because they’d rather go down fighting than be responsible for the destruction of Palanthas.

This whole sequence, with a handful of demoralized troops besieged by a vastly superior foe and led by a paranoid madman, feels like it owes a lot to the Minas Tirith battle in Lord of the Rings, but once again there are enough differences in the scenario to make it a homage rather than a ripoff. Also, it’s far superior to any of the previous army-related scenes in how it handles logistics. The Knights need to worry about their supply lines being cut off. The dragonarmies use sensible withdraw-and-envelop tactics against the Knights’ sortie. The Dragon Highlord pulls their forces back before the dragons attack to avoid breaking their own lines with dragonfear. For the first time in this series, it feels like attention has been paid to the details of how a military operation would work instead of “Suddenly, an army is here! Oh no!”.

It’s a great opportunity for character development, with each of the heroes finding their own source of inner courage to stay and fight. We get Sturm’s defining character moment, where he finally snaps and tells the Knights to go fuck themselves, and it’s fantastic. His entire character arc for two books has led up to the moment where he realizes that to be a good person, he can’t live within the Knights’ confining framework.

It all comes to a climax in a dramatic attack on the Tower, after the heroes have figured out that its strange layout is because it was designed, centuries ago, to be a trap for dragons. Sturm is killed by Kitiara while giving Laurana time to bait the trap — oh no! How could Kitiara kill her fellow astronaut? [2] His death is a great cap to his character arc, though. I can’t see any way that either a happy ending or a meaningless death would have worked for him — he always needed to die for his principles, and his death shows the Knights the folly of their hypocritical rules and causes lasting change. It’s not merely killing off a character for dramatic impact, but the satisfying and inevitable culmination of a long arc.

Everything else was gone: his ideals, his hopes, his dreams. The Knighthood was collapsing. The Measure had been found wanting. Everything in his life was meaningless. His death must not be so. He would buy Laurana time, buy it with his life, since that was all he had to give. And he would die according to the Code, since that was all he had to cling to.

Laurana manages to activate the Tower’s dragon orb, luring the opposing blue dragons into a deadly trap and scattering the draconians in the opposing army, then has a dramatic confrontation with Kitiara atop the fortress walls. Sturm’s death is used as an opportunity for character development, with lots of time spent on the aftermath of the heroes’ Pyrrhic victory and its effect on the survivors instead of rushing along to more plot beats. By the end, we feel like we’ve witnessed a turning point — every victory for the heroes comes at great cost, but they’ve demonstrated that the forces of evil aren’t unstoppable and that it’s possible to win if everyone works together and doesn’t lose hope.

Characters

One big reason why this novel’s plot feels stronger than that of Dragons of Autumn Twilight is that we finally get some decent villains. The last book had Verminaard, an over-the-top Dark Lord stereotype who got little character development and then died like a chump. In this book we get Derek, a narcissistic shit of a Knight, and Kitiara, the half-sister of Caramon and Raistlin who’s done a wholehearted heel turn and embraced evil out of pure self-interest. Both of them have a human-scale sort of evil that feels compellingly realistic rather than cartoonish.

Derek Crownguard, a high-ranking Knight of Solamnia who leads a powerful political faction, is the very picture of toxic masculinity: argumentative, sexist, insecure, and petulant whenever he doesn’t get his way. He uses constant microaggressions to assert his dominance, like when he praises Laurana’s brother for something she did, and repeatedly demonstrates that he’d let the world burn as long as it meant that people would respect and fear him. He gradually deteriorates under the intense stress of the war, becoming increasingly megalomaniacal and unmoored from reality, and it’s all Sturm can do to keep him from destroying everything in his mad quest for glory. They make a great contrast against each other throughout the entire novel, culminating with Sturm discovering himself and Derek losing himself when under the pressure of imminent death. By the end, we’ve seen their defenses stripped away and gotten a good look at what lies underneath — which, in Derek’s case, is a worthless sociopathic shithead.

Kitiara, whose appearance has been foreshadowed since the very beginning of the first book, also makes a great villain. Her backstory is tied into the other characters (Caramon and Raistlin’s sister, Tanis’ ex, Laurana’s romantic rival), so she comes with lots of ready-made conflicts, and her villainy is the pragmatic evil of someone who’s determined to be on the winning side no matter what. Unlike Verminaard, she demonstrates human qualities — seemingly genuine affection for Tanis and regret at killing Sturm — which makes you wonder if there’s a chance that she might be redeemable. My only qualm is that it feels like a stereotypical bit of moralizing on the authors’ part that Kitiara is assertive, sensual, and worldly, and is evil, while Laurana is chaste, modest, and naive, and she’s good. Still, I can’t complain about having more women in major roles.

Tanis takes much more of a backseat in this book compared to the last one. He’s still the nominal leader of the party, at least before they split up, but he’s lost his moral compass and sense of purpose and doesn’t have much agency. It all culminates in him abandoning his friends to shack up with Kitiara near the end of the book, which is less a decision he makes than the natural endpoint of him gradually rolling downhill. There are too many characters around for his “loss of faith” subplot to get the time and attention it needs, though, so it feels a little anemic.

The real main character for the first half of the book is the sickly mage Raistlin, whose character arc sees him fall to full-fledged evil to satiate his hunger for power. Throughout the first book and the beginning of this book, the other characters have been talking about how there are shadows hovering around him and whatnot, and we see him be rude to his brother, but he’s never actually done anything evil. When he offers to secretly poison Laurana to prevent her capture in Tarsis, that’s the first crack in the façade. He finally crosses the moral event horizon during the dream sequence in Silvanesti, where he saves the party from the nightmare purely out of self-interest and allows his brother to “die” in the dream to fulfill his own ends. From there on out, it’s clear that Raistlin is solely on Raistlin’s side, and to hell with the forces of good and evil except inasmuch as they can serve his purposes.

Again, the authors are doing a good job with the villainy here. His fall is something the reader is prepared for, rather than something which comes out of nowhere, because they’ve been laying the groundwork for it for a while. And he gets several little humanizing moments, like revealing his tragic backstory to Laurana or finding joy in using his magic to entertain people, that make him seem like an actual human rather than a sociopathic robot. It’s a tough line for an author to walk; you want to provide just enough humanity for a character to be believable, but not so much that their evil doesn’t make sense or it feels like you’re trying to excuse their actions.

Most of the good characterization happens in the Sturm-Laurana-Tasslehoff plotline, though. Sturm’s arc is well done, as I mentioned earlier. He’s set up from the beginning to be a tragic figure, and his death is the natural consequence of who he is and the situation he’s in rather than something which just happens to him.

Alhana looked up into Sturm’s grieved face and saw etched there pride, nobility, strict inflexible discipline, constant striving for perfection—perfection unattainable. And thus the deep sorrow in his eyes.

This book sees Laurana get an upgrade from tag-along character to full-fledged hero. Her disastrous homecoming engenders sympathy for her plight, shows how much she’s grown, and demonstrates what a Herculean task lies ahead of the heroes, since all the folks who should be their allies are stiff-necked, fractious assholes. She’s got both talents and flaws: she’s kind-hearted, good in a fight and has an adamant resolve, but she hates being thrust into a position of leadership and doesn’t know how to handle responsibility for others. In the end, she learns self-reliance and leadership the hard way. All things considered, it’s a good mix of vulnerable and badass that doesn’t lean too hard into either.

Her brother Gilthanas gets a similar protagonist upgrade during everything that happens on Ergoth in Book II. In Dragons of Autumn Twilight he was just sort of an unlikable jerk who served as a stand-in for traditional elven culture, but now he’s forced to make difficult decisions and, despite his prejudices, falls in love with someone unsuitable for a prince. He eventually defies his father and his people to do what he knows is right. It’s somewhat spoiled by the last time we see him, though, where he’s heartbroken and destroyed because he’s learned that his girlfriend is actually a silver dragon instead of an elf. It didn’t make sense to me when I first read this as a kid and it still doesn’t make sense to me now, because my reaction would be more along the lines of “That is so awesome! Can you take me flying?” Just get over it and start being supportive, buddy.

Tasslehoff is still a surprisingly great character. The kender seem practically tailor-made to be irritating — their lack of common sense, their carefree indifference to life-threatening situations, their rampant kleptomania — so the fact that I consistently enjoy this character still amazes me. He moves the plot forward not by being a hero, but by simply being a good person in the right place at the right time, which makes him the living embodiment of the trilogy’s theme: small acts of goodness can save the world. His performance at the Council meeting is one of the high points of the novel, and his distress at the dying dragons’ suffering during the final battle is the most touchingly human part of the book. It’s making me look forward to the next trilogy, where I remember that he played a major role.

Theros Ironfeld is an extra from the first book whose only role was to lie on a floor and be injured. He gets some lines in this book, but he’s still not much of a character; I couldn’t tell you anything about who he is, what he likes, what his backstory is, or anything like that. He’s just a shortcut to getting the dragonlances into the story. Still, I appreciate that we see several plot-relevant Black people with speaking lines — Theros, Maquesta, and the Ergothians at the Council — even if they’re not major characters. In just two books, Weis and Hickman have already included more Black people than the Forgotten Realms included in the first… let’s see… thirty-four books. Jesus.

The old dwarf Flint is much less aggravating in this book than he was in the last. He gets less screen time and less of it is pratfalls, which is great — that kind of comedy would have killed the dramatic tension the authors are trying to build during the tense action in the Sturm-Laurana-Tasslehoff group’s plotline. Still, he serves no purpose to the plot and adds only minimally to the other characters’ development, so he could easily have been cut without losing anything.

And then there’s… all the rest. There’s not enough time to give everyone attention, so some characters end up fading into the background. Once again Caramon’s role is mostly just “get pushed around by Raistlin,” with a side order of a burgeoning relationship with Tika. Tika herself gets practically no time at all. Elistan remains basically an extra with a few speaking parts. Goldmoon and Riverwind… honestly, I forgot that they were in this novel at all. They have no relevance to the plot and very few lines, so I wouldn’t have even noticed if they were missing. It feels like the authors just have too many characters and not enough time.

Themes

The main theme of this book is the danger of isolationism. The real world teaches you important lessons, so walling yourself off from it causes you to become stupid. Only people who go out into the world and see how other people live can understand what’s important and have genuine compassion for others.

This comes up again and again. The people of the isolated city of Tarsis are small-minded and mean, the mountain dwarves lock themselves away in their mountain and ignore the outside world, the stubborn Silvanesti and Qualinesti elves are still vainly trying to hide from the outside world even after the destruction of their homelands, and then there’s Palanthas:

It was a soft city—a city of wealth and beauty, a city that had turned its back upon the world to gaze with admiring eyes into its own mirror.

Most of the conflicts in the book are either caused or exacerbated by people who should be on each others’ sides, but aren’t willing to understand anyone else’s point of view or stick their necks out. Sturm even straight-up says it out loud near the end:

Why was I different [from the rest of the Knights]? Sturm wondered. But he knew the answer, even as he listened to the dwarf grumble. It was because of the dwarf, the kender, the mage, the half-elf… They had taught him to see the world through other eyes. […] Knights like Derek saw the world in stark black and white… Sturm had seen the world in all its radiant colors, in all its bleak grayness.

In short, diversity makes you stronger.

There’s another theme running through all of the Knights’ scenes about tradition versus the meaning of tradition. Over millennia, the lesson the Knighthood was supposed to impart to its members — be a good person and help others — has been replaced by adherence to a strict and complicated code that they blindly follow without understanding the meaning behind the rules. But you can’t legislate goodness, and Sturm eventually has to abandon the rules in order to do what’s right.

“Doomed romance” is another theme in this book. Sturm and Alhana, Caramon and Tika, Gilthanas and Silvara, Tanis and Kitiara and Laurana — just about everyone who has a relationship ends up miserable about it for one reason or another. I like it; it adds to the general feeling of gloom that pervades the story.

Writing

The writing here is a little better than the first book now that the authors have had a chance to practice. There aren’t as many comma splices or random exclamation marks, and the point of view doesn’t jump around quite as often within scenes. Looking back, I find that I don’t have that much to say about the craft here.

The authors repeatedly mix up the word “hauberk” with “halberd,” however, and it really gets on my nerves. Apparently this has been broken in every published edition of the novels — how can it be that no editor has tried to correct this in the past forty years? Looking online, it’s clear that I’m far from the first person to notice this.

The sight of the woman making a gallant effort to rise proved too much for the knight. He took a step forward, and found a hauberk thrust in front of him.

That’s, uhh… not nearly as threatening as you think it is.

There’s a lot of poetry in this book, even more than in the last, and the quality is still generally quite high compared to the usual dismal standard of poetry in fantasy novels. Sometimes it goes way too overboard and disappears up its own ass (“Ascended through hierarchies of space into light”? You have got to be fucking kidding me), but mostly it’s evocative and sells the mythic feel of the subject. Twice it’s used to summarize the events of long dungeon crawls by having another culture recite an epic poem about the heroes’ quest, and seeing how our protagonists look from the outside to other people is a great way to sell their heroic qualities.

Conclusion

Grade: A–

It starts slow and has plenty of nonsense in the middle. Around the halfway point I was beginning to wonder if my positive memories of this book were complete fabrications, because it hadn’t done much to wow me thus far. But once I got to the last third or so of the book, where the authors finally got their act together and brought their A game, I couldn’t put it down. From that point on, it’s remarkably good and it leaves a powerful impression that lingers well after you’ve finished it. I’d say it beats the last book by a fair margin.

I think the major reason why the early parts of the book don’t work as well as the later parts is the sheer size of the party. There are thirteen characters who set out from Thorbardin at the beginning, and that’s a massive boat anchor that drags down the book because the authors spend lots of time on characterization at the expense of giving the heroes agency or fleshing out the world. The seven-person group led by Tanis makes basically no impact on the overall plot, so it’s only once they get sidelined and we start spending time with the Sturm-Laurana-Tasslehoff group that the book really kicks off. That’s a smaller set of characters, so there’s more time to spend with each one, and they’re doing things that actually matter: preventing war between humans and elves, rediscovering dragonlances, fighting off a siege, et cetera. Meanwhile, Tanis and Co. are setting up a travelling circus and wandering the countryside, and nothing they do becomes relevant until the next book.

I know that Weis and Hickman didn’t have a lot of choice in the matter, shackled as they were to the D&D module material, but the lesson here for future authors is simply this: kill your darlings. Centre what matters and ruthlessly trim the things that don’t. I’m not saying that every single scene needs to further the plot — it’s important to have low-tension breaks for fleshing out the characters, setting, and themes — but ultimately everything needs to serve the story’s throughline, the sense that events are progressing towards something rather than just being a random series of happenings.

Soon I’ll tackle Dragons of Spring Dawning, the final book of the trilogy. I remember that it felt a bit mid coming on the heels of this book’s strong conclusion, but we’ll see if a thirty-year gap will change my opinion. Stay fresh and be kind to each other, y’all.

Footnotes

[1] One thing that’s always bothered me about Krynn is how obvious it is, when you look at a map, that it was created on hex paper. Mountain ranges, rivers, shorelines, everything — all of it tends to be oriented in one of the six cardinal directions of a horizontal hex layout. Doesn’t do the world’s verisimilitude any favours.

[2] I know I’m belabouring the “Sturm goes to the moon” jokes, but it’s really the perfect exemplar for how the Dragonlance series lost its way once Weis and Hickman were no longer around. I don’t remember Darkness and Light being a bad novel, per se, but the change in theme from “finding hope in a dark, war-torn world” to “let’s go have Jules Verne-style steampunk adventures on the moon” will never stop being hilarious to me.

After following this blog, I’ve noticed a couple of things about our esteemed host:

1) He’s really, really bad at reading calendars. Christmas is only supposed to come once a year, and in December!

2) If he’s trying to convince me he’s not really Santa Claus in disguise, he’s doing a really, really bad job.

Now, onto other business…

-Our esteemed host reminded me of how people will keep listening to a fat idiot who’s been repeatedly proven wrong because he tells them what they want to hear. Regarding the Tarsians being such dicks to the Knights, I’d remind our esteemed host of how many times people will stubbornly continue blaming other groups for all kinds of urban legends and fairy tales despite having pretty much zero evidence. Just look at the accusations lobbed at groups ranging from the Jews to the Romani over the years. (Gee, maybe the whole reason so many Jews are bankers is because they were blocked from so many other professions for centuries? And why does anyone hold Jesus’s crucifixtion against the Jews when His death and redemption is the whole f*cking POINT of Christianity?!?)

-As a little kid, I was really, really annoyed when the Hammer quest and the journey to Icewall were both cut out of the book proper. I felt like I was getting cheated out of half the story, especially since I actually liked the dungeon-crawl sequences of Autumn Twilight. But, beyond the gaming strictures our esteemed host decried, I should admit that W&H only had so many pages to work with. I can’t remember where I read it, but Margaret Weis apparently said they had a couple hundred pages of the Thorbardin sequence written out, but they had to be cut for space.

The Lost Chronicles novels, which actually show what happened in those parts of the saga, also give the original Chronicles more context. In Dragons Of The Dwarven Depths, Sturm wanted to take the Hammer of Kharas to reforge the dragonlances and be hailed as a hero in Solamnia, going so far as to work with Raistlin to magically trick the dwarves with a fake. Flint, meanwhile, struggled with the old hatreds between his Neidar clan and the other dwarves and the greater good.

Meanwhile, Dragons Of The Highlord Skies shows how Kitiara and Laurana actually meet in person during the invasion of Tarsis, and even explain why the Dragonarmies attack it. Namely, the red dragons want to constantly rape, pillage and burn, to the point where Toede attacks Tarsis because he’s afraid they’ll turn on him. Kitiara flips out when she realizes Toede’s plans, raising some of the same objections our esteemed host did. The red dragons’ short-sightedness is a plot point in Dragons Of The Hourglass Mage, where it’s revealed that even Ariakas has to let his red dragons burn his conquests so they don’t turn on him, but this leaves him short on cash late in the War. Kitiara, meanwhile, tries to govern her conquests sustainably and milks them to fund her next campaign.

-As for Tarsis itself, the sourcebooks indicate that Tarsis is actually one of the main commercial and political hubs of the region. Takhisis wants everything, so sooner or later she’d want this part of the world conquered too. It also has fleeing Silvanesti refugees the Dragonarmies want to genocide, along with the ports that facilitate trade with northern lands like Solamnia. Derek Crownguard and the other Knights the companions meet in Tarsis actually traveled to the port of Rigitt by ship and then hiked overland to the city. (How to explain all this without a massive infodump is something I’m still trying to figure out.)

As to why the Heroes of the Lance didn’t know this, I suppose all we can say is that they never heard much about Tarsis in any of their travels further north. (shrug)

-As before, we see how the 1st Edition tendency for large parties complicates any attempts to novelize a module. The Knights round out Laurana’s party when they’re separated from Tanis’s party, while Tanis’s party is rounded out by Alhana and then some other characters we won’t meet in the novels.

-I agree with our esteemed host’s assessment of the Nightmare chapters. All the character moments are cool (and most are very similar to the fates the heroes suffer in Dragons Of Desolation), but as our esteemed host noted Raistlin is almost the only one who actually accomplishes anything. The rest of the party are just along for the ride, including the ones dragged into the dream…

…although I’m baffled as to why Gilthanas apparently didn’t follow them. Elistan I can understand, but Gilthanas doesn’t even have enough attachment to Laurana to be pulled in?

-Our esteemed host speaks for me about the Mount Nevermind sequence. I couldn’t understand how, if nothing the gnomes made ever worked right, how they even managed to have the basic necessities of life without starving to death, killing themselves or blowing up Mount Nevermind.

-Sturm’s trial is really good too, but I always found it a bit suspect that Gunthar somehow managed to convince the other leading Knights to allow Sturm into the order, especially with Derek’s slander. My own Dragonlance ‘retelling’ has Aran Tallbow and Brian Donner both surviving Icewall and speaking up on Sturm’s behalf along with Laurana and Gilthanas, both strengthening Sturm’s case and making Derek look really bad, which plays into the final sequence (more on that later).

-The really disappointing thing about Tanis’s party is that, after the Nightmare sequence, they don’t really do much of anything while Laurana’s party actually gets shit done. They find the dragonlances, they discover the second dragon orb, they free the good dragons from their Oath, they lead the defense of the High Clerist’s tower. Meanwhile, Tanis and company don’t get to do any of the cool stuff they can in Dragons Of Faith, ranging from breaking up an ogre alliance to saving Berem from Kitiara’s attempts to kidnap him to helping the sea elves fight the undead armies of a demonic sea-monster and help Maquesta become queen of the pirates. I like to imagine Tanis’s party’s efforts seriously fucking up the Dragonarmies’ logistics, which helps Laurana’s party actually lead the fight against them.

-I still remember when I read about Sturm’s death, where it happened, and the thoughts that passed through my head. I was thinking that “wait, this isn’t supposed to happen!” and I suspect made me generally very loath to kill off many of my own long-standing characters in my fanfiction. It makes me wonder about how a dramatic death is foreshadowed…and then something suddenly happens so the doomed character ends up surviving.

I imagined Sturm being ready to sacrifice himself, and Kitiara raising her spear…but then she shifts the angle and throws it past Sturm to impale Derek, who’d gone completely nuts when Sturm, Aran and Laurana forced him out of command and tried to murder Sturm. Sturm is shocked at this, even moreso when he sees who’s under the Highlord’s mask, but she turns and leaves since she realizes the battle’s lost. That isn’t the end of Sturm’s story, though…

Or, as another example, take Spider-Man successfully saving Gwen Stacy when the Green Goblin tosses her off the bridge. I know that scene is iconic…but it’s what everyone expects and often seems to happen, to the point that I decided to mess with the readers’ expectations.

-The thing with Tasslehoff is that, as much as kender seem deliberately designed to give the rest of the gaming table fits, he’s actually useful most of the time. I think this is what a lot of people, both gamers and writers, probably don’t get about kender. Most players just play kender to derail the game, with the “it’s what my character would do” BS as an excuse.

-I didn’t understand what Tanis saw in Kitiara 30 years ago, and I still don’t. Leaving aside the problematic reasons I originally disliked her (her promiscuity and thinking she wasn’t even that attractive because of her boyish haircut-I thought this 30 years ago!), she shows herself to be a manipulative, backstabbing, selfish asshole who’d be just as likely to plant a knife in your back as a kiss on your lips, without any real redeeming qualities that I could discern.

-On the other hand, the character work involving Raistlin is superb, especially as it shows a struggled between his better and worse halves, only for him to fall into the abyss. It’s a nice bit of symbolism that he started out wearing the Red Robes, representing the balance of good and evil, only to change to the Black Robes as both his power and hubris increase to the point where he nearly…well, I’ll save that for when we get to the Legends series.

-Ugh, Sturm and Kit going to the moon with a bunch of tinker gnomes on a steampunk ship. Weis and Hickman actually make a sarcastic reference to this in the Brothers Majere duology that describes Raistlin’s and Caramon’s youth in Solace. Sturm seems to get the short end of the stick in novels not written by W&H-Oath And The Measure involves a lot of divine figures leading him around by the nose and giving him little real agency, even as he usually only survives his dangers through deus ex machina. He also largely fails at his main goal and needs that same divine figure to finish the job for him.

Regarding the Tarsians being such dicks to the Knights, I’d remind our esteemed host of how many times people will stubbornly continue blaming other groups for all kinds of urban legends and fairy tales despite having pretty much zero evidence. Just look at the accusations lobbed at groups ranging from the Jews to the Romani over the years.

Sure, but the key element in prejudices like that is that they always punch down. When it comes to popular scapegoats, you don’t turn on the powerful noblemen with swords and private armies — you turn on the little people who can’t fight back. That way, the bigots can have a satisfying Five Minutes’ Hate and feel like they’ve accomplished something without having had to risk their lives or overturn the social order.

Regarding the Lost Chronicles novels coming along later to try to fix up some of these plot holes… I mean, I’m glad they noticed them and tried to fix them later, but all I can do is review the book that’s put in front of me, and from where I’m presently standing things like the dragonarmies suddenly teleporting into Tarsis look like plot problems. And as for the sourcebooks saying that Tarsis is a commercial hub of the region, I roll to disbelieve. It’s in the middle of the Plains of Dust, which is apparently a vast Gobi-style desert/badlands region. There’s bugger-all around it — no natural resources, no geographically convenient trade routes, no arable land, no large population centres — so I can’t see how it could be a thriving city, and it’s explicitly described in the book as such a shithole that they don’t even have the manpower or resources to get rid of the stranded boats or the huge amount of centuries-old wreckage in the centre of town.

The Thorbardin stuff deserved to be cut, since it had zero relevance to the trilogy’s overall plot. Once they leave Thorbardin at the start of this book, nothing the protagonists do will have anything to do with their time there. I can understand the feeling of “missing out” on content, but not if it’s going to be a completely irrelevant side story.

…although I’m baffled as to why Gilthanas apparently didn’t follow them. Elistan I can understand, but Gilthanas doesn’t even have enough attachment to Laurana to be pulled in?

No kidding. And how did Kitiara get pulled in, anyways? We’re told that Sturm, Tas, Flint, Laurana, and Elistan got pulled into the dream because of Sturm’s connection to Alhana through the Starjewel, but Kitiara didn’t have any magic elven artifacts and wasn’t geographically anywhere near at the time. It’s never explained, at least not in this book.

Sturm’s trial is really good too, but I always found it a bit suspect that Gunthar somehow managed to convince the other leading Knights to allow Sturm into the order, especially with Derek’s slander.

Yeah, that got on my nerves too. I tried to look for an angle where it would somehow benefit his enemies — for instance, is it possible that they were giving him command of the Knights of the Crown at the High Clerist’s Tower to get him killed? But if that were the case, they wouldn’t send Derek and Alfred along with him. I’ve got no good explanation. I could make up some sort of headcanon to explain it, but it doesn’t make sense based on what’s actually in the book.

You’re not wrong about Kitiara having no redeeming qualities, but she spends fairly little of this book on-screen, so the depths of her depravity are only hinted at. The real “moral event horizon” moment for her doesn’t come until the next book, when she demonstrates that she’s willing to kill her brothers.

Sure, but the key element in prejudices like that is that they always punch down. When it comes to popular scapegoats, you don’t turn on the powerful noblemen with swords and private armies — you turn on the little people who can’t fight back. That way, the bigots can have a satisfying Five Minutes’ Hate and feel like they’ve accomplished something without having had to risk their lives or overturn the social order.

Also, scapegoating is usually done to figures who actually have some presence in society. AFAICT, nobody in Tarsis has seen a Solamnic knight in at least a century. It’d be hard to keep a serious hate on for an entity that’s not around and is becoming pretty fuzzily remembered.

And how did Kitiara get pulled in[to the Silvanesti nightmare sequence], anyways?

I don’t get the impression — although it’s been a long time since I read the book — that Kitiara herself had the Silvanesti experience. We know both the main parties did: the ones who were actually there were there, and the Sturm crew has a whole “what a horrible dream!” bit of dialogue making it clear they actually experienced it. Did Kitiara have some post-dream dialogue (with Tanis or somesuch) indicating that she was there and remembered it? ‘Cause otherwise it’d make sense she’s just a tormenting illusion, part of the nightmare, and there’s no need to explain how Kitiara’s own consciousness got pulled in, because it didn’t.

Double-checking… aha! You’re right. She and Laurana talk about the dream, but she had it described to her by Tanis rather than experiencing it directly, so the “Kitiara” in the dream must have been one of the illusions. That clears it up.

Sure, but the key element in prejudices like that is that they always punch down. When it comes to popular scapegoats, you don’t turn on the powerful noblemen with swords and private armies — you turn on the little people who can’t fight back. That way, the bigots can have a satisfying Five Minutes’ Hate and feel like they’ve accomplished something without having had to risk their lives or overturn the social order.

The problem I have with the concept of “punching up/down” is that it isn’t always clear which way is up or down in the first place. For example, academics, artists and activists do not necessarily have a lot of monetary capital, but they often have a lot of cultural capital that can express itself in various ways. Is criticizing or satirizing them when they go too far in the critic’s/author’s opinion always going to be punching down?

To bring it back to Dragonlance, exactly how much capital, cultural or otherwise, does Sturm actually have in Tarsis? The Knights had no real power or authority in Tarsis after the Cataclysm, so despite being aristocratic and powerful on paper, in practice they were easy punching bags for the Tarsians. And it doesn’t change the fact that they indulge in the same BS real-world groups do when they punch down.

And as for the sourcebooks saying that Tarsis is a commercial hub of the region, I roll to disbelieve. It’s in the middle of the Plains of Dust, which is apparently a vast Gobi-style desert/badlands region. There’s bugger-all around it — no natural resources, no geographically convenient trade routes, no arable land, no large population centres — so I can’t see how it could be a thriving city, and it’s explicitly described in the book as such a shithole that they don’t even have the manpower or resources to get rid of the stranded boats or the huge amount of centuries-old wreckage in the centre of town.

After reviewing the sourcebooks again, I realize I overstated my case. Tarsis is a commercial and economic hub for the dirt-poor Plains of Dust, even if it’s a dump by the rest of Ansalon’s standards. And there is some trade that happens of things like peat and furs-and as a Canadian I can tell you the fur trade was lucrative enough to last for centuries up here and play a major role in the country’s European settlement. It’s obviously not as big in the Plains, but there are still multiple settlements and trickles of economic activity here and there.

Of course, as our esteemed host notes all he has to work from is the book as presented, and I don’t recall W&H describing much of the Plains outside of Tarsis itself.

One more point I forgot to mention in my first commentary…

-Several years ago, some writers for the Tor Books website did a chapter-by-chapter review of the Chronicles series. One theme that they remarked on in Dragonlance was how large organizations often proved to be incompetent or even powerless to deal with the Dragonarmies, while it was individuals like the Heroes of the Lance who actually advance the cause of good. In the first book, the Seekers were helpless against the Dragonarmies. In this book, the Knights’ doctrines and beliefs have ossified into a paralyzing bureaucracy that has them bickering over procedural matters instead of properly organizing a war effort, while the Qualinesti are ready to go to war with them over the dragon orb.

It’s an amusing touch of metacommentary that the Chronicles are based on a D&D game where organizations in general are often unable to fully solve problems and depend on small bands of determined individuals to save their necks.

The fur trade in the Americas was lucrative because it was exporting what were luxury goods to European markets, though (and then rich East Coast markets as you get into the 19th Century). Tarsis sure doesn’t seem like it has, or could have, any rich, far-off trading partners looking to them to supply goods they couldn’t get anywhere else – heck, Abanasinia makes way more sense as a center of that kind of trade, given its climate and access to waterways, so if anything you’d expect the Heroes to be dimly aware of traders coming up from the impoverished south to try to get a better price for their goods!

For what it’s worth, it is mentioned in Dragons of the Highlord Skies that Gilthanas did get pulled into the Dream as well.

Oh cool, just catching up on your Dragonlance posts!

I haven’t gone back to reread the Chronicles, but it’s nice to see that my memories seem more or less right; this book was definitely the highlight, with the Whitestone Council and High Clerist’s Tower sequences still standing out decades later. And yeah, while Raistlin was compelling throughout, nothing the eastern party gets up to post-Silvanost feels all that interesting (honestly, I feel like that continues into the next book as well, though partially that’s because the dude-with-a-gemstone-on-his-chest MacGuffin plot is very weak, and as a result everything setting it up likewise comes off as inconsequential).

I agree that the grudge against the Knights seems unlikely to have persisted the way it did — though I suppose unlike Istar and the gods, they stuck around — though I thought the “they could have stopped the Cataclysm!” thing was pegged to Lord Soth? Has he been introduced yet, or does that come later on? Being pissed at him, and by extension his class, seems reasonable enough, though I forget how widespread knowledge of his whole deal would have been.

It’s funny, I’ve been going through the ACOUP archives lately so I smiled when I saw you link to them. The treatment of battles does feel fairly arbitrary throughout the Chronicles, again with the exception of the High Clerist’s Tower (it felt to me like that sequence has more of a debt to Helm’s Deep than Minas Tirith, though I can see your point — and it’s an illustration of the way that Dragonlance often does *just enough* to remix Tolkein to not feel like a direct rip-off). I remember the modules tied into AD&D’s mass combat rules, Battlesystem, which never really caught on; curious whether the game handled this stuff any better.

Finally, not to be a pedantic nerd (he says, preparing to be a pedantic nerd) but I think most of the poetry in the Chronicles isn’t by Weis and Hickman, but Michael Williams, who later wrote the Weasel’s Luck books. I also remember it being a nice way of summarizing the events they were glossing over, especially the glacier-walrus man stuff; I may have written some attempts at imitation when I was a tween, thankfully now lost to the mists of time!

Lord Soth doesn’t get introduced until the third book. In this book it’s just framed as “they thought the Knights, being pious, could have convinced the gods to relent, and were murderously disappointed when they could not.”

Looking at the Battlesystem rules, I can see why it didn’t catch on. It’s a very Gygaxian sort of ruleset — complicated, arbitrary, and full of acronyms. I’ve done some tabletop wargaming in my time, but Battlesystem does not tempt me in the slightest.

You’re right — I should really have credited Michael Williams with the poetry in my posts thus far. I’ll go back and edit that in.

Hello! I’ve been loving all the reviews you’ve been doing on this site and I am thrilled to see you dive into Dragonlance. Keep up the good work! I’ve picked up several of the FR books on your recommendation and haven’t been disappointed yet!

Regarding the halberd/hauberk debacle, I think it gets lampshaded in a later edition? I seem to remember a line where Flint grumbles “back in my day we called them hauberks not halberds”, but maybe I’m hallucinating?

I absolutely adore Sturm’s whole arc. He’s literally too precious for this world… and the authors take him out of it. And the whole battle sequence! *chef’s kiss*

Thanks for the reviews! Continuing to watch with avid interest.

Thanks for the encouragement! I’m glad this is bringing you some joy. You won’t have to wait long for the next one, I hope; I’ve already started working on the final book of the trilogy.

I wouldn’t be surprised if they did such a callback in one of the later Dragonlance books — it wouldn’t be the first time they did something self-referential like that.

Now that I think about it, they did it in Dragons Of The Highlord Skies, one of the Lost Chronicles. Flint is rather embarrassed at calling a halberd a hauberk, but Sturm makes something up that allows him to save face. Brian Donner, one of the Knights who accompanied Derek to Tarsis and died at Icewall, is impressed with the bonds the Heroes share.

Thank you very much for your reviews, they are amazing for being able to wrap up so many things in a limited space.

In the tor.com re-read of the Chronicles, the authors set up a dichotomy between “Team Tanis” and “Team Raist”, since they were the two most popular characters of the saga. However, both the authors and the readers were very harsh on Tanis and his everlasting doubts between Laurana and Kitiara, at the point he was defined as having an “emo” attitude. As a teenager, I always have liked more the shades of grey in Tanis rather than the wizard hungry for power that is destined to fall to the Dark Side, although Raistlin is a great character, such as Tanis, Tas, Sturm, Kitiara and Laurana. It’s a pity that the others are relegated to the background for the majority of the time (Goldmoon and Riverwind fall out of focus very soon, Flint is used as a comic relief, Gilthanas is put out of the story when he starts to be interesting in his relationship with Silvara).

Amyway, the more I ready the Chronicles, the more I am convinced that the best character is Laurana, who starts as a spoiled elven brat with a childhood infatuation for Tanis to the Golden general, with mature feelings. I would like ti know our host’s opinion on that. Great work, again!

I’ve just read a fair amount of the article series you mentioned. While they’re very well written and I agree with the authors on most points, I think they’re being too harsh on Tanis right off the bat. “Emo” is a particularly dismissive way to describe someone dealing with emotional problems, implying that they’re being whiny or over-dramatic, and I don’t think any of that describes Tanis at this point. Getting ghosted by one’s partner, having to break up with someone, and returning home to a place where everyone hates you should be things that cause one distress — not to mention the war! And I think that his long-term character arc, where he starts as the cool-headed, competent one (“We’ll have to go out through the kitchen”) and then undergoes complete emotional collapse and has to crawl out of it again, is quite good in concept. They’ve done a decent job of it with the first two books, but I was disappointed with how it turned out in the third book — more to come on that in the next review. But you’re right that a perfect hero is much less interesting than someone who’s messed up and shades-of-grey, but does their best anyhow.

I agree that Laurana has possibly the strongest character arc of any of the heroes, except for a big chunk of Dragons of Spring Dawning where the authors make her act out of character like a complete idiot in order to further the plot. Even all these years later, I remember how much that irritated the living hell out of me when I first read these books.

(That said, the authors of that tor.com series won me over with the immortal line “This chapter is full of Sturm and dragon, signifying nothing.”)

Speaking about Laurana and Kitiara, my impression is that the Dragonlance saga was atypical for a fantasy novel from the 80ies in the portrait of two very strong female characters, which end up being the leaders of the respective faction. In the meantime, the male protagonists, Raistlin and Tanis are not defined by their role in the war, but rather by their inner conflicts and evolution. Add to it that Goldmoon is the chosen for bringing back the true Gods…

Laurana may have been the very first instance of a good aligned female character commanding an army in speculative fiction. (At the very least I can’t think of any examples before her.)

You may well be right! I can’t think of one either — the only other candidate that springs to mind is from 1988. If anyone out there has a better grounding in 60s–70s era fantasy and can think of an example, I’d love to hear it!

It’s close, but Ce’Nedra in The Belgariad manages this feat in a book published in 1984 – Castle of Wizardry.

Ooh, nice find! You’re quite right.

I’ve been lurking on your blog for a long time – my own formative reading experiences were mostly pulp fantasy, and I’m now a literature professor. So I really appreciate the seriousness with which you approach what a lot of my colleagues still consider throwaway material.

Well, as one of the commenters on this blog once astutely pointed out: “The point of the line between ‘low’ and ‘high’ art likely has a lot more to do with flattering cultural elites than anything else.” Everything that goes into your brain changes who you are to some degree, which is what makes it worthy of study.

Too true! I teach a Sci-Fi and Fantasy course that routinely gets high enrollment, and I’m working on a book about fantasy lit and English identity.

Damn, that sounds awesome! If you want a beta reader once you’ve got a first draft done, hit me up sometime.

Are you familiar with the work of the Welsh Marxist literary critic Raymond Williams? His ethos is much more ‘bottom-up’ than ‘top-down’ in that he starts from two basic premises: first, that culture, whether ‘high’ or ‘low,’ is for everyone, and that everyone’s culture matters and is worth studying. You would probably dig it.

I have not, but I’ll check it out! Thanks!

I enjoyed your commentary, and I wanted to add some points:

– Laurana parents are more complicated that just “I don’t have a daughter”. We get a glimpse into his father’s mind (mother is barely mentioned, except for being ill), and we find that:

* He thought Laurana and Gilthanas had died in Pax Tharkas, to cover the elven nation retreat, and was crushed by it.

* He isn’t a bad person. I think raising Tanis in his own palace shows it. He was even glad to see him in the first novel.

* He thought Gilthanas had died like a hero, but seeing his favourite spoiled kid (Laurana) fleeing home to follow a bastard adventurer was deeply ashaming. Sort of having your Catholic-nuns’ educated girl fleeing home to follow a promiscuous band drummer for a tour.

* According to elven laws, Laurana is still a minor during the second book.

* When he meets her daughter in Ergoth, he weeps, and is willing to “forgive” her. In a sort of “nothing happened, you’re back home now”. But trying to keep her away from social critics.

* He is willingly blind and deaf to anny attempt from others (Flint, Sturm, Gilthanas) to explain him that Laurana is now a grown woman and a capable adventurer. In a fit of anger, he almost calls her a “prostitute”, but restrains himself. He regrets it.

* Curiosly, despite clearly having some perjuices against humans, he is almost convinced that Elistan is the real cleric thing. In fact, Elistan remains with the elves to keep spreading his faith. In the White Stone council, Elistan is something like a counselor of the elven king.

* In the first novel, the elven king hand was burned when he touched the blue crystal wand. If that’s a sign of “sin”, maybe ha had convoluted incidents in his past.

I think that Laurana family was reflected in a very realistic and credible way.

Laurana’s father makes a late attempt of reconciliation during the White Stone event. But he is cleary a shadow of himself, and dies a few years after. Tanis cames back from his funeral at the beginning of Trial of the Twins (Laurana didn’t came, so clearly and sadly they didn’t amend things).

Not being myself a native English speaking person, I’m glad to being corrected in case of commiting mistakes.

Your English is fine! No worries. I quite liked the way that the authors handled Laurana’s relationship with her father, which you’ve summed up here: it starts out complicated, remains complicated, and is never given a happy ending. Their relationship ended up being another casualty of the war, and you can’t have drama without lasting consequences.

@ Roger:

While most of your summary of Laurana’s father is fair, I do disagree with a few points.

-On him not being a bad person, trying to hijack the Dragon Orb from the victims of a shipwreck is a pretty scummy thing to do. That’s straight up piracy. And while he was ok with Tanis being raised in his home, that only lasted until Tanis and Laurana started showing signs of being attracted to each other; at which point he very much wanted Tanis gone. (Of course the irony of it is if Solostaran had actually accepted Tanis as a son rather than as merely a ward, then Laurana would have grown up, seeing him as her brother, and she never would have fallen for him. Solostaran’s own actions in keeping Tanis at arms length from his family was what made it possible for Laurana and Tanis to fall in love with each other.)

-On him being willing to “forgive” Laurana, I’m not sure that’s entirely correct. Here’s the relevant quote:

“Even her parents’ manner was cool and distant after their initial emotional welcome.”

-Dragons of Winter Night, Book II, Chapter 3

That sounds a little meaner (and much less forgiving) than “nothing happened, you’re back home now, but I’m going to keep you away from social critics.” Solostaran only really seems to soften towards her at all after the “human whore” debacle where he feels guilt for having publicly insulted her.

As for whether or not Laurana and Solostaran ever reconciled, Laurana actually was at his funeral. Here’s the relevant quote.

“Laurana’s in Qualinesti now, attending the funeral of her father and also trying to arrange an agreement with that stiff-necked brother of hers, Porthios, and the Knights of Solamnia.”

-Time of the Twins Book I, Chapter 2

Thus, I like to think that Laurana and Solostaran did reconcile after the war. (The fact that the elves returned Wyrmslayer to Tanis at his wedding to Laurana would seem to suggest they did, as I don’t think Solostaran would have allowed a Qualinesti artifact of that importance to be given to Tanis if Solostaran hadn’t reconciled with Laurana and accepted her love for Tanis.)

As far as I can tell what Tanis sees in Kitiara is that she puts out. Which again brings us back to that problematic “worldly woman = evil woman” shorthand

I think the fundamental challenge is that Kitiara spends so much time off-screen that the authors have very little time to characterize their relationship. So yeah, when Tanis reminisces about her it usually involves him remembering how they used to bang, which is a convenient shorthand for “torrid love affair” but doesn’t really explain what makes them connect.

There could potentially be something interesting there if they had gone for “Tanis likes driven women who know what they want” that could then contrast passive Laurana with Kitiara and then as Laurana becomes more actualized during the war explains his shift in affections, but that’s all, like, Marvel No-Prize explanation rather than anything actually on the page, I think.

@100FloorsOfFrights

Did Ce’Nedra actually make any command decisions? I thought she was purely a figurehead.

It’s the best book of the Chronicles. Here’s my rankings for the trilogy.

Autumn Twilight: A

Winter Night: A+

Spring Dawning: B+

With Legends, it’s the best fantasy book series ever. NOTHING can beat Raistlin’s storyarc.