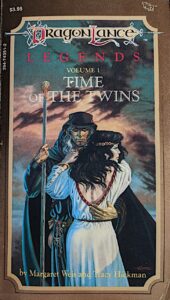

Author: Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman

Published: February 1986

This, the first novel in the Dragonlance Legends [1] trilogy, was published a mere five months after Dragons of Spring Dawning wrapped up the story of the War of the Lance. But the authors clearly had planned ahead for the sequel, leaving themselves plenty of hooks with which to kick off the next series. I found Spring Dawning a bit underwhelming; did their writing abilities improve enough to impress me in the short space of five months?

Surprisingly, yes! Absolutely. I’d say that Time of the Twins beats all of the Chronicles novels by a wide margin, and is one of the better books TSR ever published. I was particularly looking forward to this one, since I think it was the second TSR novel I ever read as a kid and the nostalgia trip seemed like fun, but I didn’t expect that it would still hold up all these decades later.

Characters

Let’s change things up and talk about the characters first, since this is a much more character-focused trilogy than the previous one.

It is such a relief, after the giant eight-to-thirteen-person parties of the previous trilogy, to read a novel that picks a small number of characters (four, mostly) and does a deep dive into their emotions and complicated interactions. That’s not a slam against the authors — they had no choice in the matter, and the Chronicles books did about the best job they could by giving a little character development to everyone and setting up interesting interpersonal dynamics. But ultimately they just had too many balls in the air, and some characters ended up with anemic arcs or got forgotten about completely. I think it’s inevitable with a group that size in a series of small mass-market paperbacks.

Here the crux of the story is the twisted relationship between two of the heroes from Chronicles: the manipulative, evil mage Raistlin and his twin Caramon, who’s devoted to his brother in an obsessive, self-destructive manner. Two other characters come along for the ride: the carefree kender Tasslehoff and a newcomer to the story, the proud but naïve priestess Crysania. There are a handful of minor characters with point-of-view scenes (Bertrem, Tika, Denubis, etc.), but they mostly serve to either help develop the main characters or give us a viewpoint to watch the main characters interacting. It’s such a delightfully focused reading experience by comparison.

Raistlin is the character around whom the entire plot revolves. He’s learned much in the service of the Queen of Darkness, unlocked the spellbooks of the greatest mage to have ever lived, and plumbed the secrets of the Tower of Palanthas, and now he’s the most powerful wizard in the world by a wide margin. He could take over the world if he thought it was worth doing, but that’s chump stuff to a guy like Raistlin. Instead he has a plan to destroy Takhisis, the dragon goddess who’s the literal embodiment of evil, and take her place — a goal that’s described as so far beyond insane that it sort of wraps around and starts to make sense again. But he can’t do it alone; he needs to manipulate people into helping him with certain aspects of his plan.

This is a dangerous setup for a character. Making him so powerful risks turning him into an unstoppable foe whom the protagonists can’t hope to thwart, and making him the master manipulator behind the scenes of the plot risks stripping all agency from the rest of the characters. Thankfully, the authors thread this needle quite well. Despite his vast magical power, Raistlin isn’t infallible — he has to struggle with his growing attraction to Crysania which threatens to upend his plans, and Tasslehoff’s interference in the plot is something he never could have expected. And it turns out that he’s not as good at manipulating people as he thought, because Caramon is able to surprise him at the end. We only rarely see his composure slip, so when it does we know that it’s serious business.

Raistlin makes an excellent villain because he’s genuinely evil, not just cartoon-villain evil or tragically misguided. He doesn’t hesitate to sacrifice other people’s lives in pursuit of his goals, and his treatment of his twin brother is entirely heartless and unsentimental. Like Caramon, the reader begins the book hoping to see him get redeemed, but by the end of the book one just wants to see him destroyed.

His brother Caramon is the beating heart of the story, since the main theme of the Legends trilogy is him finally growing up and learning how to be a complete person without being unhealthily co-dependent upon his twin. He begins the novel as an alcoholic wreck, and the alcoholism is handled very realistically. His recourse to alcohol was the natural result of how the last trilogy ended — unable to get over his brother’s betrayal and feeling, for the first time in his life, that nobody needs him. The effects, both on him and on his loved ones, are played deadly seriously, with very little “funny drunk” comic relief and lots of focus on the pain it causes his friends and loved ones. Over the course of the novel he hits rock bottom, finds new goals in life, and rids himself of some of his desperate neediness, all in a way that doesn’t feel cheesy or contrived.

Caramon starts the novel with a ridiculously idealized conception of his brother: “Sure, he’s done some bad things, but he’s basically the same kid I grew up protecting, right?” It’s both satisfying and tragic to watch the truth dawn on him over the course of the story: Raistlin is all in for Team Evil, he’s never turning back, and Caramon has nothing to offer him any more. The gradual erosion from “He’ll quit being so evil and come back and live with us!” to “He needs to die” is really well done.

Tasslehoff’s blithe, carefree point of view is still a huge asset to the novel, and his kind-hearted and surprisingly practical mindset makes him the most sympathetic character here. His experiences during the war have fundamentally changed him, making him more responsible and compassionate, which gives him some much-needed depth. Despite not being essential to the plot in this book, he still serves a necessary structural role — we need an outside point of view to watch Caramon’s gradual transformation, and we need a foil for Caramon to interact with. His moments of levity help offset the darkness of the main plot, and his serious emotional moments are heartbreaking.

Another time he misjudged the depth of the water running in the street and found himself being washed down the block at a rapid rate. This was amusing and would have been even more fun if he had been able to breathe.

He’s left in an unsurvivable situation at the end of the novel, left behind by the others at Ground Zero of the Cataclysm and about to be hit by a planet-rearranging meteor. But it’s just a cliffhanger, of course. The authors aren’t going to kill him off here, at the end of the first book in a trilogy. They’ll kill him in 1995 in a way that will alienate the entire fanbase and get retconned almost immediately! Sigh.

That said, I still don’t think that kender kleptomania works as a character trait. The authors portray it as an absent-minded, good-natured sort of thing where the kender responsible has the best of intentions at the time when they pick something up and then forget about it, but the way they rewrite their own reality and convince themselves of whatever they feel like believing feels bizarre and sociopathic.

Crysania, a high-ranking priestess in the newly re-established church of Paladine, is the epitome of Stupid Good. She believes that Paladine, chief god of good, has given her a mission to redeem Raistlin and turn him from evil. (Good luck with that, hon.) But she’s sheltered and naïve, with a child’s understanding of good and evil, and has no idea how to deal with a complicated case like Raistlin. As such, Raistlin has little difficulty convincing her to question her faith, go rogue, and help him reach the Abyss so he can challenge Takhisis. This could have been insufferable, but fortunately the authors spin it so that it doesn’t feel like frustrating stupidity, but rather like the inevitable consequence of her hubris. She’s vain enough to be easily tempted by glory, so proud that she never stops to consider that she might be wrong, and too guileless to recognize Raistlin for the sinister schemer he is because he doesn’t fit her preconception of what “evil” should look like. Her theme over the course of this trilogy will be “hard-won wisdom,” making tragic mistakes and learning valuable lessons from them too late.

The book is populated by many minor characters who feel vivid and interesting: the staff of the bar in Solace, cabals of fractious wizards, the gladiators in Istar, et cetera. They all get names, relationships with the other characters around them, problems that make you empathize with them, and interesting character moments that flesh them out. It’s a good use of a supporting cast, and definitely an improvement over the first trilogy.

This is the first appearance of Dalamar, another long-running fan favourite character in Dragonlance lore. He’s Raistlin’s apprentice, a pathologically ambitious exiled elf who would sacrifice anything for a chance to learn from the most powerful possible teacher on Krynn. He’s been assigned by the Wizard Board of Directors to spy on Raistlin and figure out what he’s up to, but his genuine fanatical devotion to Raistlin gives him an interesting conflict of loyalties. Later books will give him more screen time, but in this book he’s just a colourful minor character who sells how powerful Raistlin has become, gives us a point of view through which we can watch Raistlin at work in his tower, and then hilariously chews the scenery like a B-movie villain at the Conclave meeting.

Plot

It’s obvious from the very beginning how much this trilogy is benefitting from not being tied to a series of Dungeons & Dragons adventures, because the hook that kicks off the story is one that you’d never see in one of TSR’s D&D modules. A few of the Heroes of the Lance arrive in their old hometown of Solace for a brief get-together, only to discover that their former companion Caramon has become a pathetic, bloated alcoholic who’s completely self-destructed after being abandoned by his brother. It’s a problem that can’t be solved by combat or skill checks, and feels like the believable outcome of the way his character was set up in the last trilogy. (A year and a half seems like a pretty ambitious timeline to go from a muscled Adonis to a hideous blubbery drunk, but I’m willing to give the authors a pass on the little details because it makes for great drama.)

We begin this echo of Dragons of Autumn Twilight’s opening with some scenes of Tika, Caramon’s wife, trying to deal with the stress of her friends’ visit. These scenes are fantastic — something is clearly terribly wrong, but the reader isn’t shown what it is yet. Tika’s portrayal will feel familiar to anyone who’s seen what alcoholism does to a family: helpless to improve her situation, blaming herself for Caramon’s problems, ashamed of what her friends will think, angry and lashing out at the people around her. It’s realistic and heartbreaking. But she’s still holding onto the tattered shreds of her self-respect and badassitude, standing up for herself instead of being buried under her tragedy.

Tanis shows up briefly to narrate how the world has changed in the two years since the war ended: people becoming complacent and assuming that everything is over, even though giant armies of draconians, hordes of evil dragons, and their flying citadels survived the war and are presumably still causing problems. That’s some remarkably quick forgetting! But he and Riverwind, who also makes a cameo at the beginning, make great contrasts to Caramon. They’ve both successfully navigated the post-war transition from adventurers to celebrities and politicians, while Caramon doesn’t have any skills he feels needed for aside from “hit things with swords.” The other heroes have stayed involved in trying to heal the scars of the war and keep conflict from breaking out again; Caramon, meanwhile, has become self-absorbed and unable to get over the past.

Despite Tika’s best efforts to keep them apart, Tanis and Riverwind end up seeing Caramon at his worst and are devastated at how far he’s fallen — and so is the reader, who doesn’t know anything more about the situation than they do. The scene where Caramon first appears is a crucial moment, the point where the authors introduce the overarching theme of the trilogy: Caramon’s long, difficult voyage of self-discovery. We start this novel by seeing how far he’s fallen, then spend the rest of the trilogy watching him slowly rebuild himself.

Frankly, this opening is grim as hell. There’s nothing of the Hallmark movie about this redemption story — it’s ugly and honest and deeply, deeply sad.

Crysania has come to Solace with Tanis to get Caramon’s help in redeeming his brother, but is repulsed by what she finds and manages only an insincere, performative kind of compassion for him. It’s good that we got a brief prologue from Crysania’s point of view at the start of the book before we see how cold and unfeeling everyone else perceives her to be; that way, the reader knows that it’s an act she puts on in front of others and doesn’t start with an instant hatred for her. Still, she doesn’t come off well in these scenes — you sort of wish that Tika would slap some basic politeness into her. She ends up heading off to the Tower of Wayreth on her own, without the bodyguard or allies she’d hoped to recruit.

Unfortunately, a gully dwarf shows up in the Inn of the Last Home scenes, and he’s just as bad as you’d expect: another awful mentally handicapped person who gets on his hands and knees and laps up spilled beer like a dog for comic relief. Later, gully dwarves will be described as eating books and using mashed potatoes for a pillow. They’re treated like animals who are just barely smart enough to talk — not only by the characters in-universe, but by the narrator as well. Just… stop it. Forever. We don’t need more of this subhuman mongrel race crap. Bupu gets a dramatic “I am not an animal! I am a human being!” speech later on, but it’s cut off at the knees by the broken caveman English in which it’s delivered and the way she’s been used as comic relief up to that point. Hell, she doesn’t even merit a description — she’s introduced as just “a shapeless bundle of filthy rags.” Everything gully dwarf-related is just one facepalm moment after another, so it’s a huge relief that they’re mostly absent from the second half of the book.

Tasslehoff shows up late towing Bupu, the gully dwarf whom Raistlin befriended in Autumn Twilight and whom Crysania hopes to use to convince the Conclave that Raistlin isn’t irredeemable. He gets to be our camera for watching Tika throw Caramon out, charging him to get his shit together or never return. (You go, girl.) Tas, Caramon, and Bupu set off to pursue Crysania — very slowly, because Caramon has to stop and get shitfaced at every tavern they pass. In the process we get to see that Caramon is a pathetic drunk, not an angry drunk — he wallows in self-pity because he feels powerless to change anything, and his total self-absorption blinds him to the effects of his actions on anyone else. You know an adventure is off to a terrible start when the kender is the most responsible member of the party.

By this point the reader needs a break from all the personal drama, so we spend a chapter watching Kitiara drop in at the Tower of Palanthas for a chat with Raistlin. The Queen of Darkness may be gone, but the forces she’d assembled are not, and Kitiara is planning to continue her war of conquest with or without her patron goddess. There’s not much for her to do in this novel, however; all of this mostly just serves to set up the conflict between Kitiara and her brother during the next two books. Still, I’m a sucker for some good villain-versus-villain conflict, and it’s perfectly in character for Kitiara to interfere in Raistlin’s plans because she can’t bear to be subordinate to anyone, least of all her sickly little brother. We get some necessary exposition about Raistlin’s deicidal plans, and he gets some good character moments where we see what an amoral manipulator he is.

Meanwhile, things are going from bad to worse for Team Crysania. Caramon is pathetic and useless, Bupu is unhappy and continually threatening to leave, and Tasslehoff well and truly loses his patience:

“And maybe Raistlin knew, deep inside, what I’m just beginning to figure out! You only [took care of Raistlin] because it made you feel good! Raistlin didn’t need you — you needed him! You lived his life because you’re too scared to live a life of your own!”

When they finally catch up with Crysania — and she’s none too pleased to have Caramon’s “help” — they’re attacked by Lord Soth and Kitiara’s draconian minions, who are hoping to kill Crysania to prevent Raistlin from using her in his plans. The draconians put in a particularly pitiful showing, getting beaten to death by a lady who’s never been in a fight before and is armed with only a tree branch. If this is what Kitiara is working with, I think Palanthas doesn’t have much to worry about. The unstoppable Lord Soth fares better, of course, nuking Crysania with a power word: kill which would have ended the story then and there if Paladine hadn’t saved her with some divine meddling. She ends up in a state of suspended animation, with her body imperishably preserved and her soul on ice up in heaven, and then Raistlin remotely meddles to ensure that they end up at the Tower of Wayreth.

(As an aside, this entire trilogy could have been short-circuited if Paladine had just let Crysania get killed here. Her soul would go to heaven, Raistlin’s plan would have been foiled, and nobody would have had to do any time travel or similar fuckery. Way to go, gods.)

Meanwhile, we also get some good scenes of Dalamar and Raistlin at home in the Tower of Palanthas. I love the description of the Tower, which is serious Hammer horror movie material: cyclopean furniture, bubbling alchemical equipment, a basement full of misshapen experiments gone wrong. It’s fantastic setting work that really sells how evil Raistlin has become, and yet he gets a chance to demonstrate his fondness for Bupu, showing that he’s not entirely free of sentiment. The long exposition scenes where he explains more about his plans to Dalamar would ordinarily be boring, but the terror of “does Raistlin know I’m a traitorous spy?” from Dalamar’s point of view gives those scenes a necessary frisson of tension.

Caramon has his “hitting rock bottom” moment after he fails to save Crysania during the ambush. He’s still hopeless and fatalistic, so deciding to climb out of his hole isn’t accompanied by cloying optimism — it’s just a recognition that his current path isn’t getting him anywhere, which is the first step on a long journey.

The high muckety-mucks of the Conclave of Wizards are now faced by an insoluble dilemma: what to do with Crysania? Only a super-high-level cleric can restore her, but there aren’t any in the modern day — what with religion only having recently been reintroduced, nobody’s had the time to grind for XP yet. From Dalamar’s report, it’s clear that removing her would thwart Raistlin’s plans, yet killing her is off the table because they’re unable to harm her divinely preserved body. They can’t just hide her in the basement because then Raistlin would come looking for her, and they’re not at all certain that they could win a “Raistlin single-handedly takes on the entire Conclave” battle. Pretty much the only viable option is the one Raistlin knows they’ll have to take: send her back in time to before the Cataclysm, when super-powerful clerics were a dime a dozen, and let them heal her. While I understand the quandary they’re in, I still wish they’d tried a little harder to find an out-of-the-box solution, because it’s frustrating to watch them shrug and say “Let’s just do exactly what the villain wants and hope for the best.”

I’m going to make an effort to not poke holes in the time-travel aspects of the plot because time-travel stories are inevitably fraught with paradoxes and what-ifs. The best you can do as an author is to establish the rules of how time travel works in your universe up front, stick to them, and try not to call attention to the unavoidable contradictions. As a reader you have to extend the authors some courtesy, refrain from asking “But why didn’t they just do X?”, and try to enjoy yourself. The rules of how time travel works (only kender, gnomes, and dwarves, not being part of the gods’ original creation, can alter the future if they’re sent back in time) are established during a great scene where Par-Salian, head of the Conclave of Wizards, gives a presentation to his fellows using a magical overhead projector (I shit you not), shortly before they become relevant.

I appreciate that the magic in the Tower scenes feels much less like Dungeons & Dragons tabletop material and much more like the over-the-top drama of classic sword-and-sorcery stories:

Par-Salian cried out now with such a loud voice that the very stones of the chamber themselves began to answer in a chorus of voices that rose from the depths of the ground.

You may have noticed from past reviews that I’m not a fan of authors using free-form magic, but what specifically annoys me is when they use it to resolve plot problems. When you’re dealing with plot-device-level magic like this, stuff that’s meant to set up the next story beat or to add wonder and mystery to the setting, I’m all in favour of authors getting creative and going off-script.

The upshot of all this is that everyone ends up back in time, and the second half of the book takes place in Istar shortly before it’s destroyed by the Cataclysm. Caramon is sent back in time with Crysania’s body and a magical time-travelling device that will supposedly allow them to get back home once she’s all better. Tasslehoff hitches a ride, much to everyone’s horror — humans aren’t able to change the future by time travelling, but kender are, so Tas is a wrench in everyone’s plans. Raistlin sends himself back to around the same time to meet the archmage Fistandantilus, whose future self has been time-sharing inside Raistlin’s body for the last several years, and usurp him. Fistandantilus is an odd character: he plays a pivotal role in all of these books, possessing Raistlin and granting him supercharged magical power, but he’s never actually appeared on screen. By the time Caramon & Co. arrive in the past, Raistlin has already learned all of past-Fistandantilus’ secrets, killed him, and taken his place in the Kingpriest’s court, creating an “I’m my own grandpa” type of stable time loop.

Istar makes for a great setting. Aspects of its culture are recognizable from what we know about the setting’s present, but it’s both more grand and more corrupt in every way. The priesthood of Paladine effectively runs the entire continent, so there’s none of the political anarchy that we saw from Chronicles, and they’re such a racist, genocidal bunch of assholes that you want to cheer for the Cataclysm to kill them all. Moreover, I appreciate that Istar doesn’t feel like fantasy Rome. It would have been so easy to lean on lazy “Rome as placeholder for a fallen empire” tropes to flesh out the setting, but aside from the gladiatorial combat there aren’t really any obvious parallels. Instead, the ever-present influence of the theocracy on Istarian society is demonstrated in many small ways. The Kingpriest is much more than just an emperor or a figurehead — he’s more of a messiah figure, really.

And speaking of gladiatorial combat, Caramon gets arrested on arrival, sold into slavery, and assigned to the arena as a fighter. [2] He spends the next several months in a state of enforced sobriety, forced to do gruelling exercises and weapons training that get him back into fighting shape. The gladiatorial combat league, which turns out to be a pro-wrestling style “fake fighting” thing where nobody is supposed to get hurt for real, is a great touch. Of course an ostensibly good-aligned empire would still need bread and circuses, so having the gladiatorial equivalent of WWE replace the actual blood sports makes a lot of sense. The authors do a marvellous job of selling the pageantry of the arena: the Death Pits, the Golden Spike, the crowd-pleasing theatrics. You start to feel that it’s a little bit safe and silly, which makes the shock of a sudden and unexpected death much greater. (Also, one of the important characters there is a sympathetically portrayed Black man, which reminds me how depressing it is that the Forgotten Realms are so far behind Dragonlance in terms of diversity.)

The Istar chapters are mostly intrigue. What’s the deal with the mysterious Fistandantilus? Can everyone escape the impending utter destruction of Istar? Will Tasslehoff’s presence cause events to play out differently? What’s with the conniving bastards surrounding the Kingpriest? How will Caramon escape from his enslavement? Will Crysania succumb to Raistlin’s temptation? Throughout all this, Raistlin demonstrates how evil he is in a way that finally opens Caramon’s eyes to what his brother has become. There are moments of action, but most of it is spent on people talking to each other — and that works just fine, since the stakes are so high and the characters are so well-developed.

I still don’t buy the gods’ “rocks fall, everyone dies” solution to the Kingpriest problem — it didn’t make sense in Chronicles and it makes even less sense now. The warnings and portents sent by the gods are weird meteorological phenomena and natural disasters, not someone saying, “Hey, don’t do this or we’ll kill you,” so I’m not sure how the Kingpriest and his ministers were supposed to puzzle that out. The Kingpriest’s interpretation of these events (“It’s the forces of evil trying to destroy me!”) isn’t unreasonable because there’s no attribution to any of these omens, nor any obvious message. It’s just a series of bad things happening for no clear reason, so millions of lives might have been saved if the gods had done a less crap job of sending omens.

That said, the Cataclysm makes an extraordinarily good climax for the book. The knowledge that everyone and everything we see in the Istar section of the book will soon be obliterated by a terrific disaster makes that entire half of the book feel tragic, and the slow buildup to the catastrophe adds plenty of tension. The Cataclysm itself is appropriately apocalyptic; you know that the main characters won’t die, since this is only book one of a trilogy, but it still makes for an excellent spectacle. In the end, we’re left with a cliffhanger that leads directly into the next book, so I feel sorry for the poor bastards in 1986 who had to wait months for the next volume to be published.

Themes

There’s the obvious theme of Caramon’s gradual self-discovery and character growth, which will run throughout all three books and which we’ll talk more about later. But this book in particular tackles a difficult moral quandary in the Istar sections: Can you enforce goodness? The authors come down hard on the side of “no,” showing how the inevitable outcome of such a regime would be effectively fascism. The theocracy of Istar claims to embody the highest ideals of goodness and compassion, yet commit genocide and enslave people in service of making a better world:

“Isn’t it logical, therefore,” said the Kingpriest to his ministers on the day he made the official pronouncement, “that slavery is not only the answer to the problem of overcrowding in our prisons but is a most kind and beneficent way of dealing with these poor people, whose only crime is that they have been caught in a web of poverty from which they cannot escape?”

It demonstrates that, no matter the ostensible ideals of the government, the most manipulative and hypocritical people will always rise to the top. The best the gods can do is give people free will and try to minimize the fallout from their inevitable mistakes — which means that the gods of Good are really the gods of Neutrality, since they’re trying to restore the balance, and who knows what the hell the gods of Neutrality are for. But there’s so much that’s fundamentally broken about the morality system in Dragonlance that there’s no real point to nitpicking it, so I’ll just leave it at that.

Unusually for a TSR novel, the romance between Raistlin and Crysania gets lots of time and attention here. It’s a great change of pace — romance is a genre that rarely gets used in these novels outside of the occasional subplot — but I don’t much like the way it’s executed. Relationships in Weis and Hickman’s novels seem to always be told from the male perspective. The things the men angst about are usually privileged nonsense like “which hot lady do I pick” or “oh no, my crush turned out to be a super rad dragon girl” that are harder to have empathy for; meanwhile, it’s always the women who have to sacrifice things they care about for love. The women don’t have agency in their romance, since they’re always pursued or drawn to a relationship by destiny rather than choosing it for themselves, and the only counterexample who takes charge of her relationship situation is super evil. It’s not a great look. (Also, there are zero women in Dragonlance who are not described as 9/10 incredibly hot, which feels like pandering to the teenage demographic.)

Crysania’s romance starts off as another instance of the standard pattern. In her first scene the authors basically describe her as “she’d be beautiful if she wore makeup,” which is not a great message. She’s magnetically drawn to Raistlin from the instant their eyes meet, mesmerized by how awesome he is rather than being drawn to him for a clearly established reason. When did Raistlin go from being the weird guy that nobody likes to an irresistibly charming Svengali? The extremely straitlaced Crysania’s instant attraction to him is a bit too sudden to make sense, so it feels like the hand of the author shoving them together rather than the inevitable outcome of their respective personalities. Being tempted by evil is something that should be built up slowly, gradually eroding the character’s willpower — it shouldn’t just hit the character like a truck.

That said, the authors do a better job of it in the second half of the book once the action moves to Istar. Raistlin uses Crysania’s horror at the hypocritical pre-Cataclysm theocracy to erode her faith and get her on board with his “let’s challenge the gods” plan, which means that there’s less “spellbound by his alluring gaze” crap and more arguments about morality and ethics. He has to actually work at it using all of his skill in manipulation and deceit, and it feels plausible for Raistlin to run rings around Crysania in debates because she’s too sheltered and naïve to realize how outmatched she is. We also get some good scenes from Raistlin’s point of view which demonstrate that, far from being a passionless chessmaster, he’s actually struggling with his unexpected attraction to her. This is all setup for the next book, since their relationship status by the end of this one can be summed up as “it’s complicated,” but it’s narratively stronger and more in character than their first couple of interactions.

Writing

The writing is generally quite good. Sometimes the omniscient narrator maladroitly tells the reader details that the characters couldn’t know. Sometimes sentences are awkwardly glued together with comma splices, or the narration is marred by occasional exclamations. Sometimes the authors overuse their favourite adjectives, like Crysania’s “marble skin” or Raistlin’s “feverish gaze.” But these are minor nitpicks next to all the things I liked about it. The character moments are affecting and not overly sentimental, and nothing seems self-indulgent or unnecessary. The descriptions are vivid and engage all the senses. The pacing is on point, slowly ramping up the tension from painful conversations in a sleepy little town to escaping from a continent-destroying catastrophe. The authors’ improvement in their craft is really quite noticeable.

I’ve never praised a TSR novel for its appearance or layout before, but the beautifully illustrated initial capitals that begin each chapter make me very happy. I wish they’d bothered to do that with more of their books. (The Chronicles books had little black-and-white illustrations at the start of each chapter, but the scratchy, handmade style of these capitals, drawn by frequent TSR illustrator Valerie Valusek, feels more evocative and manuscript-like to me.)

Conclusion

Grade: A

It’s an easy A. The character work is on point throughout, the plot is twisty and fun, and the authors nail the dramatic scenes without veering into melodrama or sappiness. It’s not without its flaws, but the issues are so slight compared to the things I enjoyed that I can’t much be bothered by them. It was difficult to force myself to take my time and carefully write this review instead of plunging straight into the next book.

And now for a completely unrelated plug! If you have any interest in the history of TSR and Dungeons & Dragons, I’d quite recommend the podcast When We Were Wizards, which I’ve been listening to lately and enjoying the hell out of. I’m no stranger to the topic of TSR history, but it adds a whole new dimension to hear the actual people involved discussing it in their own voices. It really drives home the core theme of five decades of D&D: that it’s an idea so good that even a horde of maliciously incompetent people trying their hardest haven’t yet managed to destroy it.

Footnotes

[1] Frankly, “Legends” always seemed like a strange name for the trilogy, given that this series is focused largely on character growth and interpersonal relationships rather than big mythic conflicts. Marketing decision, maybe? It is a mystery.

[2] It’s a plot point that Caramon is arrested on suspicion of having raped Crysania, but the authors are clearly not allowed to use the word “rape” in any way, so everything is done via insinuations and innuendos. It feels very, very awkward and I wish they’d just not tried.

More Christmas in July from our esteemed host. And with that…

-In Spring Dawning, Riverwind mentions that he’d never trust Raistlin. Meanwhile, the Lost Chronicles’ Dragons Of The Dwarven Depths has him be one of the first to recognize that Caramon needs to realize that Raistlin can take care of himself. Given what Raistlin eventually does and Caramon’s own character arc, Riverwind comes across to me as one of the most far-sighted characters in the entire series. What’s even more impressive is that he figured these things out before most of the rest of the party despite not knowing the Majere brothers nearly as long as them.

-I’m surprised our esteemed host didn’t mention Tas mumbling to himself about quitting his wanderlust and moving back in with his parents to become a homebody. That’s the epitome of “OOC Is Serious Business”, and reinforces just how bad things have become during the draconian fight scene.

-I’m still kind of puzzled as to why the Conclave would send a Caramon who seems well past his prime to the past as their main hope to stop Raistlin, given that he can barely stand up straight. And as heartless as it is, leaving Crysania in a coma would pretty much ruin Raistlin’s plans.

-I don’t recall how much screen time Fistandantilus actually gets in this novel, but I distinctly recall how the authors emphasized his creaking bones and withered flesh, implying that he’d all but become a lich. IMO, that’s W&H’s best use of evocative language and showing rather than telling in this book.

-Others have mentioned how Tracy Hickman’s Mormonism shaped the early part of the Chronicles, namely how the First Nations-inspired Goldmoon would find the Disks of Mishakal that would stand in for the golden plates Joseph Smith read. I agree with everybody who says that he mostly fumbled that. However, I think he explores theology and corruption much better in this series-if the Raistlin scenes were written by Weis, the scenes involving Istar’s corruption were almost certainly written by Hickman.

Remember, these books were written at the height of the “Satanic Panic”, when Pat Pulling, Jack Chick and their ilk were trying to depict D&D play as devil worship. Having a guy who was heavily involved in his church like Hickman probably would’ve been shocking to the D&D critics, and Hickman himself described some of D&D’s critics as “well-meaning but misguided.” I wonder how much of a role he had in thwarting the Pullings and Chicks of the world.

-I’ve gotten to Divine Hammer in the Kingpriest Trilogy, and those books are incredibly evocative in describing how fabulously wealthy Istar is, with previous gems and metals used as casually as porcelain or chrome would be. Meanwhile, people on the outskirts of the empire were living hardscrabble lives and dying of plague. It’s easy to see why Brother Beldyn (who changed his name to Beldinas after becoming the final Kingpriest) got so many of those people to follow him against Kingpriest Kurnos, who’d made deals with Fistandantilus to gain and keep his throne.

Of course, while Beldyn starts as a kind, compassionate healer, there are already signs of his fanaticism and dislike of the Balance. As Kingpriest, he does nothing to spread Istar’s wealth and goes even further than Kurnos ever did. It, and the Twins trilogy in general, reinforce what I mentioned in a previous review about how righteousness risks turning to self-righteousness. The self-righteous are so convinced of their own goodness that they handwave any dubious activities they perform to achieve their goals. It’s all too real today, whether French revolutionaries guillotining people by the hundreds in the 18th century or activists engaging in social media pile-ons and doxxing today.

Don’t expect another post for a month or so! I’ve got a lot going on this summer.

Fistandantilus gets zero screen time in this novel. By the time Caramon arrives in the past, he’s already been killed and replaced. The scene you’re thinking of is from the beginning of War of the Twins, when the Tower ghosts make Raistlin relive his memories of defeating Fistandantilus.

Leaving Crysania in a coma would definitely thwart Raistlin’s plans, but the question is “where do you hide the body?” Because if Crysania disappeared, the leaders of the Conclave knew that Raistlin would come looking for her and destroy the entire Tower of Wayreth if he had to. They clearly don’t fancy their chances of survival if it comes to a straight-up fight:

So they figured their best bet was to send her back and hope that she either disappears during the Rapture or gets atomized by the Cataclysm. Meanwhile, Caramon wasn’t sent back to stop Raistlin, but to learn the truth about Raistlin and then return alone. Par-Salian was trying to help him.

Why is it that in the last book you called Laurana an idiot for trusting Kitiara, but in this book Raistlin makes the exact same mistake, without a word of criticism from you for him? If trusting Kitiara is as foolish as you previously argued then it seems like intellectual honesty would necessitate you saying something like, “only a complete dumbass, an absolute gibbering moron, would gamble the outcome of his plan on a Dragon Highlord being honest and keeping her word. So of course Raistlin walks right into it. Sigh!” right about now.

Indeed I would contend that Raistlin’s decision to trust Kitiara here is far more foolish and illogical than Laurana’s decision to trust Kitiara in the last book was, since Laurana at least had a logical reason for believing Kitiara was an honorable enemy that didn’t want to harm her based on her prior encounter with Kitiara, whereas Raistlin knows full well that Kitiara is a dishonorable person. (If nothing else just the fact that Kitiara betrayed Laurana in such a despicable manner, should be all that Raistlin needed to know that Kitiara can not be trusted.)

I also don’t understand your argument that the good women in Dragonlance lack agency when it comes to romance. Laurana at least certainly had full agency in that area as she didn’t just sit in an ivory tower waiting for her prince to come but instead decided who it was she wanted to be with and then went after him with her defying the racism and classism of her people and family to be with the person she loved. (And equally important, she also proved fully willing to reject Tanis when it appeared that she couldn’t trust him.) That Laurana’s choice was to be in a monogamous relationship doesn’t make it any less valid or any less her choice born of her agency.

My dude, you have written around 3,600 words worth of comments on here so far, and not one of them has not been all about Laurana. I get having a favourite character, but when taken to this degree it’s starting to weird me out. Are there no other aspects of these books that would be interesting to talk about? I am happy to entertain disagreements and discussions, but not if they become uncivil — please assume a certain amount of good faith on my part and the parts of the other commenters, and please be less free with accusations of intellectual dishonesty. This is not an exhaustive scholarly review of an objective topic; it is a collection of my subjective impressions of a story.

I think you misunderstood my point about agency. Laurana has agency as a character in general, definitely — what I mean is that she doesn’t have agency to choose her romantic relationship. Tanis has been the love of her life since long before the first book began, so she doesn’t make a choice to be in love with him. (Your point about her being willing to reject him is well made, though.) Same with Silvara and Goldmoon, who don’t get a choice about whom they love — they have instant “love at first sight” starts to their relationships that feel like destiny/the authors shoving them together. Furthermore, Laurana has to make huge sacrifices — her place among her people, the respect of her family — and Tanis doesn’t have to sacrifice anything. Similarly, Silvara and Goldmoon make huge sacrifices for their relationships, but their partners Gilthanas and Riverwind don’t. Crysania is in the same position — she risks everything for a guy whom she barely knows and who treats her like a useful tool. I wish that were not the dominant paradigm for relationships in the Dragonlance books, but it seems to be the norm for all female protagonists except Tika.

only a complete dumbass, an absolute gibbering moron, would gamble the outcome of his plan on a Dragon Highlord being honest and keeping her word. So of course Raistlin walks right into it.

It’s been a while since I read this book, so I had to pull my copy out of cold storage and take a look, but I don’t think there’s nearly as much comparability between the scenes as you suggest. The whole prisoner-swap thing with Laurana was a very specific agreement, one with an obvious trap (only Laurana can come, no negotiating by subordinates!) where a straightforward and obvious betrayal by Kitiara (by capturing the small prisoner-swap force) would upset everything. The Raistlin-Kitiara negotiations are a lot more amorphous: there’s no actual plan laid down for on party to renege on, just a sounding-out of potential alliance. Raistlin tips his hand a bit far in ways which Kitiara can take advantage of (revealing Crysania’s vital role in his plan), but there’s a reasonable read that that’s information he would need to share in order for his plan to seem remotely credible at all.

At the end of their negotiations, it’s not clear Raistlin does trust Kitiara, or that he’s adapting his plans based on any sort of presumption she’s acting in good faith. He doesn’t foresee the particular way she chooses to oppose him, but unlike in the Laurana-Kitiara deal, the point where the deal is brittle isn’t obvious. That her particular attempted opposition would be a strike directly at Crysania isn’t self-evident, whereas in the prisoner-swap agreement, the answer to the question “if Kitiara’s not acting in good faith, what would she do?” is pretty obvious.

Really, if you want to read this as an act of gullibility, you have to go all the way back to “inviting Kitiara to visit at all” and “sharing some details of his plan”, which seems a lot less gullible than “making a very specific arrangement and expecting her to play fair”.

@Jake: Hard disagree. Raistlin explained Crysania’s role in his plan to Kitiara and then emphasized just how important Crysania was to his plan just in case Kitiara hadn’t figured it out on her own.

“Now you understand,” Raistlin smiled in satisfaction and resumed his seat once more. “Now you see the importance of this Revered Daughter of Paladine.”

-Time of the Twins, Book I, Chapter 5

That’s not simply “sharing some details of the plan.” That’s telling Kitiara exactly what she needs to do to defeat the plan. And based on Raistlin himself identifying Crysania as the critical asset/failure point for his plan, it should have been blindly obvious to him that if Kitiara wanted to betray him, she would do so by striking at Crysania. The answer to “if Kitiara’s not acting in good faith, what would she do” is thus every bit as obvious in this situation as it was in the trap against Laurana, since Raistlin literally told Kitiara where his critical vulnerability was.

As for the idea that Raistlin didn’t trust Kitiara after their negotiations, if that was the case then why did Raistlin take absolutely no precautions to safeguard Crysania from an attack? And why was he surprised and angry when he found out that Kitiara had betrayed him? He was obviously caught completely flat footed by Kitiara’s betrayal which shows that he did trust Kitiara.

As for the idea that Raistlin needed to tell Kitiara about Crysania to make his plan seem credible, how do you figure that? Kitiara isn’t a trained wizard, so it’s not as though she is going to know what it takes to open a portal to the Abyss. He could tell her literally anything about how he’s going to open the Portal, and she would believe him. (Remember Kitiara just saw her most powerful agent, a being of immense magical power, bow to Raistlin as his superior. I don’t think she is doubting Raistlin’s magical abilities at this point.)

And why does Raistlin need to sell Kitiara on his plan anyway? Why pursue an alliance with her at all? She brings nothing to the table. She’s obviously not a trustworthy ally given her history of treachery. Nor can Raistlin rely on his family connection to her to keep her from betraying him. (Remember in the last book she drove the ship Raistlin was on into the Maelstrom even after knowing Raistlin and Caramon were on it, and Raistlin knows that she did this, so he knows she is perfectly willing to kill him for her own gain.) And seriously what use is Kitiara going to be to him in fighting against a god anyway? Raistlin choosing to tell Kitiara about his plan was not part of any rational strategic calculation. It was a purely emotional reaction from him. (Basically he’s reverting to the little boy who wants to impress his older sister/surrogate mother figure with how clever and powerful he is and because of that emotional need for validation, he put himself in a position where Kitiara could betray him and destroy his whole plan.)

So again Raistlin’s mistake was very similar to Laurana’s. They both made the same error in judgment (trusting Kitiara.) Both of their mistakes were born of their emotions. (Laurana wanting to care for the man she loved when she thought he was dying and asking for her, Raistlin wanting validation from his older sister.) And in both cases their mistakes left them vulnerable to a devastating defeat.

The only differences in the situations are that Laurana at least had an understandable and logical reason for thinking that Kitiara was an honorable enemy who did not want to harm her and thus would respect a truce while Raistlin had no reason to believe that Kitiara was honorable or that she wasn’t perfectly willing to kill him, Laurana had to make her decision while under immense stress and time pressure, whereas Raistlin was under no time pressure or stress at all when making his decision to trust Kitiara (which should have made it a lot easier for Raistlin to come to the “correct” decision), and of course Laurana didn’t tell Kitiara exactly how to defeat her like Raistlin did.

Laurana’s character and story is by far the part of the book I find the most interesting. Obviously any comments I make on the book are going to focus on the part’s that I find the most interesting. Some of your comments about Laurana are also the parts of your commentary where I have disagreements with you and thus those areas seem like the areas most fruitful for discussion. There’s plenty that you have said in your reviews that I agree with (in particular I fully agree with your points about the gods of good, and how Paladine acts much more like a god of neutrality), but I just don’t see much value in commenting on topics, where all I really have to say is that I agree with you (or to basically repeat the points you already made), so my comments are naturally going to focus on the topics that both interest me and where I feel I have something to add other than just agreeing with you, and so far that has meant just talking about Laurana.

Otherwise, if you felt my post was a personal attack then I apologize. That was certainly not my intent. I do think though that it is valid to point out the disparity in how you criticized Laurana compared to the lack of any criticism of Raistlin for making the exact same mistake. One of the things that I’ve always found telling about the Trap plotline is how Laurana gets roasted by so many fans for conduct of a type that doesn’t ever seem to get criticized when it is done by a male protagonist. (Just think about Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back or Harry Potter in The Order of the Phoenix for instance. They essentially make the exact same mistake Laurana does in Spring Dawning, but don’t receive even a tenth of the criticism Laurana gets.) And I’m not saying that these different reactions are born out of bad faith or deliberate sexism, but they do suggest an unconscious bias in the speculative fiction fan community (if not in society at large) where woman are judged much more harshly for acting on their feelings than man are, and that disparity needs to be addressed when it appears because how else are we going to dispel such biases if we can’t talk about them?

Otherwise I’m not sure I agree that Laurana didn’t get to choose to be in love with Tanis. Part of her story in the Chronicles is learning that Tanis is not the idealized perfect man that she once believed him to be but instead makes mistakes and has real flaws. Thus it could be said that while Laurana started off the series in love with an idealized version of Tanis, she ended up choosing to be in love with the real Tanis.

As for Gilthanas and Silvara, doesn’t their relationship actually subvert the love at first sight trope, since their relationship falls apart after two days due to them not knowing each other and thus having no foundation to hold the relationship together once it hits its first rough patch.

As for the male characters not having to make sacrifices for their loves, I’m not sure I agree with that either:

Tanis was willing to sacrifice his freedom and then his life to protect Laurana.

Riverwind left his home and quested for ten years to prove himself worthy of Goldmoon. (Admittedly, this all happened prior to the start of the book, but then Goldmoon’s sacrifice for Riverwind also happens as part of the backstory.)

And while it’s true that Gilthanas didn’t make any real sacrifice for Silvara, I’m not seeing that she made any sacrifice for him either. (Their relationship doesn’t appear to have been based on anything other than physical attraction, so it’s not surprising that neither character was willing to make true sacrifices for the other.)

Your right about Crysania’s relationship with Raistlin but that is explicitly portrayed as an abusive relationship, so I’m not sure its useful to compare it to the other relationships.

One of the things that I’ve always found telling about the Trap plotline is how Laurana gets roasted by so many fans for conduct of a type that doesn’t ever seem to get criticized when it is done by a male protagonist.

I don’t think sexism particularly comes into it here. The thing about the trap plotline is that I don’t blame Laurana for it — I blame the authors. They set up a character who’s grown up a lot, taken on lots of responsibility, is always trying to do the right thing to help as many people as possible, and cares deeply about saving the world. And then the authors, in order to conveniently put all the pieces in place for the conclusion, had her act in a way that didn’t jive with the description I just gave.

You mention Luke Skywalker as a counterexample. In Empire we see how he’s constantly failing throughout his training because he’s impetuous and impatient, and then his low point is his impatience and fear for his friends leading him to fly away and get his ass kicked. It’s thematically appropriate for that character to do something rash and unwise because he’s spent the entire movie being rash and unwise. Whereas with Laurana, up until that point, “rash” and “unwise” are two words that I wouldn’t consider using to describe her — especially after she’s fundamentally changed by her experiences at the High Clerist’s Tower — so it doesn’t feel to me like a mistake that fits her character’s theme. (The only thing she ever did that might be characterized as rash was running away after Tanis, but her life in Qualinost seemed stifling and infantilizing and I don’t blame her for wanting to leave.) Rather, it feels like the authors dropped the ball, and that knocks me out of my suspension of disbelief and makes me aware of the artifice.

As for why I complain about this with Laurana but not with Raistlin, I think that it’s because, like Luke Skywalker, Raistlin making a similar mistake fits his character better. He’s supremely overconfident, and one of the big themes of the Legends trilogy that will become apparent at the end is that his confidence is misplaced and he’s trapped himself in a corner that he can’t magic himself out of. I can definitely believe that he would explain his plan to Kitiara because he doesn’t think that she’s capable of opposing him, so it’s a mistake on the character’s part and not the authors’.

I would dispute that Laurana wasn’t rash prior to the trap scene. Remember this is the lady who

-rushed forward to protect Sturm’s body from Cyan Bloodbane (the second biggest evil dragon on all of Krynn) in the Dream. (Yes, it was a dream, and she was in no real danger, but Laurana didn’t know it was a dream at the time, so I think it still counts);

-unilaterally decided to reveal the Dragon Orb to the Silvanesti (and even jumped right between them and the party when the two sides were about to throw down);

-risked using a Dragon Orb despite only having minimal knowledge of how to use it;

-rushed forward to protect Sturm’s body for real at the High Clerist’s Tower (despite being alone, exhausted, and knowing that in the magical dream she was killed after doing the exact same thing.)

All of those actions were objectively rash (as well as incredibly heroic) and could have blown up in Laurana’s face just as bad as the trap did. The only real difference between those actions and the trap situation (which also has Laurana doing something that was arguably rash but very heroic), is that in those situations taking a risk worked out for Laurana while in the trap situation it didn’t. But judging a decision merely by whether it worked out or not is result-oriented thinking which is usually considered a logical fallacy. Laurana’s underlying thinking (I’m going to face danger to protect the world/someone I care about) was exactly the same in all those situations.

And indeed that’s a big part of why I like Laurana so much as a character, the fact that she is very brave but also doesn’t seem to truly believe that bad things can happen to her (a fault very common to young people who tend to think they are invincible) and this causes her to take risky actions (most of which work out for her because she is very gifted and capable, but anyone that takes a lot of risky actions is eventually going to push their luck a little too far and get burned.) It’s a quality/flaw in her that is very believable given her age, sheltered upbringing, and that fact that she usually does succeed at what she attempts and thus it helps make her feel like a real person while also helping to explain both how she became such an admired, inspiring figure and how she ended up falling for Kitiara’s trap.

I would also disagree that Laurana wanting to help Tanis in the trap situation was inconsistent with her growth arc. Yes, she had a responsibility to her army, but didn’t she also have a responsibility to Tanis (not just as the man she loved but also as the man who had saved her life in Tarsis and who had led the mission that saved her people from genocide)? And since in that moment Laurana’s army appeared to be perfectly safe (it was fully supplied in a friendly, walled port city (pretty much the toughest kind of location to besiege or storm), with no significant enemy forces nearby (even Kitiara admitted she would need a week to get a force together to march on Kalaman) and was so secure that it had literally spent the previous day partying) I can’t really fault her for thinking that for that one moment at least Tanis needed her more than the army did and acting accordingly. Like Captain Kirk said, “sometimes the needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many.”

Anyway, your point about feeling that Laurana’s decision was out of character for her while Raistlin and Luke’s decisions weren’t, is well taken even if I disagree that it was out of character for Laurana. I guess what bothered about your initial comments were the insults thrown at Laurana. It’s one thing to say that you don’t believe the character’s actions seem in-character for them, that’s a fair criticism of the writing, but when you (or others) start insulting the character directly then I hope you can understand why, even if that was not your intent, it might come across like you are judging the character rather than the writing. And while both the question of whether a character’s action male sense for the character, and the question of whether a character’s action make sense, are perfectly valid topics for debate, I don’t think I am being unreasonable by saying that in any discussion of the later it’s not right to hold Laurana to a harsher standard than Raistlin or Luke.)

I would like to thank again our host for his remarkable work! His reviews are so vivid with details that I actually decided to pick up again “Time of the Twins” and give it a re-read of my own. Whereas I read the “Chronicles” at least 3-4 times (you know, the “first love” of my teenage me), I read the “Legends” only once and really long time ago.

From the first few chapters, the concept of the passing of time seems very weird. Crysania is described as somehow “middle-aged” (or at least someone whom was pretty but is now past is prime). She is also described as a young woman when she first met Elistan, implying she is young no more. However, only two years have passed since. The same can be said for Caramon, Tanis, Tika and Riverwind: the way their meeting is described seems like they have been separated for many more years, also from how different they appear (how could Caramon which returned to Solace and was busy rebuilding it for the first period become alchool-addicted in such a “short” period of time?) . It is also pretty unbelievable that the citizens of Solace have forgotten the war in only two years and with the Dragonarimes still around! I don’t know why Weis and Hickman decided to set the Legends trilogy so shortly after the Chronicles: maybe if they had moved it a bit further in the future some of the said oddities would have been less evident… by maybe I’m missing something…

No, I think you’re quite right. It feels like more than two years have passed — Elistan apparently built a thriving church in Palanthas in like, a year? Caramon goes from bodybuilder to derelict in a year and a half. In two years, Riverwind has united all of the Plains tribes and become their leader, and the dragonarmies have done… nothing? It’s not clear.

I don’t necessarily think it’s that strange that these things all happened so quickly. IIRC, Tika notes that Caramon briefly felt useful when he was helping to defend and rebuild Solace, but without Raistlin his life pretty much fell apart and he turned into a slovenly drunk. That kind of emotional loss, probably on the scale of seeing a loved one die, can completely upend someone’s life and make them turn to substance abuse both in the real world and in Krynn.

Meanwhile, Elistan’s building a church in Palanthas isn’t surprising either. He all but disappears from the Chronicles narrative after Dragons Of Winter Night, so he may well have been setting up the foundations of Paladine’s new church even before the War officially ended. Certainly he would’ve helped spread the knowledge of the good gods to peoples like the Solamnics. And when the forces of good start receiving actual, genuine healing spells to even the odds against the Dragonarmies, that’s the kind of publicity you can’t buy!

And the Plainsfolk reuniting under Riverwind’s and Goldmoon’s leadership makes sense to me given that they’re renowned as some of the heroes who saved all of Ansalon and the governance of a lot of the old nations was shattered by Verminaard’s invasion. And if you want to play up the comparison to the real First Nations, the Iroquois and the Blackfoot Confederacies both involved smaller nations uniting for shared interests or against common threats. Many real-life First Nations people have important bonds with the lands they call home, so it’s not surprising that many of the Plainsfolk would want to return home after the War of the Lance is mostly over. There’s still dissent and disagreement among them, as Riverwind mentions when he explains why he can’t escort Crysania and someone else needs to do it. There was plenty of conflict among the old nations too-in Riverwind The Plainsman, Riverwind and his companion Catchflea recall a violent civil war among the Que-Shu over whether Arrowthorn (Goldmoon’s father) or his rival Oakheart should be the next chieftain. Oakheart was murdered during the conflict, and Arrowthorn only avoided being accused because he was with a large number of witnesses when Oakheart died.

I could have sworn the time skip was at least five years, but nope! Probably there was some executive meddling for some reason, forcing the authors to cut down the time gap.

Nice to see these reviews! I read the Legends books in junior high school and then again 10+ years later. The second time around I remember feeling like the character arcs were just re-set and repeated for book 2, and I’ll be interested to see what your impression is.